Afghan politicians, religious leaders and elders gathered in the capital Kabul on Monday for a traditional meeting focused on US-led peace negotiations. More than 3,000 people have been invited to the rare loya jirga, which is billed as the largest in modern Afghan history and is meant to provide a platform for eventual intra-Afghan peace talks with the Taliban.

The need for intra-Afghan dialogue has never been more apparent but achieving it is proving difficult. The Taliban says the government in Kabul is a puppet regime and will only meet US officials. The insurgent group opposes the loya jirga, raising security fears that it could be attacked, and extra security forces have been deployed across the city.

On Saturday, US special envoy to Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad visited Kabul to meet Afghan president Ashraf Ghani. Afterwards, the two stressed the need for an intra-Afghan dialogue, before Mr Khalilzad travelled onwards to Qatar to meet the Taliban.

Their conclusion that peace would only come when Afghans sit down to speak with other Afghans is something that communities across the war-torn country have been arguing for years.

But peace efforts between Afghanistan’s government and the Taliban fell apart last Friday when the intra-Afghan dialogue, scheduled to take place in Doha, was postponed indefinitely because of a disagreement over a long list of proposed government participants.

While the US and Taliban made some progress during talks in February, neither a ceasefire nor the withdrawal of foreign troops from Afghanistan has been agreed upon. Meanwhile the Taliban have announced their annual spring offensive, resulting in a fighting surge throughout the country.

Communities in the southern provinces Kandahar and Helmand say that to achieve lasting peace, efforts have to start locally and need to focus on an overarching rural-urban divide, and corruption, both of which have fuelled violence across the country.

“Permanent peace starts at my doorstep and must begin by addressing social issues such as poverty, lack of services and tribalism,” said Mohammed Ishaqzai, the district governor of Panjwai. “That’s why an Afghan-led peace process is necessary. Even if it starts in Doha, it certainly can’t stay there.”

Panjwai district in Kandahar province – previously Taliban heartland – has been one of the war’s deadliest flashpoints. During the height of the conflict between foreign and Afghan forces against the Taliban, airstrikes and raids were an almost nightly occurrence.

Today it is mostly peaceful, something Mr Ishaqzai attributes to the community, rather than any military victory over the Taliban.

“It’s the people who stepped up,” he said. “They wanted peace. Many joined the police to ensure safety for their villages. The Taliban has been driven out of the district and our elders now solve conflicts – such as water or land disputes – between communities.”

The scars of the war are ubiquitous in Panjwai. Bullet-riddled and destroyed homes stretch to a desolate horizon interrupted only by treeless hills. Most people here are farmers, struggling to irrigate withered fields. Limited government services fuel people’s anger.

“After years of war, our district wants peace,” said Mr Ishaqzai. “People have disagreements, but what unites them is the frustration that rural people are left behind. What happens in Kabul and Doha is far away. It needs to happen here.”

This divide is part of the reason people took up arms in the first place, according to Mohammed Ahmed, a middleman in the opium business, who liaises between farmers and the Taliban in Helmand province.

He sits on an embroidered crimson rug in his new home, faded blue curtains blocking the views through the windows. His old house, a mud-brick ruin a few metres away, was hit by a US airstrike six years ago. Mr Ahmed’s mother was killed and several of his children injured in the bombing.

Kabul’s decision-making elite ignoring rural poverty has driven many to join the opposition, he said. “Peace talks in Doha alone won’t stop the war here. It’s the corrupted leaders in the government that need to leave – they are who the Taliban are fighting.”

Mr Ahmed complains that government authorities have blocked his attempts to start a legitimate business, and says that drug trafficking is the only way for him to support his family.

The fighting will only end when local grievances are addressed, he believes. “Peace can’t come from the top down – but rather the other way around. As for the corrupt leaders, I want them killed,” he said, rocking his youngest toddler daughter in his lap.

After 17 years of war, the Taliban controls or exerts influence over roughly half the country, and casualties continue to rise. For this reason, many Afghans hope for an immediate ceasefire. But for this to happen, Mr Ahmed believes that the Taliban needs a role in the government.

Across the country, civilians continue to be caught in crossfire in the interminable fighting. Last year, 3,804 civilians died, including 927 children the United Nations say. More than 7,000 people were wounded – the highest number recorded since records were kept.

Sixteen-year-old Razia is younger than the war itself. She lives on the frontline in Helmand’s Marjah. Her house was rocketed earlier this year by the government. The blast killed two of her sisters and a brother. She suffered burns and a broken leg, and remains in the local hospital. Speaking from her bed in the ward, the green-eyed girl with thick brown hair peeking out under her headscarf said she has never been to school, explaining that her parents always thought it too dangerous for her to go.

"I'm afraid myself and I always have been. I don't know what will happen when I go home again," she said.

But education and government services are exactly what will help bridge the country’s urban divide, leading to less violence, Nawa-i-Baraksay District Governor Ayub Omar Omari believes.

"A US-Taliban deal will affect rural Helmand little at first. It's not enough that two of the three parties of the conflict are engaging in discussion. Besides that, our social problems still remain," he told The National.

A turbaned man with a black beard and a white shalwar kameez – traditional baggy pants and long tunic – he sits cross-legged on his the couch in his new office. The old one lies in rubble a few metres away, destroyed by the Taliban. The militants control part of his district and the frontline is a short drive away.

“Eighteen years ago, the Americans came to remove the terrorists, but they didn’t succeeded. Instead, they are sitting at a table with them,” he said. “It’s not easy. The narcotics industry and warlords fuel the war. A straight divide between the government and Taliban in rural areas is not clear-cut. You’ll find many families that, under one roof, have both Taliban and government supporters.

Khadija, 19, lives in such a household. She has already been married three times. First to a Taliban fighter, then to a police officer and now to a man who used to help translate for the US military. Two of her husbands died; all of them were brothers and the young woman says it has never been a problem to have supporters of all sides of the war live in the same house.

“The real problem has been access to resources. We don’t have much here in rural Helmand, while the rich people in Kabul lives in plenty. For a ceasefire to last, this gap needs to be closed,” she said quietly, speaking from her home in a suburb of Lashkargah.

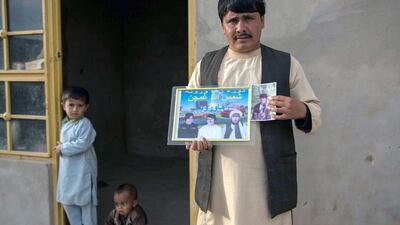

In a small box, she keeps photos of her deceased husbands. As a young widow – she married at 15 – she had no choice but to stay with her in-laws and marry the next in line. “My husbands were fighting on different sides, but they all wanted the same thing: peace, justice and an improvement to our rural lives.”

With future negotiations in limbo, the High Peace Council, the official government body tasked with liaising with the opposition, says that it is now up to the Taliban to announce their readiness for direct talks with the state.

"Afghan citizen call for an end to the war," the council's spokesperson Sayed Ihsan Taheri told The National. "Peace is a must for all Afghans – including rural communities."