BAZARAK, Afghanistan // The opening salvo in the September 11, 2001, attacks occurred not on a Tuesday in the United States but two days earlier in a windblown, dusty town in Afghanistan near the border with Tajikistan.

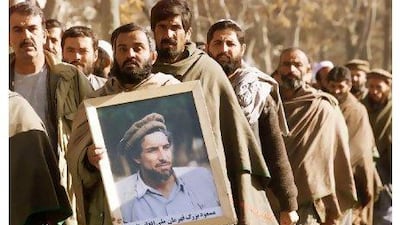

It was there that two Tunisians posing as reporters set off a bomb hidden inside a video camera, killing Ahmad Shah Massoud, the charismatic "Lion of Panjsher" and leader of the rebel Northern Alliance, a stridently anti-Taliban and anti-Al Qaeda rebel group.

Osama bin Laden is widely believed to have orchestrated Massoud's assassination as a favour to the Taliban, whose protection would be critical after the 9/11 hijackers, already moving into place in Boston, Newark and suburban Washington, carried out their attacks.

Like the 9/11 strikes, which US authorities later concluded cost between US$175,000 and $225,000, Massoud's killing was cost-effective and bore all the hallmarks of careful planning. The video camera had been stolen nine months earlier from a photojournalist in Grenoble, France.

A decade later, Massoud's followers insist that the celebrated foe of the Taliban and Al Qaeda would bristle at his link with the victims of the 9/11 attack.

"If Massoud was alive, he would be fighting the Americans," said Shahazada, a Northern Alliance commander who served under Massoud and goes by only one name.

"He was very intelligent, and he wanted to seek support from all countries. When I last met him before he was assassinated, he didn't want America as an ally. He didn't trust them," said Shahazada, standing near the soaring stone monument high in the Panshjer Valley that houses Massoud's tomb.

Far below on the valley floor, next to the rushing emerald waters of a river, are the rusting carcasses of Soviet tanks - a reminder that in the past three decades, war and alliances of convenience have been the rule, not the exception, in Afghanistan.

While being revered as a hero by many Afghans, Massoud is despised by others as one of the warlords who helped destroy Kabul with indiscriminate shelling during the civil war in the 1990s. Later, he and the Northern Alliance received millions of dollars in covert aid from the US Central Intelligence Agency to fight the Taliban and gather intelligence on Al Qaeda.

But even one-time followers of Massoud are disillusioned by the 130,000-strong US and Nato "stabilisation" presence in Afghanistan. That disaffection, even resentment, shows how deeply Afghans, not only in Taliban-influenced areas, feel the international mission here has failed them.

"Massoud wanted an independent Afghanistan, not a foreign invasion," said Shokrullah, a former Massoud fighter and intelligence agent in Panjsher. "He wanted support to fight the Taliban, but he opposed all foreign interference in Afghanistan - whether it was the US, the British, Pakistan or Iran."

Massoud's associates and residents of Panjsher have undoubtedly fared better than most in post-9/11 Afghanistan, securing top government positions and fortifying the Panjsher valley from the violence that plagues the rest of the country.

Still, violence elsewhere in Afghanistan is at its highest level since the US-led invasion a decade ago, and corruption and desertion plague the Afghan security forces.

Responsibility for security in the Panjsher and six other key areas was turned over to Afghan security forces by Nato in July, when foreign troops began their gradual withdrawal that will see all combat forces out of Afghanistan by 2014.

"As I knew Massoud, he was a man of freedom, and his goal was peace," said Noorullah, who ran a rebel logistics cell out of Massoud's home in the Panjsher Valley.

"Maybe he would agree with the Karzai government, but he would not like the path the US is taking in Afghanistan right now. There's more violence, there's more war. He wouldn't accept this.

"When I fought in the resistance against the Taliban, I was optimistic. We had morale, and we felt we had something worth fighting for. Now, we have no hope."