Bob Arum watched Manny Pacquiao outbox a bigger and battle-hardened Oscar De La Hoya and, in an instant, knew he was witnessing something truly special.

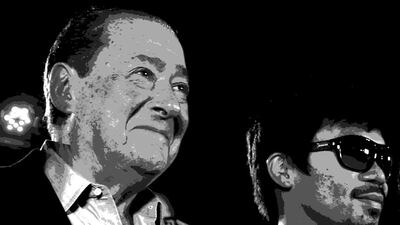

“He was so effective in demolishing De La Hoya that that’s when I realised we had a major-league talent on our hands,” says Arum, Pacquiao’s long-time promoter and confidant. “That was the fight that opened everybody’s eyes.”

De La Hoya presumably wished he could close his and forget all about it. The December 2008 defeat, secured once De La Hoya’s corner threw in the towel after eight heavily one-sided rounds, prompted his retirement and confirmed Pacquiao’s place at boxing’s summit.

The pocket-rocket Filipino then sparked out Ricky Hatton – it was later voted Ring Magazine's Knockout of the Year for 2009 and, Arum says, "the best I've ever seen" - and quickly followed that with a final-round victory against the formidable Miguel Cotto.

Already a six-division world champion and soon to ascend to an unparalleled eight, this was peak Pacquiao, “Pac-Man” in his prime. Or, for that matter, anyone else’s.

"That Manny Pacquiao was as good as I've ever seen a fighter on the world stage," Arum told The National over the phone from his Top Rank office in Las Vegas, not long out from his client's third skirmish with Timothy Bradley this weekend – a bout that Pacquiao has labelled his last.

Arum should recognise a boxing great when he sees one. Last week, he celebrated half a century in the fight game, 50 years of selling to the world the likes of Marvin Hagler, Roberto Duran, "Sugar" Ray Leonard, Evander Holyfield and George Foreman. It all began March 29, 1966 – with Muhammad Ali.

More reflections on Manny Pacquiao

• Manny Pacquiao, writes Jon Turner, was a showman, a true prizefighter and a legitimate boxing legend

It won’t end with Pacquiao on Sunday morning, even if Arum turned 84 in December, but it is safe to assume that in his remaining years the Top Rank chief executive will be hard pressed to unearth anyone who has transcended boxing as much.

Pacquiao is hugely popular in America and as close to a deity as they get in the Philippines, a genuine sporting superstar who plans to quit the ring in favour of ringed ballots in his homeland’s political system. Pacquiao was elected to the House of Representatives in May 2010; before and since, he has sought to bring social reform to his country of birth.

For that, Arum places him in illustrious company indeed.

“The fighter I had that had the most impact is clearly Muhammad Ali, but next to Ali, it’s probably Pacquiao,” he says. “He’s had a tremendous impact in Asia and in the Philippines where he’s a political figure, he’s resonated with the American public and the American media.

“So impactfully, next to Ali, I would put Manny Pacquiao as a man who has tremendous influence because of his career, because of his exploits in boxing and because of who he is on the dialogue around the world. Like Ali, Manny is greatly admired around the world.”

Arum’s admiration is understandable, but it had to be earned. Well-versed in the intricacies of the sweet science, he wasn’t greatly impressed the first time he saw Pacquiao fight live, an ill-tempered scrap with Agapito Sanchez in 2001, when HBO requested Arum place the up-and-comer on the undercard for Floyd Mayweather Jr versus Jesus Chavez in San Francisco. Given the large Filipino diaspora there, it made sense.

Back then, though, not everything did. Early meetings between Arum and Pacquiao were stretched out and stunted, whatever communication there was possible only through translators.

Listen: Jon Turner and Steve Luckings debate who ranks as the best fighter, pound-for-pound, of all time

“He couldn’t speak English and I certainly couldn’t speak Tagalog,” Arum says. “But gradually, because Manny’s a very intelligent guy, he learnt the language.”

In the intervening years, Arum has grown familiar with what he describes as Pacquiao’s many other qualities. The American, one of boxing’s most celebrated promoters, has been integral to his climb through the sport, carefully crafting Pacquiao’s tale from the breadline to the big time.

His past and profile has transported Pacquiao into the homes and hearts of boxing fans around the world and contributed to an estimated US$500 million-plus (Dh1.84 billion) in career earnings alone. Last year’s “Fight of the Century”, an admittedly disappointing denouement to his rivalry with Mayweather, generated more than $410m in pay-per-view sales – easily a record. Pacquiao reportedly took home $120m in purse.

It is almost as unlikely a story as Pacquiao’s rise from street vendor to superstar, but therein lies the allure. If Arum was the architect, Pacquiao’s persona made it all plausible.

“Manny really gets the credit for that, much more than I do,” Arum says. “Because Manny projected himself to the public as who he is and the public fell in love with him. He’s an extraordinary young man, he’s very sincere, he’s very God-loving, is extraordinarily charitable. My job was to present Manny as he really was and as he really is. And people just fell in love with him.

“Ultimately, particularly this long a period, the truth comes out and you have to live with the truth. And living with the truth as far as Manny is concerned is very easy, because he’s such a decent human being. He exemplifies everything we’re looking for in an athlete, everything we’re looking for in a human being.

“People are cynical. If you just portray that and there’s no substance to it, it quickly disintegrates. With Manny there was a substance to it. Portraying Manny as he is, as not how you want him to be, is what endeared him to the public.”

That is felt nowhere as keenly as in the Philippines. Much like his backstory, Pacquiao’s charitable endeavour is well documented, gilding his hero status, amplifying his appeal. For instance, in General Santos, a backwater place in the Mindanao Province where he resides, Pacquiao has contributed substantially to health care and education. Not only that, in fact.

Arum recalls one of the early trips he made there, where tuna is big business but an arduous vocation. Fishermen would spend up to three hours rowing antiquated vessels out into the deep water, briefly attempt to fill their nets with whatever catch they could, and then row three hours back to land. Actual fishing time was significantly limited; as such, revenues were too.

However, Arum returned two years later to find the entire fleet fixed with outboard motors, slashing the journey each way by around 75 per cent – to approximately 30 minutes. Thus, more time fishing, more tuna in the nets and more money in the pockets of those who needed it most.

Arum later discovered Pacquiao had donated the motors.

“That to me spoke volumes to who the guy was and conveyed how much he wanted to help his fellow people,” he says. “That’s his nature, that’s who he is. And when people like myself sometimes say ‘Manny, you’ve got to save your money, you’ve got many years ahead of you’, he just responds that he wants to spend his money dong charitable things; that God will always provide.”

This weekend, Pacquiao seeks to provide one more knockout, one more layer to his legacy inside the ropes. Or so the theory goes. He has lost to Bradley and then avenged that defeat, so the conclusion of the trilogy supposedly marks an appropriate conclusion to one of the finest boxing careers in history, a record that currently comes in at 57-6-2.

Pacquiao, 37, said as much on Monday, that his “mind says yes” to retiring his pugilist paws, although Arum remains not so sure. Long in the tooth and almost as long in the game, he understands that a fighter’s last bout can often be as vague as it is final.

“I’ve had experience with this retirement thing,” Arum says. “I’ve had fighters retire at a press conference and a half-hour later call me up and say they were unretired. So I take with a grain of salt that a fighter is hanging up the gloves, because so many of them say they’re going to do it and then change their minds.

“But if I had to guess I would say Manny, because he has this political career, may very well say this is it, win or lose, he’s hanging up the gloves. That’s up to Manny. Right now, if you ask him, he’ll tell you yes this is his last fight, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the end to me.”

Should Pacquiao retire, Arum believes Bradley-III represents the right juncture to call it a day. Not because the Filipino’s power is necessarily waning – according to Arum, Pacquiao has been delivering his weaker right hand in training with more power than in the past five years – but because of the opportunities life away from the ring can present.

Pacquiao the Pugilist can focus on Pacquiao the Politician, maybe even become Pacquiao the President.

Highs and lows

• Steve Luckings and Jon Turner team up to count down the best and worst of Manny Pacquiao: The Five

At present, he is running sixth in the polls to be elected senator in May, one of 12 new names to be installed on the 24-strong assembly for the next six-year term. Goodbye Sin City, hello Senate.

“This is the natural point in his life,” says Arum, who once served at the US Department of Justice’s tax division, under president John F Kennedy’s brother, Robert. “There’s the great AE Housman poem ‘To an Athlete Dying Young’, that athletes die young in a sense that their careers finish and that’s the pinnacle of their success.

“But as far as Manny is concerned, he has a bridge into public service and politics and that’s awaiting him. So in his case it’s not really an athlete dying young. Yes, his athletic career – his boxing career – is over, but a bright new career would be opening before him.”

But what about the road he leaves behind? If this is Pacquiao’s farewell to boxing, what of his legacy? Eight-division world champion, pound-for-pound the planet’s finest fighter, source of unquantifiable pride to his compatriots, beacon of hope in his country’s future. It is a heady mix, yet Arum is reluctant to pass judgment right now.

“Legacies are something for historians, and something that takes reflection,” he says. “Certainly it’ll be a very good legacy, certainly it’ll be wrapped up with him being a Filipino, certainly it’ll be wrapped up with what he’s meant to his people and certainly it’ll include his exploits in the ring.

“But how exactly that legacy is going to be treated is not for me, it’s for the historians. Like Muhammad Ali, who was extraordinary as a fighter, his legacy is really less about his fighting ability as to what he meant with the stances that he took, the positions that he held.

“That’s more his legacy than the great fighter that he was. Eventually, Manny could go some way to replicating that.”

jmcauley@thenational.ae

Follow us on Twitter @NatSportUAE

Like us on Facebook at facebook.com/TheNationalSport