While Iran and the US are stealing the spotlight with talks set to continue on Saturday, this week belonged to Syria.

Over the past seven days, rivals and allies alike – including leaders and diplomats – have convened across the Middle East and beyond, all focused on shaping a future path for the war-ravaged country.

“Syria's future is the Middle East’s future,” said a regional UN diplomat who spoke to The National on the condition of anonymity.

“It’s the cornerstone of the region’s stability, and the new reality on the ground could open the door to a comprehensive peace,” added the diplomat.

For about a decade and a half, Syria under the Assad regime had been a source of deep concern for the Middle East and the wider international community.

What began as a crackdown on protests in 2011 quickly escalated into a brutal civil war. The regime’s violent suppression of dissent sent shockwaves across the region, displacing millions and destabilising neighbouring countries.

The country's descent into chaos provided fertile ground for extremist groups such as ISIS to emerge, exploiting the power vacuum and drawing in foreign fighters.

At the same time, the Assad regime’s deepening reliance on Iran, both politically and militarily, further inflamed regional tensions. Tehran’s influence in Damascus became a strategic foothold, allowing it to project power through proxy militias.

Adding to the alarm is Syria’s role in the production and smuggling of Captagon, which has fuelled black markets and addiction across the Arab world. The trade, reportedly run by regime-linked networks including members of Assad’s family, has become a key tool of both profit and leverage.

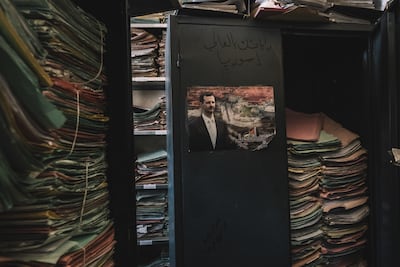

Beneath all of this lies a state shrouded in secrecy. The Assad regime’s refusal to allow international monitoring, its control of information and its manipulation of reconstruction aid have made accountability nearly impossible.

As a result, Syria has remained a black hole of governance, exporting instability, drugs and militancy while drawing in foreign powers and exacerbating regional divisions.

It all came to a head with the shocking rebel offensive in December. There were two major problems, though. The first was the sheer scale of the wreckage left behind by the former regime. The second was more complicated, as the new rulers included groups that had extremist elements within their ranks and had previously been affiliated with Al Qaeda.

Diplomatic marathon

Formerly known by the nom de guerre Abu Mohammed Al Jawlani, the new leader of the country, Ahmad Al Shara, fought for Al Qaeda in Iraq before eventually breaking from the group and creating his own militant faction.

Barbara Leaf, former US assistant secretary for near eastern affairs, was among the first western officials to meet Mr Al Shara after he came to power. She made it clear this week that the Syrian President must act fast to build confidence with the population and neighbouring countries.

“In the end, he’s going to be judged, I think, by how he responds to the many accumulating tests that lie out there,” Ms Leaf told a panel at the Sulaimani Forum in Iraq’s Sulaymaniyah.

During the same conference, Iraq’s Prime Minister Mohammed Shia Al Sudani told The National’s Editor-in-Chief Mina Al-Oraibi that his country has invited Mr Al Shara, who received the Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas in Damascus on Friday, to the Arab Summit scheduled in Baghdad next month.

Hours later, it was revealed that Mr Shara and Mr Al Sudani had held their first known meeting since the rebels seized control of Damascus and sparked fears in Iraq of a resurgence of extremism. The meeting, mediated by Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim, took place in Doha on Tuesday, an Iraqi government official told The National.

Mr Al Shara’s presence in Doha also coincided with a visit by Lebanese President Joseph Aoun, who has vowed to build relations with the new Syria and work on resolving the border tensions that have led to deadly clashes in recent months.

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El Sisi also visited Doha around the same time. Cairo viewed the replacement of President Bashar Al Assad’s regime by rebels with Islamist roots as a seismic shift in the Middle East’s geopolitical landscape.

The Syrian President was coming from a visit to the UAE, where President Sheikh Mohamed expressed his commitment to helping Syria rebuild. It was later announced that Syria's national carrier Syrian Air will resume direct flights to Dubai and Sharjah from Sunday.

Later, Sheikh Tamim delivered an olive branch from Syria to Russian President Vladimir Putin during a meeting in Moscow on Thursday. He told Mr Putin that the new leader in Damascus was “keen on building a relationship” with Russia, a major ally of the former Syrian regime.

The diplomatic marathon continued with Saudi Arabia’s Defence Minister Prince Khalid bin Salman visiting Tehran in a rare ministerial trip of this level to Iran. The statements mentioned regional developments, but it is undeniable that Syria was on the agenda, given Iran’s former role in the country.

On Monday, it was reported that Saudi Arabia is planning to pay off Syria's debts to the World Bank, paving the way for the approval of millions of dollars in grants for reconstruction and supporting the country's paralysed public sector.

To many experts, Syria’s challenges are the region’s challenges. If Syria fails, the consequences could further destabilise the Middle East. But if it succeeds, it may finally open the door to a new era of regional prosperity.

“It’s a pivotal moment,” affirmed the UN official.