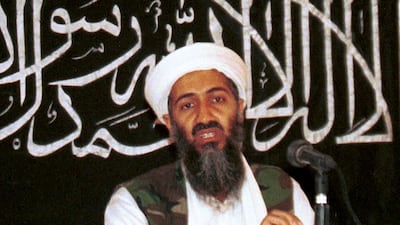

Spanning 255 pages, the diary of Osama bin Laden, recovered in the American raid in his compound in Pakistan, is a valuable journey through the mind of an influential figure in the world of jihadism. The handwritten pages document bin Laden's intense reactions to the events unfolding in the Arab world over the course of two months, beginning on March 5, 2011. The last page was written in the dawn and evening of May 1, apparently a few hours before the raid that led to his killing in Abbottabad at 1am the following day.

Over the two-month-long commentary, Bin Laden offers his views on the uprisings that swept the region in 2011 and how jihadis should react to them. In some instances, he credits his own speeches and organisation for laying the groundwork for the “revolutions” and the way the United States reacted to them. The pages offer an insightful delve into the mind of a jihadi leader the world only knew through his occasional statements, rare interviews to journalists and the testimonies of those who engaged with him. Particularly important is the fact his commentary involves the most significant developments that swept the region he cared about the most.

In the handwritten pages, which are extremely difficult to read, one observes a person who speaks his mind. A contemplative mindset shows up in frequent statements like “a thought struck my mind” as he listens to a statement again or thinks about a draft for his next letters or speech. Throughout the pages, he clearly shows various emotions and character traits, from excitement to a lack of sophistication, self-importance, opportunism and cynicism. He even relates dreams he had in the tranquillity he enjoyed in the compound during his remaining days. In one instance, he decides to issue a statement to Muslims based on a dream he saw and interpreted himself.

While most of the pages discuss events he followed through Arabic satellite channels, the notebook includes occasional direct references to Bin Laden's core belief and world view. In this context, his relationship to Islamism deserves particular attention — at least, given the academics' tendency to overlook these roots and how they play out within the legacy he left behind. In the earlier pages, Bin Laden says he grew up in an ordinary family, who did not think of Islam beyond religious practices that every Muslim is required to follow, such as prayers, fasting and good conduct. He said he first became "committed" — a word that could mean anything from a more consistent religiosity to varying degrees of strict and systematic lifestyles — through his affiliation to the Muslim Brotherhood.

He emphasises that the Brotherhood's religious influence on him "was not much". The latter statement is often a reason why academics, who study these issues mostly in the abstract rather than through close interaction and observation, downplay this aspect of influence on jihadis. But such a view misses the mark, since political Islam's contribution to jihadism has less to do with theological or religious influences. Instead, it is more about the political and revolutionary ideology that requires closer knowledge of the revolutionaries — in this case jihadis — and the context and the environment in which they operate. When Bin Laden discusses this issue, he mentions the word ilmi, which means theological or religious. Scholars in Arabic, for example, refer to traditional salafism as salafiyah ilmiyah, as opposed to activist salafism (salafiya harakiyah), which includes a revolutionary aspect. Hence, Bin Laden said he grew up within the Muslim Brotherhood but he did not attain much traditional religious training from the organisation.

He also named Necmettin Erbakan, the former prime minister of Turkey and the father of modern Turkish Islamism, as a source of inspiration as he embarked on his journey of radicalisation. In the latter pages, he mentions a number of influential clerics in the context of promoting Al Qaeda's ideology. Those clerics overwhelmingly come from the sahwa movement that took place in Saudi Arabia and other countries in the 1970s, which combined the revolutionary ideas of political Islam with traditional salafi concepts.

Following the trail of Bin Laden’s thoughts through the handwritten pages, one can sometimes forget that the person speaking is a jihadi leader. He could be mistaken for any Islamist. Throughout the pages, he cheers Islamist rise in the region. He suggests that the prominence of their role is vindication that Islamists are the default fallback position of societies in the Middle East. He even remembers that a speech he gave in 2004 argued that Muslims could choose or remove their leader, contrary to prevalent view within salafism, much as the Arab uprisings did.

His general commentary provides a journey through his thought process that could not be attained elsewhere, except by those who accompanied him. The diary also captures a tone that no study of jihadis’ book titles and speeches could convey, an ideology and a world view that are heavily influenced by political Islam. Of course, Bin Laden’s jihadism and political Islamists diverge on key issues, such as actual engagement in jihad as a way of life and the apostatisation of Muslim rulers. While both of these differences can still be accepted by some non-jihadi Islamists in certain contexts, with Al Qaeda, and more so with ISIL, these differences inform a more systematic and broader ideology that prohibits the peaceful engagement in an un-Islamic political order.

Despite these significant differences, key commonalities remain. Those include the early inspiration and the world view, as shaped by the early upbringing of Bin Laden and numerous leaders of modern jihad. Then there is the political ideology that justifies what traditional salafism does not justify, including suicide bombing and the systematic use of political violence. Justification of such acts is often provided through effortless reasoning involving military necessities and power dynamics, which traditionalists reject based on religious texts.

The Bin Laden notebook should help rethink established, and often stubborn, assumptions among academics and observers about jihadism. Our understanding of jihadism today tends to be shaped by work that was written a decade ago, when scholars knew so little on the mysterious phenomenon of jihadism. The years since the Arab uprisings and the subsequent rise of jihadism in our region, have brought piles upon piles of new data and insights. Some of them are available in bad handwriting, others in isolated and unnoticed events or in spoken testimonies. Scholars have to roll up their sleeves to understand why the jihadist world view seems to find new recruits, despite more than 16 years of war on terror.

Hassan Hassan is a senior fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy