BEIJING // It was the most unconventional of love stories: the daughter of a South Korean pastor jailed in China for helping North Koreans flee their repressive homeland, and the Chinese interrogator who threatened the pastor with death. It all started in Dec 1999, when Chun Ki-won, the South Korean pastor, helped the first of what became hundreds of North Koreans to safety. At the time, Stalinist North Korea was experiencing its worst food crisis, resulting in the deaths of between one and three million people from famine.

Thousands were making the risky flight across the border into China, where they are considered illegal migrants and if caught, deported back to North Korea to face jail and possible death. Even if they avoided capture, life on the run in China could be unbearable. In the mid 1990s, Mr Chun, at the time a small-scale hotel owner, was in China looking for business opportunities. As he travelled through cities along the border with North Korea he witnessed first hand the desperate plight of North Koreans.

In Tumen, he saw a frozen corpse floating in the river; it was that of a refugee who had died while trying to wade across the river that separates the two countries. In a nearby city, a group of North Korean children, about five years old, were beaten by Chinese police for begging. Later that night, he saw a North Korean woman screaming as she was dragged down a street by a group of men. His Chinese guide explained that "whoever catches her first, can own her".

That sombre experience was a turning point for Mr Chun. After he returned to South Korea, he enrolled in a seminary. When he became a pastor in 1999, at the age of 42, he made it his primary mission to help North Koreans escape. Most North Korean defectors rely on the help of missionaries or commercial brokers running underground railways that organise perilous journeys by train or on foot through the Inner Mongolian desert or south to the borders with Vietnam, Myanmar and South East Asia, with the eventual aim of landing in South Korea.

Many of the brokers are themselves defectors, charging about US$3,000 (Dh11,000) per person. The South Korean Embassy in Beijing estimates there are about 30,000 North Korean refugees hiding in China. In recent years, many have sought refuge in foreign embassies in the Chinese capital, often scaling the missions' walls in dramatic attempts to avoid capture and deportation. It is thought that about 10,000 North Koreans have fled since the mid 1990s, and by 2001, Mr Chun had helped 250 of them.

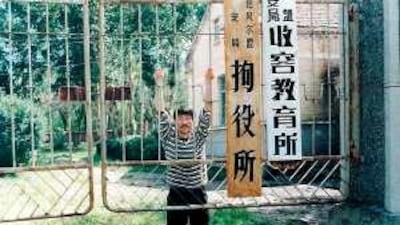

But then, on Dec 29 of that year, as he led a group of 12 defectors across the China-Mongolian border, he was arrested. He was held in prison in China for eight months, during which time he was threatened with the death penalty unless he revealed who was the real mastermind helping the defectors to escape. For the eight months he was detained, he was asked daily who he took orders from, and each time, Mr Chun replied that he answered only to his own conscience and to God.

Then, one of the interrogators approached him while the other two were away and again asked the same question: "Who's behind all this?" Mr Chun recalled. When he repeated the same answer, the guard asked: "Do all people who go to church do this, like you?" A few days later, the same guard asked if someone like him could read the bible. Mr Chun was worried. He thought the guard might be trying to trap him. In atheist China, missionary activity is illegal.

But still, he replied that it was possible. Mr Chun was eventually released from jail with the help of international human rights organisations and petitions from US legislators and deported back to South Korea. Although he was banned from China until 2012, he has remained active in helping North Koreans to flee. By Oct 2007, about 500 people had escaped with the help of Mr Chun's group. A few months after his return to Seoul, Mr Chun received a phone call from China. It was the interrogator who had asked about the bible. "He was thinking about coming to Seoul for travel. I told him to come over and stay at my home," he said.

"The second day of his arrival was Sunday. I needed to go to church. But I didn't ask him to go with me because I knew he was a Communist Party member and worked for the Chinese government." So it was a surprise, he said, when the man asked to join him, something Mr Chun put down to curiosity. "There were about 3,000 people in the church and they were really surprised to see a Chinese man who had prosecuted me, now standing together with me," Mr Chun said.

The Chinese interrogator stayed for a few more days before going back to China. But a few months later, he was back, this time staying with Mr Chun and studying international commerce at Korea University. It was at this time, that the interrogator, who has asked that he be identified only by his surname, Jia, met Mr Chun's daughter. "The summer came and my daughter who had been studying in Beijing came back home. Since my daughter spoke Chinese, the two clicked very well. My daughter took him to many places for sightseeing. They spent a lot of time together," Mr Chun said.

So it should not have come as a surprise when Mr Jia asked if he could be "friends" with the pastor's daughter. "I questioned him some more. And he said he wanted to marry my daughter." But to Mr Jia's surprise, Mr Chun refused the match. "Not because he was Chinese or because he was a prosecutor, but I told him that when I became a pastor, I pledged to God that I would find a pastor to marry her."

It is here that Mr Chun's recollection diverges with that of his former jailer. Mr Chun recalls that Mr Jia told him he was prepared to become a pastor, and with that the marriage was granted. But Mr Jia, in an interview in Beijing, said he only told his father-in-law he was thinking about joining the church. In fact he did not become a pastor and went on to work for a multinational company in Beijing, where he lives with Mr Chun's daughter.

The wedding drew an unusually large number of guests, many of whom came to see the marriage of the interrogator and the prisoner's daughter, Mr Chun says with a laugh. But while his efforts to free North Koreans eventually brought happiness to his daughter, he is no longer able to see her as he has been banned from travelling to China until 2012. "What my father-in-law does goes against the Chinese law. I am his son-in-law and live in China. I also sometimes feel that I am watched," Mr Jia said.

Mr Chun, meanwhile, has become an expert on North Korea. "In the past, North Korea was an isolated country. People there really believed that they lived in a paradise. But as the number of refugees increases, and as more information penetrates society, North Koreans also know the truth and what the outside world is like. But they cannot do anything about it due to the government's repressive policy," Mr Chun said.

"But it won't last long." slee@thenational.ae