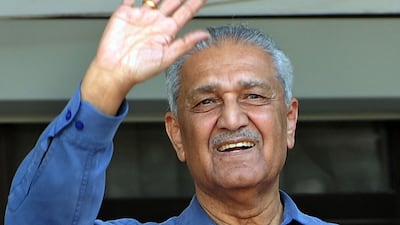

No one arguably did more in the conquest of nuclear technology in the Muslim world than the legendary Pakistani nuclear scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan, whose death at the age of 85 from complications relating to Covid-19 was announced at the weekend.

Known in his home country as the “father” of Pakistan’s nuclear bomb for the central role he played in the development of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons arsenal, Khan was accused by Western intelligence of using his expertise to run a major proliferation network, aiding programmes in Libya and Iran.

Khan’s international proliferation activities were also said to have links with North Korea, whose own successful efforts to acquire nuclear warheads has been the cause of significant tension between Pyongyang and the United States.

Khan’s involvement in these activities led then-CIA director George Tenet to label the Pakistani scientist as one of the most dangerous men in the world, commenting that he was “at least as dangerous as Osama bin Laden”.

And it was because of the intense pressure Islamabad came under in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks that Khan’s activities were eventually subjected to close scrutiny by the Pakistani security forces, with the result that Khan was placed under house arrest for several years.

But while Khan remained a highly controversial figure in Western intelligence circles, the central role he played in helping his homeland to acquire its own nuclear weapons capability made him a national hero, an attribute that was clearly evident in the tributes from leading Pakistani politicians after his death.

Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan described the scientist as a “national icon”, and praised his “critical contribution” to making Pakistan “a nuclear weapon state. This has provided security against an aggressive much larger nuclear neighbour.”

Khan became immensely wealthy as a result of his involvement in exporting Pakistani nuclear technology, leading to claims that his primary motivation was financial gain, not fulfilling his patriotic duties. But Khan himself strongly refuted these suggestions, arguing that he wanted to break the West’s monopoly on nuclear weapons.

As BBC journalist Gordon Corera, who published a 2006 biography of Khan, has written, the scientist was highly critical of what he saw as Western hypocrisy regarding nuclear weapons, questioning why some countries were allowed to keep the weapons for their security and not others. “I am not a madman or a nut,” Khan once said. “They dislike me and accuse me of all kinds of unsubstantiated and fabricated lies because I disturbed all their strategic plans.”

Nevertheless, it is evident that Khan’s proliferation activities made a significant contribution to creating a number of global security issues, in particular Iran’s controversial nuclear programme.

Iran's centrifuge programme at Natanz, for example, where the regime has been accused of seeking to produce weapons grade uranium, was built primarily on designs and material first supplied by Khan. At one meeting it is said Khan's representatives basically offered a menu with a price list attached from which the Iranians could order.

Khan also made more than a dozen visits to North Korea where nuclear technology was believed to have been exchanged for expertise on missile technology.

In all these cases, the big unanswered question was the extent to which Khan was acting alone, or working on behalf of the Pakistani authorities. Khan himself was reluctant to discuss these issues and takes many of the secrets relating to his clandestine activities to the grave.

Khan’s proliferation activities were eventually wound up in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, when his network came under intense scrutiny from Western intelligence. Matters came to a head when a team of American and British intelligence officers visited Libya in 2003 to persuade Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi to give up his efforts to acquire nuclear weapons. As part of the deal, the Libyans handed over a stack of half a dozen brown envelopes, containing Khan’s blueprint for building a nuclear weapon.

Under pressure from the Bush administration, which feared extremist terrorist groups like Al Qaeda acquiring nuclear known-how, the Pakistani authorities placed Khan under house arrest, even forcing him to make a televised confession.

Nevertheless, Khan remained a widely respected figure among Pakistanis, with streets, schools and even cricket teams named after him. Having become extremely wealthy he was also generous, funding a community centre near his home in Islamabad.