In Ras Al Khaimah, there was once a neighbourhood known as ‘the Baluchi Village’ at the base of the mountains. In this village of plywood huts and old concrete houses strung with UAE flags that multiplied with each passing National Day celebration, lived the bidoon.

The word means ‘without’ for they were the stateless and without passports. Their families, by chance and circumstance, were not granted citizenship when the UAE formalised its borders on its formation in 1971.

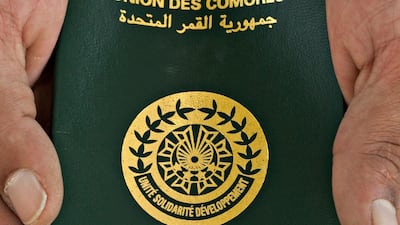

The families who live here hold Comoros passports and speak Arabic.

Today marks ten years since the Government began one of its largest directives to solve the bidoon question.

On September 6, 2008, the Ministry of Interior announced the formation of a committee that would assess the status of all bidoon in the UAE, with a view to naturalising those who are eligible.

Two days later, thousands travelled to registration centres across the country for the first day of registration, anxious and hopeful.

More than 7,000 application forms, one for each family, were given out by the end of the first day. In the following months, one by one, people presented their cases to officials in face to face interviews. Official statistics place the number of bidoon at about 10,000, though other estimates have been much higher.

That year, the UAE made a deal with the Comoros Islands, an Indian Ocean archipelago and one of the world's poorest countries, that it would grant passports to the stateless in the UAE, although it would not extend citizenship or the right to residency in Comoros.

A decade on, much has changed. The bidoon now hold passports of a country that many had never heard of 10 years ago. Minority communities in the Northern Emirates have integrated more closely with Emirati families.

“There are some things that are better,” said Waheed Shaheri, 30, a Comoros passport holder and government employee.

“Things changed a lot. Before we could not go out of the country and a passport made a lot of things easier. But some things are hard."

The situation the bidoon find themselves in is seen across the Middle East and farther afield.

UNHCR figures from 2014 estimate there were about 120,000 stateless people in Iraq, many are Faili Kurds, at the time. In Kuwait, the report estimated there were about 90,000 to 140,000 bidoon, most of whom were not given citizenship when the country became independent in 1961. But the UAE and Kuwait are the first to come up with a scheme to grant them passports.

_________________

Read More on citizenship:

Emirati mothers rejoice at formalising their children as citizens

Ninety-seven children of Emirati mothers, expatriate fathers get UAE citizenship

Citizenship hope for UAE's stateless

_________________

The RAK Baluchi village Mr Al Shaheri still calls home has almost emptied. Residents have moved downtown to a 17-storey highrise in the city’s Al Nakheel district, known as Burj Al Baluch, the tower of the Baluchis. At night, neighbours meet beside the parking lot to play the Baluchi game of Hashti, throwing wooden sticks onto a patch of stamped earth.

The building is lit by glowing multi-storey portraits of Ras al Khaimah’s Ruler and Crown Prince that shine on the lot below. Rent and utilities are provided free of charge by the RAK Government, say residents.

Comoros passport holders who approach the Ras Al Khaimah Royal Court have their cases fast tracked to to charity organisations who help with medical and financial assistance.

“We went to the Emiri court for help and the sheikhs didn’t cut corners,” said one of Hashti players, a resident who helped organised the neighbourhood move to the skyscraper.

“The sheikhs arranged everything, for here we are living and here we were born.” The RAK Royal Court and Ministry of Interior did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

In Abu Dhabi, many bidoon are the descendants of families that migrated between what is now Saudi Arabia, Oman and the UAE. In the Northern Emirates, the bidoon predominantly originate from the Makran coast, a semi-arid strip in modern Iran and Pakistan. In a time before borders, travel across the Gulf was common.

Until the mid-2000s, the stateless were granted state benefits like education and healthcare. They could drive, work, marry Emiratis and buy property.

Their status changed in 2004 when the Emirates Identity Authority was formed and the national ID card project began.

Prior to 2004, those seeking citizenship had to go through their emirate of residence and then the Ministry of Interior in Abu Dhabi. From this point, applicants had to go directly to the Ministry of Interior with a locally-issued family book, a document that traces genealogical descent and is only owned by Emirati men and unmarried women over the age of 34.

This federalised the citizenship process and created a new class of bidoon: those who had held passports but did not have family books lost their claim to citizenship. The family book also became a prerequisite for citizens to acquire an ID card.

Without UAE ID, bidoon were no longer eligible for state healthcare and education. Birth certificates, driving licences, vehicle registration and marriage certificates were only possible for documented citizens and residents with visas.

Mr Shaheri’s brother Ahmed came of age during this limbo.

“I couldn’t get work without a passport,” said Ahmed, 26, who was able to obtain a government job after obtaining a Comoros passport.

“I couldn’t get a licence without a passport. Those who had work could continue but those without it could not get work. I graduated and I had no work.”

At this point they were advised to apply for Comoros citizenship as a stepping stone to Emirati citizenship. Most in the Baluchi village received Comoros passports by 2012.

“I have this passport but I still don’t understand what this passport is for,” said Mohammed Mahmoud, 27, a government employee whose grandparents were born in the emirates.

“We’re from the UAE and everything we have is here and we were born here but they cannot give an Emirates passport. So they give us a Comoros passport.”

Comoros passports removed bureaucratic barriers to integration, by enabling bidoon to school children alongside Emiratis and inter-marry once again.

Mr Shaheri married an Emirati, which would not have been possible a few years earlier. They have continued to live with his family in the Baluchi village in Ras Al Khaimah.

Education opportunities have improved. Children are once again allowed to enrol their children in classes with Emiratis for an annual tuition of Dh6,000, said a Ministry of Education spokesman.

Parents like Mr Shaheri consider this a better quality education and essential to maintaining integration.

Parents of his generation teach children Emirati Arabic as a first language.

_________________

Read More:

Kuwait says stateless to be offered Comoros citizenship

Arabic News Digest: Kuwait and other states must find ways to help the bidoon

Saloon: Emirati identity in the novel

_________________

Mr Shaheri grew up speaking Baluchi. When he began school, he did not speak Arabic and spent months catching up with Emirati peers. He and his wife are raising their children with Arabic and Baluchi.

Mr Shaheri’s neighbour, Mustafa Juma’a, speaks Arabic, Baluchi and English to his one- and two-year old daughters. Mr Juma’a feels Arabic is for identity and English is for opportunity.

“English means work anywhere,” he said. “Arabic because we are an Arabic country. We cannot find any benefit for this Baluchi language.”

Their generation appreciate the value of formal education in a way their parents did not. In the past, it was easy to secure jobs without a diploma.

Mr Juma’a, was not pressured to complete secondary school. The former public relations officer, fluent in four languages, has been out of work since 2016 and struggles without a diploma. “That company I worked with before, they needed only language,” said Mr Juma’a, who is 32. “Now, people want certificates.”

Not everything has improved with the introduction of passports.

Many rely on local charities for assistance with utility bills, wedding costs and healthcare. These charities co-ordinate with the Emiri courts.

“We have a long list of names,” said Doa’a Alshaabi, a social worker with the Saqr Bin Mohammed Al Qasimi Charity Foundation. “First of all, they need education to help their lives. A lot of them marry young and both the wife and the husband are not working.”

Abdul Haikle, a Comoros passport holder who retired from the military in 2007 after decades of service, has pain in his knees but says the operation he requires costs Dh40,000.

Mr Haikle came crossed the Gulf from Makran in the 1960s at age 13. Now 61, he cannot afford knee surgery.

“Before we had a [health]card and even if we didn’t, we had money,” said his friend, who asked not to be named.

“The difference is before we didn’t pay for residency, for hospitals or schools.”

The majority of charity cases at the Saif bin Ghobash government hospital in Ras Al Khaimah are patients with Comoros passports, said hospital social workers. They receive three or four cases a week.

Buying property presents another obstacle. Comoros passport holders are not entitled to buy land available to Emiratis, once an easy process.

Most are on comparatively low salaries, often earning less than Dh10,000 a month. This makes it difficult to secure loans. In some cases, Emirati friends have bought houses for Comoros passport holders in their names.

The last large-scale registration drive was in July 2012, when the Ministry of Presidential Affairs assigned the Emirati Mothers Committee to oversee a programme to determine eligibility for citizenship. There have been several such initiatives over the years.

The process is ongoing.

“We want so many things for the future that we cannot do,” said Mr Juma’a.

“Nothing’s impossible. Just we will see. Allah kareem, God is generous.”