BENGHAZI, Libya // Cairo’s military involvement in Libya underlines one of its biggest fears: that Islamist militants from across the border will join ranks Egypt’s home-grown militants.

As fighting continued for a third day in Benghazi, where at least 14 people were killed on Friday in fighting between armed youths and Islamist militias, analysts warned that Cairo’s foray into the fighting in Libya could deepen the turmoil there.

Residents have reported Egyptian warplanes have been pounding Islamist militia positions in Benghazi.

Egyptian and Libyan officials have denied Egypt was carrying out airstrikes, while the United States, which maintains a naval force in the Mediterranean that includes surveillance aircraft, has not confirmed the aerial campaign.

US officials confirmed over the summer that Egypt was carrying out airstrikes against militia positions in and around Tripoli. Egypt has denied involvement.

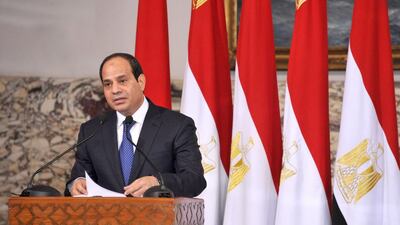

Egyptian military intervention in Libya has long been anticipated since the former army chief Abdel Fattah El Sisi was sworn in as president in June.

Mr El Sisi has striven to restore Egypt’s traditional role as the region’s chief player.

But it has also been dictated by the growing threat from weapons and militants illegally crossing the desert frontier between Libya into Egypt, where Egypt is determined to prevent Egyptian and Libyan militant groups from linking up on its soil.

Egypt has been battling an Islamist insurgency since the ouster last year by Mr El Sisi of the nation’s first freely elected president, the Islamist Mohammed Morsi. Authorities have since cracked down on Mr Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood, killing hundreds of its supporters and jailing thousands.

The post-Morsi violence began in the Sinai Peninsula, long a bastion of dissent and militancy but later spread across much of the country with bombings and assassinations.

Egypt’s involvement in Libya “is bound to exacerbate the fault lines and push the other side towards more militancy”, said Frederic Wehrey, a senior associate in the Middle East Programme at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

“Libya is complex, with a mixture of hard-core jihadi groups, but a lot of those Islamists are into participation in the political process,” said Mr Wehrey.

Jason Pack, a Libya expert at Britain’s Cambridge University, also warned of the complexity of the Libyan conflict, saying Egyptian involvement could have unforeseen consequences.

“Egyptians are making the same mistakes in Libya that the West made in Iraq and Afghanistan,” Mr Pack said. “They support one side over the other. But in Libya the divisions are not between Islamists and non-Islamists. The conflict is very complex.”

Libya is witnessing its worst spasm of violence since Muammar Qaddafi’s regime was overthrown in 2011 by Nato-backed rebels following an eight-month civil war. Militias born in that conflict have since challenged successive governments, which have failed to integrate them into the army and security forces or rein them in, leaving armed militiamen to operate outside state control with impunity.

In June, after Islamist factions fared poorly in parliamentary elections, militias supporting them launched a broad offensive that ended with Libya’s two biggest cities – Tripoli and Benghazi – falling under their control.

The elected parliament and internationally recognised government was forced to move to the eastern city of Tobruk as the militias in Tripoli revived an old Islamist-dominated parliament and formed their own government.

Since Qaddafi’s ouster and the overthrow of Egypt’s long-time ruler, Hosni Mubarak, in Arab Spring uprisings, Egypt has become a major transit route for smuggled arms and militants across the Egyptian-Libyan border. Rockets, anti-aircraft guns, mortars and artillery that flooded Libya during the civil war have found their way to the Sinai and into the hands of the militants fighting army troops and police there.

Since his rise to power, Mr El Sisi has repeatedly warned that the upheaval in Libya poses a serious threat to Egypt’s national security.

Last month, Mr El Sisi blamed the West and Nato for backing the rebels fighting Qaddafi’s forces then withdrawing with the “job incomplete”.

“Weapons should have been collected, the army and security agencies should have been rebuilt, and there should have been help in setting up a democratic system that satisfies all Libyans. That never happened,” he said.

The Egyptian airstrikes were greeted with mixed reactions on the ground in Libya.

“If I were El Sisi, I would do the same,” said former rebel commander Fadallah Haroun, who supports the Libyan army’s Benghazi offensive. Libya’s eastern frontier, he said, is “Egypt’s strategic backyard and it is better to secure it before chaos spills across the border.”

“If you ask people here, they would support Arab involvement to restore stability and stop the daily bloodshed. A lot of blood has been spilt here,” he said.

Mohammed Gaballah, 23, a Benghazi resident, said he opposed foreign involvement.

“I am against turning Libya into a stage for settling scores among international and regional players. This will only increase the proxy war,” he said.

* Associated Press