Just outside the National Stadium in the district of Surulere, in Lagos, Nigeria's biggest city, there stands a statue. Mounted on plain plinth is the bust of the footballer, Sam Okwaraji, his hair in shoulder-length braids, just as it was when he energised the midfield of the Super Eagles, Nigeria's national side, in the late 1980s.

During the last of his caps, on a hot August afternoon in 1989 at Surulere in a World Cup qualifier against Angola, Okwaraji collapsed in the 77th minute. His body convulsed on the ground and teammates immediately saw his condition was grave. Attempts were made there and then to bring him back to consciousness. He was pronounced dead in hospital.

Many Nigerians knew Okwaraji as a man with a big brain. He had ended up playing professionally in Europe - in Croatia, Austria and the German Bundesliga - having travelled there to study law.

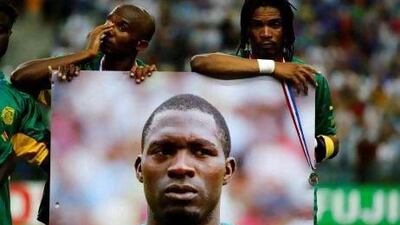

What they did not know and the autopsy on the 25 year old would strongly suggest, was that he also had an unusually big heart. That condition, a cardiomyopathy, probably contributed to his collapse on the field of play. A related condition is believed to have caused the death, in another international match, of the former Cameroon captain Marc-Vivien Foe, who collapsed during a Confederations Cup game in 2003 and died shortly afterwards.

Cardiac arrest has caused a number of fatalities among footballers and in recent years it has been noted that players with sub-Saharan African backgrounds seem to have been afflicted in unusually high proportions.

There is clearly insufficient medical information about the suspected heart attack suffered on Saturday by the 23 year old DR Congo-born Bolton Wanderers midfielder Fabrice Muamba, to relate his case to the others. But as the England Under 23 international, who moved to London from what was formerly Zaire aged 11, is still in a "critical condition" in hospital, what he will have is the sincere sympathy of many on the continent of his birth who have been directly affected by tragedy on the field.

Since the death of Okwaraji, four Nigerian professionals - Amir Angwe, John Ikoroma, Bobsam Elejieko and Endurance Idahor - a Liberian, Ambrose Wleh, a Chad international, Lokissimbaye Loko, a Zambian international Chaswe Nsofwa, and Cameroon's Foe have lost their lives because of heart problems while playing.

Several Africans, in turn, have had heart irregularities diagnosed during their careers, often alerted to them when they join European clubs.

The former Nigeria captain Kanu had already won an Olympic gold medal and the European Cup with Ajax of Amsterdam when, on signing for Inter Milan, doctors found a faulty aortic valve in his heart. An operation in America ensured he went on to a long and fulfilling career.

The Ivorian players Adama Niambele and Yussouf Kone both failed medicals with Italian Serie A clubs because they were found to have "enlarged hearts" that would potentially put them at risk.

The heart condition with which the Senegalese winger Khalilou Fadiga competed with distinction for several seasons at Auxerre in France and at the 2002 World Cup with his country was slightly different.

On joining Inter, their medical staff detected an irregular heartbeat and advised him to give up his career. Fadiga persisted with it, but after suffering a collapse while with Bolton, had a defibrillator fitted. Such cases are not uniquely African. The highest-profile deaths from heart problems on the field in the last five years both involved Spanish top-flight players, Antonio Puerta and Dani Jarque.

It has also been apparent, at least historically, that footballers in Africa had less regular access to sophisticated medical screening than typically a young footballer might receive in Europe, which would heighten the risk of unanticipated problems on the field, particularly in hot, difficult conditions.

But when a Fifa-backed medical research team focused specifically on heart risk among the players at the 2009 African Under 17 championship in Algeria, the team of academics involved found that "black African athletes seem to have an increased risk of adverse cardiac events during sports events".

They recommended improved screening procedures and awareness that, while sub-Saharan Africa may produce more than its share of talented athletes, a small but slightly higher than average proportion of them may be vulnerable.