Even in times of widespread civil unrest, the border here has not been closed.

There is a sharp contrast between the scenes of violence in Iran and the strange calm at the Kapikoy crossing, tucked between snowy hills on the border with Turkey.

Dozens of Iranians used the crossing point on Friday, some seeking access to the internet in Turkey during a communications blackout in Iran that has cut it off from the world for more than a week.

Many were not willing to speak, and none wanted to be identified, amid a crackdown in Iran on protesters who flooded the streets over the past two weeks in the country’s widest civil unrest in more than a decade.

There has been no mass movement of people leaving Iran for Turkey despite weeks of unrest. Taxi and minibus drivers ferried people, wrapped up in thick coats in the minus 3°C temperature, to and from the border crossing point.

Protesters rally around the world to support Iranians - in pictures

But some travellers were willing to tell of their anger and frustration with the violent government response to the protests in Iran, even as they returned home. More than 2,600 people have been killed in protests that spread countrywide, according to human rights groups based outside the country. It is the highest death toll from demonstrations in Iran in recent years.

“People went out to protest innocently and were met with bullets,” one man told The National, as he crossed back into Iran. He and his family had come to Turkey for a few days to connect with relatives, before returning home.

Human rights groups have documented use of live fire and pellet guns against the protesters by government security forces. Asked why he thought this happened, the man said “the Islamic Republic does not want people to protest”.

Iranians were keen to distinguish between grievances with their government, and their love for the country, which has a highly diverse population and a rich history.

“We are happy with Iran, but not with our government,” another man from Tehran said, as he complained of deep economic suffering. The protests, which began in late December, were sparked by a sharp drop in the value of the Iranian rial versus the US dollar, compounding years of economic turmoil that have curbed Iranians’ spending power.

“Ninety per cent of people are not happy with the economy,” said the man, who arrived in Turkey on holiday three days ago and was now heading home. He added that Iran, with its vast oil and gas reserves, could be like crude-rich Saudi Arabia.

He was hopeful that the government would introduce economic reforms to improve people’s living conditions, but opposed talk of US intervention to spark a change. US President Donald Trump has threatened strikes on the country in recent days, although neighbouring countries including Turkey have been pushing for dialogue rather than military action.

“I don’t like Trump, I like my own country,” the man said, his head wrapped in earmuffs.

Iranian officials have blamed the deaths over the past two weeks on “armed terrorists” and framed the unrest as a US-Israel plot designed to weaken Iran. Some at the border thought similarly.

“The protesters were given money by Israel to weaken Iran,” said one man from the city of Zanjan, who said he was heading to Istanbul for a holiday. He praised the security forces for calming what he described as “riots”. “Iran is peaceful now,” he said.

Even in normal times in Iran, many citizens cross the border for holidays in Van, a city on the edge of a mountain lake. Travel agents and bus companies in the city advertise sales in Farsi, and cafes provide menus in the language.

“Iranians mostly come in the summer. Sometimes they aren’t given permission to leave Iran at the border, so they can’t come,” a hotel worker in Van said.

Other Iranians live in the city: a messaging app group for Iranians in Van is full of people asking how they can contact their families back home, or desperately seeking an internet connection. Two women at the border said they had come to Turkey for only a day to use the internet, before returning home.

Some brought with them painful stories of their experiences during the protests.

One Iranian woman in Van told of a brother and cousin being treated at home for pellet gun wounds sustained during the protests, too scared to go to hospital in case they are pursued by government forces.

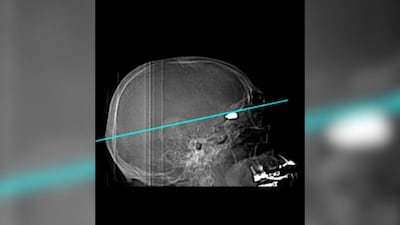

A family friend, who had been shot in the face with a pellet gun, a typical crowd control tool, went to hospital to seek treatment. There, he was detained by security forces and has not been heard from since, the woman said.

Her brother escaped much more serious injury because the men who shot him were aiming from a moving motorcycle, she said.

“Doctors have told him that he can stay like this for a while until all these things are behind us and he can see a neurosurgeon to take the pellets out of his neck and head,” she added. She sent The National a picture of the injury she sustained – a pellet gun wound to the leg that made walking painful.

The woman crossed to Turkey by land earlier this week to access the internet, vital for her work as an online tutor.

But she plans to return to Iran, unable to afford to stay any longer because of high inflation in Turkey that has pushed prices out of reach for an increasing number of Iranians. The collapse in Iranians' purchasing power was what sparked the protests, when traders closed their shops over a huge drop in the currency's value.

“Turkey used to be more affordable. I don't know, maybe I'm having some kind of halo effect over Turkey because a few years ago when I came here, I had good memories,” she said. “But this time that I came here, I couldn't find accommodation. I have to go back.”

She disputed the idea that protesters were Israeli and US-backed plotters, and that the demonstrators were responsible for killing others, as some Iranian officials have claimed. “This is absolutely false,” she said.

While Iran's government says the unrest has been brought under control, many Iranians believe their grievances over economic conditions and social and political restrictions have not been addressed, paving the way for more unrest.

Back at the border, one teenage girl returning to Iran from a European country with her family said “freedom,” when asked what she wanted for her country. “Freedom means living in a democratic country.”

The man who criticised the use of live fire against protesters said he had little hope for change while the current system of clerical rule is in place.

“Iranians have had to live like this for 40 years,” he said.