The camel beauty pageant season is upon us.

Every December, a small city of tents rises in the dunes of the Empty Quarter, 170 kilometres south-west of Abu Dhabi on the edge of the world’s largest continuous sand desert.

About 20,000 camels and their 15,000 owners compete at the Al Dhafra Festival, one of the world’s largest beauty pageants. It is distinguished by its "queens", long-lashed beauties with four legs and a hump. The prizes are not crowns but Range Rovers, Nissan Patrol pickups and, for the best, immortalisation in Bedouin poetry.

Reputations, and millions of dollars, are at stake.

The first days of trade, poetry and midnight dance parties are the prelude to the main event: the bairaq, the best herd of 50.

The bairaq is a competition for the wealthiest owners, who parade gargantuan beasts before judges to be compared head to head, nose to nose, eyelash to eyelash.

It is all in the name of namoos, a word of congratulations reserved for falconry competitions, camel races and camel pageants. Namoos best translates as the pride of victory and for competitors, it is priceless.

There are two bairaq competitions. One is for asayel camels, the sleek, short-haired hound-like racers. This title is won every year by a sheikh who holds court at a permanent camp on Al Dhafra’s highest dune, lit by a spotlight and a one-kilometre drive of green lights that guide through thick fog and dark nights.

__________________

Read more:

Everything you need to know about the Al Dhafra Festival

__________________

The other bairaq is for majahim, chocolate-brown camels that can grow to weigh two tonnes. Majahim, found in the western Arabian Peninsula, were only valued for milk until camel pageantry took off in the 1990s.

The modern pageant is credited to Rames Saleh Al Menhali who launched the first competition in 1993 after a long night’s debate with his father-in-law about whose camels were more beautiful. When dawn came and no agreement was reached, Al Menhali sent two friends across the Empty Quarter to find three independent judges, and convinced four others to join the competition.

The sport evolved into a multimillion-dollar industry thanks to government-sponsored festivals like Al Dhafra, launched in 1997. Substantial prizes guarantee the value of camels and prices have skyrocketed. A prized camel can sell for Dh12 million and it takes years to cultivate a distinguished herd.

Camels are marked out of 100 by five judges, with points allocated for each body part. Legs must be long, ears pert, eyelashes curled and the hump properly placed on the lower back. All decisions are unanimous.

Camel Botox and other sharp practice

In the past, owners spread fake news in the international media about million-dollar deals to trick rivals into withdrawing.

Pageantry scandals made international headlines in January 2018 when 12 animals were disqualified from the King Abdulaziz Camel Festival in Saudi Arabia for receiving Botox injections.

Others lie about the camel’s age to pit older, larger animals against younger ones. Despite the safeguards of microchipping, tooth checking and an owner’s oath on the Quran about the camel’s age, sometimes the temptation to bend the rules is too much.

Camel racing and pageantry are constantly evolving sports. Camels are prized because they are associated with heritage but their popularity is only possible due to technology.

'The competition is not between owners'

In a land preoccupied with prestige, the rumoured participation of a sheikh silences fireside chatter. “The competition is between the camels, not between the owners,” a competitor’s son told me when I asked his father who he considered his biggest challenger.

A few years earlier, this question would have been answered with a frank and detailed analysis of a rival’s strengths, flaws and strategic shortcomings. But the participants have become a tighter group of Emiratis, with fewer international opponents, leading to less open speculation.

After Saudi Arabia launched its own, bigger competition with $31.8 million (Dh116.7m) in pageantry prize money, the Saudis – once grand competitors – became less in number.

That competition has 30,000 camels in five categories: black, white, yellow, red and a reddish orange.

“Emirates is not like Saudi Arabia,” said Saudi Fahd Al Subaie, 31, whose camel, Tankha, won at Dhafra in 2018.

“More desert. More camels. More, more, more.”

Omanis were never into high-stakes pageantry. Qataris can no longer attend. The judging panel is now entirely Emirati.

With social media and a smaller community, words are carefully chosen. Nobody wants to show how much they want to win.

Even so, five days before the 2017 competition, speculation was rife.

Would it be Sari, the recording-breaking breeder and dealer?

Would it be Al Fendi, the 2016 reigning champion?

Would it be Sheikh Theyab, one-time winner and five-time runner-up?

Or would it be the local favourite Bin Mugrin, a breeder and trader from the nearby town of Madinat Zayed who had won every category except the bairaq itself? It was said he had been preparing for years.

Dhafra's Millions Street

At the centre of preparations is Millions Street, a road where millions of dollars exchange hands.

No independent authority determines the value of a camel. A camel’s value is its most recent bid, and bids increase as it is paraded down Millions Street, attracting the interest of prospective buyers.

A camel cannot compete in both group and individual categories within the same festival, so herds for bairaq are built over years. The week before bairaq is the final opportunity for herd perfection.

________________

Read more:

At the court of the camel kings in Abu Dhabi

________________

Friday is market day. Camels are followed by convoys of 4x4s and dancing fans who lead impromptu auctions with dance-offs, waving bamboo sticks as the beauty camels pace between them.

Breeders parade camels to attract buyers. Owners parade camels to intimidate competitors into withdrawing or overspending.

The street is lined with signboards for LED light and tent-rental companies, and makeshift shops selling hairspray to give the tufted ridge on a camel’s hump that extra volume, slippers for goats (protection from the cold, the heat and scorpions), and portable chimneys.

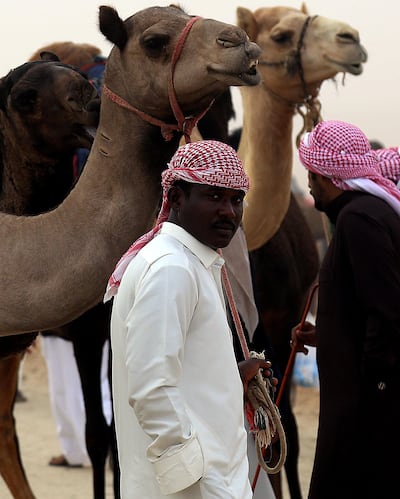

South Asian salesmen are ever present at the peripheries of dancing crowds, selling bamboo canes for dancing and sunflower seeds for grandstand snacking.

The superstars

A week before bairaq, campfire chat was about Sari, a record-breaking dealer who bought his first beauty camel in 1982 and set a record in 2008 with the first sale of a Dh10m camel.

Sari’s a known talent scout. He buys low for Dh200,000 or Dh300,000 and once his name has touched it, that camel sells for two or three million.

Born in the oasis town of Liwa, he joined a petroleum company at 14 as a driver and worked his way up.

“We love Sari because he represents the past,” one man told me. “All of those who worked at the beginning of petrol, they found money. Then he showed his hospitality. All people love him.”

Sari spent time at Dhafra relaxing with family around a chimney-topped fire in the midday sun.

“I learnt to focus and I improved,” Sari said. “I loved pageants and I focused on that. I didn’t buy the biggest camels but I bought the most beautiful.”

He dismissed the prospect of competing for best herd. The bairaq was terrible business. If a camel wins an individual competition, it can sell for millions. The bairaq only offered one million in prize money.

“Breeding is 95 times more profitable than bairaq,” said his son Ali Al Mazrouei. “One camel can win a Nissan Pickup or a Range Rover. If 50 camels compete as individuals, that’s far greater than the prize of the bairaq.”

Sari was out.

Then there was Khamees Al Fendi, a man said to have got his first beauty camel calf 'The Small' as a gift for helping a friend. The Small grew into a beast, a warrior in beauty and size.

But later that day, the news was out: Al Fendi had sold camels to Bin Mugrin. He was out.

With three days to go, the grandstand talk was about just two contenders: Sheikh Theyab and Bin Mugrin.

“I will tell you something, if you are not with the people, you will not know anything,” said Asha’er Al Amri, 29, an Al Ain breeder. “If you are not in the majlis, you will not know anything.”

Bin Mugrin’s success was assured by his relationships, said Al Amri.

"Every year he buys six or seven camels and this year he wants the bairaq," said Hamdan Al Mazrouei, 29, another Bin Mugrin fan. "To win, you must have good money. You must have a good look. You must have good people around you. And you have to have a good name."

Bin Mugrin had it all.

Foot-long tinsel tassels

Much can be discerned about a man’s strategy by his camp. Is he an entrepreneur or a traditionalist, a delegator or a one-man mastermind?

Bin Mugrin cultivated the image of a traditionalist, receiving guests in a goat-hair tent. Its ceiling was hung with foot-long tinsel tassels, its walls decorated with banners awarded for past pageantry victories.

An adjacent white tent with gilded chairs and images of ruling sheikhs was reserved for VIPs.

Bin Mugrin had come with family.

Colourful tents for the women were hidden at the base of a nearby dune, flagpoles just visible above the dune’s crest.

Bin Mugrin’s daughters did not attend the grandstands but were heavily involved. They joined convoys to the judging pens in 4x4s with tinted windows, and followed the day’s events on Millions Street and the judging pens through Snapchat.

________________

Read more:

A day in the life of a camel debutante

________________

For Al Dhafra, Bin Mugrin chose 60 of the best from a herd of 300, including three superstars: Sultana and Mintuba, both from Saudi, and five-year-old Heyafa. Admirers said Heyafa was the most beautiful camel in the world.

His herd was improving by the day. His grandson said he’d bought another two camels for four million that day. At least one was from Sari.

More surprises would follow, his daughter promised. “It’s a secret,” she said. “I know the secret but it’s a surprise.”

Sheikh Theyab

Optimism was growing at Sheikh Theyab’s camp.

It was down a long gatch drive marked by strings of purple lights that guided guests through the thick mist of humid desert nights, and matched the upholstery inside his 500-square meter tent.

Guests were greeted with chocolates wrapped in paper decorated with the faces of his two most famous camels, Jehada and Hakima. Their portraits also decorated tissue boxes and heavy glass incense holders presented as gifts to guests.

Bin Mugrin controlled his camp like a military commander. Sheikh Theyab delegated and everyone who helped felt invested in its success.

“You want a big camp,” says Tariq Al Sabaihi, Sheikh Theyab’s self-appointed bard. “The most important thing is hospitality. You want to spend money to bring others happiness, to gather friends, to know each other, to help.”

Immortalised in poetry

A man’s name is not made through hospitality alone. Renown is also spread through melodic poems known as shella.

Poetry is inspired by remarkable camels and can transform a contestant into a superstar known across the Gulf.

Camel poetry was once penned across car windscreens with photographs of the challenging animal. This has been banned but shella remains critical to a camel’s reputation, at fireside recitations and on social media, where clips of victorious camels and owners are set to tracks of recitations extolling their virtues.

Three days before the competition, Tariq was composing an 18-verse ode to Sheikh Theyab and his herd.

“Look,” said Tariq, holding a Nokia and an iPhone. “Look. This is Al Dhafra before, and this is Al Dhafra now. Sheikh Theyab placed first in bairaq two years ago and second last year. This year, God willing, he will get a perfect score.”

The Bairaq

On the eve of the competition, Sheikh Theyab was nowhere to be found.

He was hunting with his falcon in Pakistan.

“I’m really just doing this for my girls, because my older daughter is now 10 years old and she’s grown up with camels,” he said by phone.

“Al Dhafra means a lot to her.”

Sheikh Theyab had come second in 2013, 2014 and 2016, and first in 2015.

This year, he had participated in the 0-3 year old individual competitions and saved his best for the bairaq.

“There’s no secret to it,” he told me. “You just have to work hard and you have to buy camels.”

Superstar Jehada would compete in the bairaq with four sisters, all conceived by embryo transfer, and he would introduce one-year-old Mamlaka. “She’ll be one of the real superstars. Just today they saw her.”

He had distanced himself from all social media. “I’m trying to get out of all this but I’ll be back, hopefully after three days.”

'The only thing left'

The mood was subdued at Bin Mugrin’s camp, where poets appeared from the early evening for rounds of recitations. The banners on the back wall were removed for washing, to be rehung before the expectant triumph.

“He’s won all the individual competitions and all the other herd competitions,” said his son Saeed, 43. “The only thing left is the bairaq.”

“He makes the plan, and we his sons execute it.”

Bin Mugrin was fairly stoic.

“There’s no plan, no plan,” said Bin Mugrin. “We are Bedu, Bedu don’t have plans. Plans are for the military. This isn’t the military.”

And if he lost?

“That’s supposition,” he said.

Namoos

The morning of the bairaq arrived.

Four had entered. Two were surprises.

Eid Rashed Al Mansoori, 47, a breeder from the distant town of Ghayathi entered a herd he bred himself. Nobody expected Eid to win but whatever position he placed, it cemented his name as a herdsman.

Then, a wild card. Al Rashidi of Baniyas, real name Ali Mubarak, a 28-year-old newcomer known by few. Fewer still expected him to win. Al Rashidi said it was a last minute decision.

“Strategy brings surprise,” he said.

It was not namoos he sought, but victory of another sort. Al Rashidi knew people were shopping for a larger Saudi competition in two weeks and had millions to spend. Saudis would be in the stands, watching his camels all day long. It was better publicity than individual competitions, where everyone’s camels were mixed together.

In the bairaq, each owner has his own pen, so everyone could see Al Rashidi’s best 50 in one place. It was 12 hours of free advertising. Strategy, indeed.

That left Bin Mugrin and Sheikh Theyab.

Sheikh Theyab’s camel campaign manager was there after dawn prayers, watching hawk-eyed through the morning mist.

“They spent 20 minutes comparing just the first two camels,” he said. “Our camel’s head is better but her body is better. It’s tough.”

By noon, he had stomach problems and his legs were wobbly.

Bin Mugrin’s group never showed.

Judging began around 7am. After the first six hours, men returned to the camps for lunch and an afternoon nap.

The men returned, the judging went on, the hours passed.

The sun neared the horizon.

And then, a winner was decided.

Nobody saw it coming:

A ten-year-old girl – Sheikha Sheikha bint Theyab. Princess Sheikha, daughter of Theyab. Her father had registered in her name, a surprise to all but Sheikha and her sister.

They stood in matching golden dresses, composed and smiling as influencers and television crews circled. She was swept off to join the pen below, surrounded by men vying for the chance to Snapchat her with the herd.

The chaos paused for a phone call from Pakistan.

“Namoos baba,” she told her dad. Congratulations, daddy.

“Namoos.”