The first thing the Western world gets wrong about the saluki, says Sir Terence Clark, is its name.

“When British travellers to the Middle East in the late 19th and early 20th centuries started to bring back these hounds, most of them didn’t know Arabic or speak it.

“So they wrote down what they thought they heard the Arabs saying, and the word saluki came in western usage and has stayed there ever since.”

To be correct, he says, it should be saluqi. And there are other significant cultural differences. The west, with its Kennel Club and prestigious shows like Crufts, has codified the dog almost down to the curl of its tail.

“We in the West are accustomed to judging a breed by a written standard whereas the Arabs have never had a written standard.

“Various writers in the medieval period have written down descriptions of the saluki, but not of a formal standard as we know it in the west.

"When you ask an Arab what is a saluki he will say immediately, it’s a hunting hound of the desert used for hunting gazelle, hare and to lesser extent if they get in the way foxes, jerboas and wolves.”

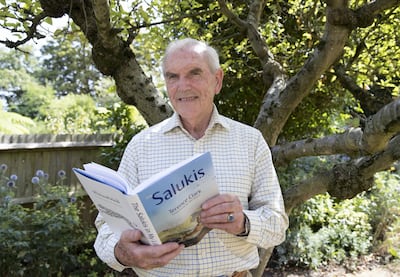

Sir Terence is an expert, both in the spelling and the culture of a breed that is said to be the oldest in the world.

He is fluent in Arabic and spent much of his life in the region as a diplomat, including Dubai in the 1960s, Jordan, Bahrain, and Oman and Baghdad as British ambassador, the former during the first Gulf War and the latter during the Iran-Iraq war in the late 1980s.

It was while serving in Iraq that he acquired his first saluki, on a slightly hair-raising trip to a Kurdish village perilously close to the front line, but which ended in a military escort back to Baghdad with his hard won prize, Tayra, a five-month old female.

He calculates he has owned around a dozen salukis since, with a litter of seven born in his London home, near the Thames at Putney, where he now lives with his wife Liese, after retiring in the 1990s.

Their stories, and his passion for the breed, are told in his new book, The Salukis in My Life.

His first encounter with a saluki was in 1973, in Oman with a dog that had been imported from Jordan. Even though he had spent nearly two decades in the region by then, including three years in what is now the UAE, salukis were kept either out in the desert, or hidden in private compounds.

“The saluki 30 or 40 years ago was very much a treasured object and you rarely saw one in the open unless you knew where to look,” he says.

“I did a lot of travelling in my early years in the Middle East but never saw one, but I knew about them from Arabic poetry.”

Of his own fascination, he says: “I suppose the romance was a strong factor. When you read about Arabic literature and tradition, the saluki and its role - it’s a bit like falconry and Arabian horses, the three traditional elements in Arab society. Horses were out for me, and so were falcons, but not hounds."

_______________

Read more:

Adihex 2017: Experience desert life in the city at hunt and horse expo

Dubai Saluki lovers develop park to let dogs run free

Salukis – blink and you’ll miss them

_______________

Now in his mid-80s, he decided after the death of his last saluki that he should not keep any more, on the grounds they might outlive him, but has somehow ended up with a former racing greyhound rescued from the nearby Battersea Dogs Home.

Research has shown that the saluki probably emerged as breed in ancient Mesopotamia, now modern Iraq, in the fertile crescent between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

Artworks showing dogs that closely resemble the modern breed have been discovered going back at least 6,000 years.

In 1987, the skeleton of a dog from 2,500 BCE was dug up in Tell Brak, once a city in north east Syria.

When compared by scientists with the bones of one of the first salukis brought back to England from Egypt over 3000 years later, the two were almost identical.

From Iraq and Syria, the breed spread north, south and east, through Turkey and Iran, into central Asia, and down to the Arabian Peninsula.

The first salukis may have been taken to Europe by soldiers returning from the Crusades, while a similar breed found in north Africa was likely introduced via Muslim Spain more than 1,000 years ago and possibly evolved into the greyhound.

“Individual populations have been influenced by the terrain over which they hunt, and the weather,” says Sir Terence.

“The further north you go, the hairier they become. Within that range you find a variety of hounds, all of them called saluki.

“So in northern Iran and Turkey it a rather bigger, heavier, hairier hound used for hunting in more mountainous terrain, perhaps deer rather than smaller gazelle and hare.”

His own research has included collecting saluki DNA for dog genome projects in Scandinavia and the US: “Literally from Morocco to China.”

Accepted as a world authority on the breed, he was invited in 2008 to judge the saluki beauty contest at the annual Abu Dhabi International Hunting Exhibition (Adihex).

He admits that beauty contests are, as he puts it in the book “really not my scene,” although says they do have a role: “A saluki has to look the part.”

Until it was banned in the UK, Sir Terence regularly took part in coursing with his dogs, hunting mostly hare and foxes. Hunting is also now banned in most of the Arab world, for conservation reasons which he understands, but points out it is not dogs which have cause such devastation to wildlife.

“Hunting got a bad name internationally because of the indiscriminate use of firearms. The odd bedouin with a saluki is not going to do much damage," he said.

Returning to the UK with his desert dogs, he noticed they were far more alert to their surroundings than those bred in the west for generations.

In the Arabian Gulf, though, he has noticed a growing passion for racing salukis, which keeps them fit and as nature intended.

“It has gripped the imagination of the youth of the Gulf and taken off on a vast scale. You have kennels with 300 animals. I like to make the comparison with the saluki in its heyday of the Abbasids in the ninth to 12th centuries when they had huge hunting establishments.”

From the start, Sir Terence has found that owning salukis “opened up doors to Arab society in a way that none of my colleagues enjoyed".

In Iraq he would drive though small villages and towns.

“And if people saw a saluki in the back of the car, they always said “come, in come in’ and before you knew it we were sitting on the floor with a meal and they were talking to me about life, their problems and hunting.

This passion for the bred might seem at odds with Islam, which teaches that dogs are unclean. In desert communities, though, it is often said that the saluki is not a dog.

Sir Terence says that the bred has learned to be discreet. “By tradition they are rather like children in Victorian times, they were to be seen but not heard. They have learned from long experience in the Muslim world, where dogs in general are unclean, to stay out of the way.

The teachings of the Prophet Mohammed are also supportive, he claims.

“It says in the Quran that you may eat of the meat caught by trained hounds. That gives a them a kind of status because the only hound the Arabs had in the time of Prophet Mohammed would have been the saluki.”

The Salukis In My Life by Terence Clark is published on August 27 by Medina Publishing