On a cool, grey April morning on Chicago's South Side, Rami Nashashibi walked purposefully into the conference room of the Inner-City Muslim Action Network (Iman) and sat at the head of a rectangular table, where four of his charges awaited instruction.

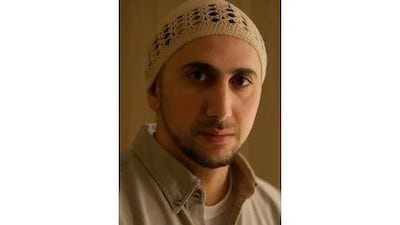

"I can't explain how much you have on your shoulders," Nashashibi, wearing loose-fitting jeans, a knitted skullcap and a comfortable sweater, told his men. "What we have right now is a little seed, and if we want that seed to become a great forest, we've got to cultivate it."

Nashashibi has been cultivating Iman for nearly 15 years. Today the organisation provides just about everything to those in need in Chicago Lawn, a predominantly African-American neighbourhood with a mix of Latinos and Palestinians. Its free clinic serves the sick from across the city. A computer lab offers technical training. Tens of thousands of people go to its annual concert benefit, Takin' It to the Streets, while its bimonthly music and arts gatherings are well attended. One project supports healthier eating alternatives for the area; another reduces gang violence. A new initiative, Green Reentry, builds eco-friendly houses for Muslims recently released from prison.

In 2007, Islamica magazine placed Nashashibi among the 10 Young Muslim Visionaries Shaping Islam in America. The next year he was named one of the world's 500 most influential Muslims by Georgetown University and described as "the most impressive young Muslim of my generation" by Eboo Patel, chairman of President Barack Obama's interfaith task force. Last autumn, the US State Department sent Nashashibi on a diplomatic speaking tour of Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia.

Earlier this year, Iman received another honour: Imam Habib Umar, the director of Dar Al Mustafa, a renowned institution of Islamic education in Yemen's Hadhramaut Valley spent an afternoon in Chicago Lawn as part of his first North American tour. He visited the organisation's Transitional House, where Muslim men recently released from prison stay until they can get on their feet, and delivered a speech on spirituality and community accountability. "The most beloved of God's creatures are those who are most beneficial to others," Umar had said, thanking Iman members for "fulfilling a communal obligation upon all Muslims".

Nashashibi balances a commitment to Islam, an intellectual rigour and an unstinting morality with the style and mannerisms of the street. He has a PhD in sociology from the University of Chicago, where he teaches, and has worked in high-security prisons and some of the city's roughest neighbourhoods. On the South Side, he is friendly with shopkeepers, businesspeople and political and religious leaders and trusted enough by school administrators to be called in to mediate student disputes.

"We must serve humanity by serving the creator in the most humble way possible," Nashashibi advises the men in the conference room. "What we do on all levels continues to represent the larger project. You're being watched now by Habib Umar. People around the city, around the country, around the world, are hearing about our work."

***

Nashashibi was born in Amman, Jordan, where his father, Ali Maher Nashashibi, produced a show for a local radio station. His mother - born as her family fled Palestine in the Nakba of May 1948 - grew up in Chicago, the eldest daughter of one of the first Palestinian families on the South Side. She met Ali Maher at university. The couple soon married and moved to Jordan.

Shortly after Nashashibi's birth, Ali Maher became a Jordanian diplomat and moved the family to Romania. The couple had a second son but divorced when Nashashibi was nine years old. He lived in Spain, Saudi Arabia and Italy with his mother and stepfather during his teenage years, until moving, at 19, to Chicago.

Yet he remains connected to Jerusalem, where his family name has been highly regarded since at least 1469, when Sultan Qatbay of the Memluk sultanate appointed Naser el-Deen Mohammed al-Nashashibi to guard Palestine's two holiest mosques, Al Aqsa in Jerusalem and Al Haram Al Ibrahimi in Hebron. A general in the Memluk army, Naser al-Deen is said to have built an arcade in the Al Aqsa courtyard that still stands today. About a century ago, Uthman and Raghib al-Nashashibi, second cousins of Rami Nashashibi's grandfather, represented Jerusalem in the Ottoman parliament.

After graduating from Chicago's DePaul University in 1995, Nashashibi went to Birzeit, just outside Ramallah, to work with local youth for a year. He says his visit was illuminating, but he decided to return to the work he'd begun on Chicago's South Side.

Two years prior, Nashashibi had met Abdul-Malik Ryan, a DePaul classmate. Originally an Irish Catholic from suburban Oak Park, Ryan was studying African-American history and had recently converted to Islam. "From the very beginning Rami was very charismatic," says Ryan, now DePaul's Muslim chaplain. Nashashibi asked him to help out at the Arab-American community centre in Chicago Lawn.

They started providing odd jobs for teenagers and daycare for younger children. "From there it was a step to have our own organisation, identified as Muslim," says Ryan, who co-founded Iman with Nashashibi.

Iman's reputation grew quickly. Its inaugural Takin' It to the Streets concert, held in Marquette Park in 1997, raised $15,000. "We thought we were millionaires and started nine programmes, with only one staff member," Nashashibi recalls.

"When we first started we were all young, we didn't know that much," adds Ryan. "We were kind of basing it all on enthusiasm."

They began to make an impact on the neighbourhood, though even today Chicago Lawn is no urban oasis. In early May, a 17-year-old Iman intern was shot in the back just a few streets away from the organisation's office. "We're not working in Disneyland," says Nashashibi. "This place, it'll test your mettle."

***

Metropolitan Chicago, with a population of nearly 10 million, has long been one of the US's most racially sensitive cities. In the so-called Great Migration, from the early to mid-20th century, millions of black Americans moved from the South into northern cities.

By the Sixties, organised white opposition groups viewed these new arrivals as competition for jobs and barred them from some communities, heightening racial tensions across the city. The neighbourhoods around Marquette Park - at that time, a patchwork of Polish, Irish and Italians alongside newly arrived blacks and some Palestinians - were a tinderbox. In 1966, Martin Luther King led a peaceful march through the area as part of an effort to integrate the city's neighbourhoods. Counter-protesters threw bottles, rocks and bricks, one of which hit King on the head.

A few decades earlier, a young Chicagoan born of Russian Jewish immigrants had begun working to improve living conditions in the city's slums and ghettos. Starting in the 1930s, Saul Alinsky organised community movements in Back-of-the-Yards, a rough and tumble district that served as the setting for Upton Sinclair's The Jungle.

Over the years Alinsky developed a set of rules, which ultimately became the principles of modern community organising. Today they read like an instruction manual from Otpor, the Serbian-run pro-revolutionary movement that has informed many of the Arab Spring protesters: hide your numbers to look larger; focus on what you know; remind your opponent of their own rules and claims; use ridicule, which is infuriating and hard to counterattack; remember that a good tactic should be enjoyable; identify a responsible individual and attack him; maintain the pressure.

"In this book we are concerned with how to create mass organisations to seize power and give it to the people," Alinsky wrote in his 1971 manifesto, Rules for Radicals.

Barack Obama never met Alinsky, who died in 1972, but as a community organiser in Chicago's Altgeld Gardens he worked under an Alinsky protégé. On his first day organising, in 1986, Obama's boss handed him a long list of Gardens' residents to interview.

"Find out their self-interest, he said," Obama writes in Dreams from My Father. "Once I found an issue enough people cared about, I could take them into action. With enough actions, I could start to build power."

A quarter of a century later, in a cramped second-floor office a few blocks from Marquette Park, Nashashibi met with the leaders of local Christian and Jewish organisations looking to generate the power of cooperative action to deal with a wave of foreclosures and blighted abandoned homes.

According to one estimate, Chicago house prices dropped almost 30 per cent between 2006 and 2010, close to the national average. But over the same period, median home prices in Chicago Lawn plummeted by 70 per cent, from $220,000 to $63,000. The four zip codes surrounding Marquette Park have seen 8,700 foreclosures in the past three years.

Not far from Iman's offices, a one-block stretch of Washtenaw Avenue underscored how abandoned homes led to increased drug use, gang violence and neighbourhood instability. The organisation owns two previously abandoned homes here: one is its Transitional House, the other its first Green Reentry home. Work on the latter began in 2010. Ma'alem Abdullah, the tall, soft-spoken head of Iman's Green Reentry, expected his first tenant later this month and hoped to have six to eight men - all Muslims just released from prison, who must undergo a screening process - living in the house by the end of the year.

On a recent morning, two young men loitered on the pavement just up the road from the retrofit house. "See these guys down the street selling drugs?" asked Abdullah, shaking his head.

He pointed out two other abandoned homes nearby, one of which no longer had a front door. "This is an insult to the work we're trying to do, a slap in the face," Abdullah said, strolling in and finding a soiled living room carpet and scattered trash.

The trio of leaders at the foreclosure meeting hoped to devise a plan to reclaim abandoned homes and turn them into housing for troubled local families. Their first target was an abandoned two-storey house on Fairfield Avenue. In early April, the front door and windows were boarded up. Iman hopes to legally acquire the home and put a family on the second floor, an office on the first, and another family in the basement.

On July 28, a district court judge will decide whether to award Iman custody of the home. Meanwhile, Iman planned a demonstration event in front of the house with a diverse group of community leaders in late May. "We're testing the law," says Nashashibi. "It may be a bit of civil disobedience."

It's a familiar subject for him. In Theorising the Global Ghetto, the course he teaches at the University of Chicago, Nashashibi links urban underclasses in cities around the globe. During a recent class he told his students how, in the 1990s, rap music, hip-hop style and protests against authority became "the cultural export of the ghetto" and, ultimately, "vehicles for solidarity and emancipatory practices".

In his work, he discovered a straight line from urban oppression to protest to the religion of his ancestors. In inner-city communities he learnt more about the African-American narrative, which led to meetings with black nationalists and civil rights activists and finally to Islam.

"I wasn't brought up in any way a conscious Muslim. I don't think I even walked into a mosque until I was around 19," says Nashashibi. "Then I started meeting brothers who had become Muslim and who then started challenging me about where I was spiritually. The first time I opened the Quran was to debate these people, trying to disprove them ... That was my first real engagement with Islam and I think somewhere along the line I just came to a point where I had to accept a really profound spiritual shift. It was very much a conversion-type process, and like an early convert there were moments when I was hard to be around, I had that zealotry ... I was just blown away, discovering this new world."

Combining that zealotry with his years spent studying urban culture and working with ex-convicts has earned Nashashibi undeniable street cred. His interest in gang violence, urban social history and the language and motivations of hip-hop is no stylistic pose, but a major part of his life and work.

Take Rafi Peterson, who stole drugs and ran with gang members as a teen. He was convicted of first degree murder in 1985 and sent to prison. By the time of his release, in 1997, he had converted to Islam. A year later he met Nashashibi and the two began visiting Chicago area prisons to talk about religion. They noticed that many prisoners had difficulty reintegrating into society when they were released. The duo launched Project Restore in 2005, which helped write a bill that sought to divert non-violent drug offenders towards treatment and away from the downward spiral of reoffending. After much wrangling, it was passed by the Illinois legislature in April 2007. [Today Peterson sits on the Iman board and runs CeaseFire, a highly successful anti-gang violence programme.]

That same year, Project Restore started welcoming tenants to its Transitional House in a renovated Chicago Lawn home.

***

In March, after a year of national controversy over several mosque proposals and more than a dozen anti-Sharia bills across the country, US congressional hearings into radicalisation among American Muslim communities began. Led by New York Representative Peter King, a Republican, the hearings are seen by many progressives and Muslim leaders as something of a witch hunt.

"Muslims now are being held up to intense scrutiny, and it's unfortunate," says Nashashibi. "More than ever, we've got to be proactive. It's gonna get ugly, with the King hearings, the 10th anniversary of September 11, and the 2012 election coming up. We have to continue to demonstrate how we are working for good, working for change and creating facts on the ground that speak louder than any attack."

A December study from the World Organization for Resource Development and Education, a Washington-based think-tank, found that building a strong national network of moderate Muslim leaders could help counter radicalisation. Further, the report argues that strong Muslim leaders who work to discourage violence and promote pluralism offer a positive alternative for Muslim youth, one the government would be wise to promote.

This might explain the increased interest in Iman from the highest office in the land. In April, Nashashibi and an Iman team met with officials from the White House Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships to discuss a possible collaboration.

Nashashibi is always on the lookout for bridge-building opportunities, in part because Iman measures its effectiveness through the community connections it helps foster. When news of the killing of Osama bin Laden by US forces broke, for example, many US residents celebrated openly. Yet in a Twitter post the next day, Nashashibi cited an opinion piece written by a rabbi, who referred to Moses leading his people in celebrating the death of the pharaoh and his army. "The rabbi recalled God scolding the angels after they too began to dance and sing. "'We must not rejoice at their deaths!'"

***

"Rami is like a synergy," says Rabbi Capers Funnye, who runs a synagogue a short distance from Iman, and who has known Nashashibi for seven years. "He really is able to bring people together from diverse backgrounds, diverse needs, and show people how their needs relate to others and relate to the work of others."

This might sound like the recipe for a successful politician. Indeed, the parallels between Nashashibi and the US president are striking: Obama's father and grandfather were tribal chieftains, while Nashashibi comes from a long line of prominent Palestinians; their parents divorced at an early age; both lived in foreign countries, moved around in their youth and struggled with identity before working as community organisers on Chicago's South Side in their twenties and teaching civil rights-related courses at the University of Chicago in their thirties.

"There's a lot of familiar territory," says Nashashibi. Though he has supported a few city council candidates in the neighbourhood, he doesn't see himself running for office. "People have brought it up, but I don't think so."

Nashashibi prefers to do more of what he's doing now. Iman recently bought a 15,000-square-foot space across the road from its headquarters, and hopes to turn it into a clinic, arts centre, garden and classrooms. After organising events in New York and Washington, Iman also plans to establish a network of affiliates.

"Iman has kind of chartered a new model, a new course for Muslims working in urban America, addressing critical needs in the community," says Amir al-Islam, a history professor at Abu Dhabi's Zayed University and chairman of Iman's board of directors. "Young people are most vulnerable to the ideas of radicalisation, most prone to being recruited. We think we have something that young people can engage in and capture their imagination, get involved in civic engagement - and it's a way to manifest their faith that serves humanity."

International engagement may be next. Nashashibi has twice visited Abu Dhabi to meet with officials from the Tabah Foundation, which advises the government on Islam-inflected civil society projects, to discuss the possiblity of an Iman affiliate in the UAE. He has also met officials from Msheireb Properties (formerly named Dohaland), which is overseeing the construction of a new downtown for Doha, and the Doha International Centre for Inter-faith Dialogue.

Nashashibi argues in his University of Chicago course that the denizens of today's densely populated, low-income urban areas – whether in Doha, Chicago, Chongqing, Cairo, Mumbai, or Nairobi – are linked by common concerns and shared responses. And their numbers are growing. A recent report from McKinsey estimated that the world's urban population is increasing by more than one million people every week - and the majority of that expansion occurs in slums and ghettos.

Saskia Sassen, the Robert S. Lynd professor of sociology at Columbia University in New York, says the DNA of cities is not conflict, but commerce and civics. Two decades ago she popularised the term "global city," to refer to metropolitan areas creating and responding to the trends of globalisation. In an email she outlined the rise of "a global network of all kinds of weak actors, but very interdependent nowadays, that can actually raise hell, if you want, and contest what is happening".

Sassen, who has sat on conference panels with Nashashibi and is familiar with his work, thinks he is ideally placed to take a lead role in this network. "Powerlessness can become complex," she says in the email. "Rami's capturing of ... a strategic encounter in what is a devalued space for the larger society, the ghetto, ... is for me akin at some deep structural level to Tahrir Square and Benghazi."

David Lepeska is a freelance writer who contributes to The New York Times, Financial Times and Monocle, and previously served as The National's Qatar correspondent. He lives in Chicago.