Between us, we have about four decades of commencements under our belts, which amounts to a lot of Pomp and Circumstance. Over the years, the ceremonies start to blur together: proud families snapping photos, faculty in medieval-looking robes and funny hats, teary-eyed graduates hugging one another and hours of speeches.

But even to our jaded eyes, the commencement ceremonies at NYU Abu Dhabi’s new Saadiyat Campus last weekend felt special. The students marching across the stage to receive their diplomas were the first to graduate from NYUAD. These students helped to create the institution from which they were now graduating.

Much has been made about the global nature of this graduating class, and indeed the list of names as they were called out sounded like a roll call at the United Nations. On the walls of the admissions office at NYUAD hangs a map with a pin in the country of every student. A string links the “home pin” with the NYUAD pin: the strings form a web that spans the entire globe. As one student put it, those lines mean “knowing people on both sides of almost every violent conflict around the world”.

What people may not know about the students at NYUAD, however, is that many of them are the first in their families to attend a four-year college, and that equally as many would not have been able to attend college at all without the financial aid that NYUAD offers – aid that is need-based and nationality-blind. When people talk about the diversity of NYUAD’s students, then they would do well to remember it extends beyond nationality, ethnicity and religion. It also includes economic and class diversity. We think this extraordinary diversity offers our students unparalleled opportunities to develop and expand what might be called a cosmopolitan consciousness: a willingness to see difference as an opportunity for exchange and growth, rather than as a threat.

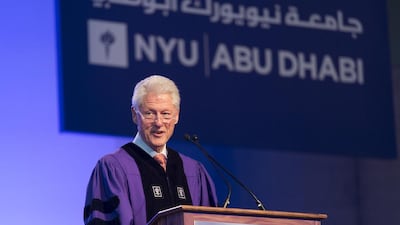

When Bill Clinton addressed these inaugural graduates, he used their diversity as the basis for a challenge. “We live in the most interdependent moment the world has ever known,” he said, and “defining the terms” of that interdependence will be the pressing task for this generation. He challenged the students to make the world’s interdependence look more like the way they’ve lived for the past four years: Indian and Pakistani students discussing genomics at breakfast, or Muslim and Christian students creating health education programmes for primary schools.

Mr Clinton’s speech mixed celebration with caution, however, because he addressed not only the signal achievements of the NYUAD students but also the allegations printed in The New York Times a few days earlier about mistreatment of construction workers on the Saadiyat campus construction site.

When work began in 2009, NYUAD, in conjunction with its Abu Dhabi partners, created a “statement of labour values” that amplifies and extends what is already codified by UAE laws. Companies working with NYUAD are contractually bound by this statement. The Times report accused the university and its partners of violating the standards established in the labour statement.

When the accusations of labour violations surfaced, both NYUAD and its local partners announced an immediate and transparent investigation. If the allegations are found to be true, violators will be punished and redress to the injured parties will be made.

We do not want to point fingers at the timing of the article’s publication – a few days prior to the NYUAD commencement – and we don’t want to argue about the statistics and accusations in the article, which to our eyes skirt the edges of sensationalism. And we admit to being curious about why the Times hasn’t responded to a letter, signed by more than 40 members of faculty and staff, which countered some of the claims in the article. Most of the faculty and students we know here welcome scrutiny about labour practices: what we find troubling are that these reports seem intent on finger-pointing rather than on an examination of the complexities of the task confronting NYUAD.

The NYUAD community – faculty, staff, administration and students – take seriously the idea of “community”, from the local to the global. Many of NYUAD’s graduates, for example, will be staying in the region to do social welfare and public policy work. Others are going to work with NGOs. Our students see, more clearly than many of the students whom we’ve taught in the United States, the ways in which the flow of migrant labour is problematic not just for the Gulf but for a world enmeshed in a system of global capitalism that measures profit only financially. Americans have wrestled for centuries with the question of migrant labour – stretching the term to include the several centuries of slaves whose labour built much of the US, including the nation’s capital and some of its major universities. To this day, the question of the migrant workforce in the US remains a vexed subject that has not been resolved to anyone’s satisfaction.

Bill Clinton told the graduates: “I wish the coverage this week had been about you: about who you are, where you’re from, what you’ve done – this astonishing experiment.” We agree, although there is something appropriate about these students’ graduating with a real-world reminder about the difficulty of putting cosmopolitan ideals into practice. Those difficulties notwithstanding, however, we believe that NYUAD students have both the ability and the desire to do just that. They will define the terms of interconnection in ways that open possibilities for all of us.

Deborah Lindsay Williams and Cyrus Patell are professors of literature at NYU Abu Dhabi