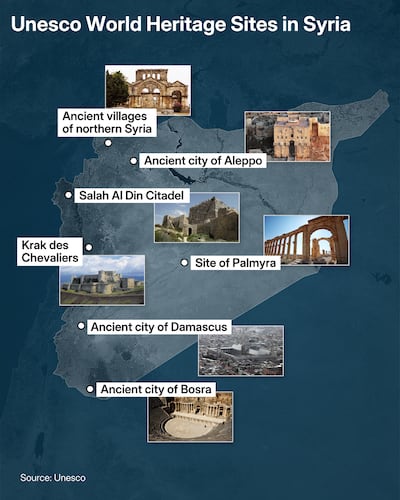

Before Syria's civil war, the fabled antique ruins of Palmyra were the country's top tourist destination, with around 150,000 visitors a month.

Now, the site stands as a shadow of its former self, its most iconic monuments, including a 2,000-year-old temple dedicated to the Mesopotamian god Bel, blown up a decade ago by ISIS.

What is the extent of the damage? How should it be rebuilt? How should recent atrocities, including the beheading of the 82-year old man responsible of the site's antiquities, be included in future exhibits?

Since the fall of the Assad regime last year, Syrian officials, archaeologists, international organisations and donors have been grappling with those questions.

Speaking to The National, they have all outlined a process expected to be long, expensive, and sensitive. For it to be successful, the local community − a small number of whom took part in recent looting of priceless antiquities − must be involved.

“Palmyra needs to breathe, honestly, and hopefully its soul will return. We must stand by her so that she remains standing,” said Anas Haj Zeidan, director of Syria's Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums, on the sidelines of a recent conference in Switzerland organised by the international fund Aliph, Unesco and the University of Lausanne.

All are aware of the power of attraction of the site, which has fascinated visitors for centuries. In the 1930s, British crime author Agatha Christie visited Palmyra with her archaeologist husband, Max Mallowan. She described “its slender creamy beauty rising up fantastically in the middle of hot sand” in her short book of autobiography and travel literature Come, Tell Me How You Live.

“It is lovely and fantastic and unbelievable, with all the theatrical implausibility of a dream. Courts and temples and ruined columns … I have never been able to decide what I really think of Palmyra,” she wrote.

Yet today, there are barely any locals left to cater to tourists as hotels and restaurants remain shut. According to Hasan Ali, Palmyra Museum director, some 80 per cent of houses were destroyed in the war, and there is little basic infrastructure, including water, electricity and the internet. Near the archaeological site, the Tadmur Municipality Building also lies in ruins. Mines have killed scores of civilians.

“People are reopening parts of hotels that were abandoned to help provide lodging to visitors, but these kinds of initiatives are rare,” Mr Ali said. “Hopefully, services will get better so that big projects can start in Palmyra.”

The site's rehabilitation over the next years is expected to cost “a huge sum”, Mr Haj Zeidan said, and take “six to seven years”. It's about Syria's “sense of belonging, memory and national identity”, he added.

Some 80,000 people have visited Palmyra since the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024, according to Mr Haj Zeidan, who said it was remarkably good considering the circumstances.

He hopes that the new authorities will succeed in dramatically increasing the number of visitors to more than a million non-Syrians a year. Asked whether foreigners might not be discouraged by sectarian massacres that have rocked the country this year, Mr Haj Zeidan said Syria was safe for them, pointing at the many recent diplomatic and economic delegation visits to the country.

“Also, Syria is full of people arriving from border crossings from Jordan or the Yabouz crossing from Lebanon or Bab Al Hawa in Turkey. These arrivals mean that Syria is safe,” he said.

Remembering tragedies

What tourists will be visiting is the next question that experts have yet to answer. No decision has been made yet about how to restore the site's famous ruins – if they are to be restored. There have been comparisons made with the rehabilitation of the museum of the Iraqi city of Mosul, which was also vandalised by ISIS. Damage caused by a crater bomb was purposefully left as a memory of events.

Emergency interventions will be needed after initial damage assessments are conducted, said Mr Ali, pointing at the gates of the Temple of Bel, which remain standing despite ISIS partially destroying the building with explosives in August 2015. “The focus needs to be on documenting what happened so that it can remind us of the tragedies that occurred in Palmyra or in Syria in general,” he said.

Overall, roughly less than half of Palmyra's heritage site, which lies across more than 16 square kilometres, was destroyed during the civil war, according to recent visitor Michel Chalhoub, an engineer who specialises in the restoration of built heritage.

Some structures, like the Arch of Triumph, were totally destroyed by ISIS explosives – a carefully choreographed destruction that horrified the world and became powerful symbols of Syria's civil war. In London, a 3D replica of the site was erected in Trafalgar square.

The Roman theatre, in which Russia organised an open-air classical concert in 2016, before Palmyra was taken again by ISIS, was only partially damaged.

The site also suffered from bombs falling from the sky as the Syrian regime battled for control over the area, destroying around 20 per cent of the 13th century Palmyra castle as well as the first floor of Palmyra museum.

'A place to heal the nation'

Additionally, more than 80 per cent of the 116 funerary structures on site have been damaged, mostly by looting, according to an initial assessment conducted by Lina Kutiefan, deputy director of the Syria General Directorate of Antiquities and Museums.

“Palmyra was once a famous trading city,” Ms Kutiefan in a speech at the Lausanne conference. “Now, it must be a sign of refusal to accept destruction. More deeply, it must be a place for healing the nation, helping to rebuild both the physical ruins and the spirit of the local people.”

Looting can be prevented by better co-operation with local communities, experts say. In his presentation, Japanese archeologist Kiyohide Saito said 11 bust-type sculptures were stolen from the south-east necropolis two years before ISIS invaded Palmyra, suggesting the theft was likely by locals.

Mr Saito was part of a team of Japanese archaeologists who worked on site for two decades, yet rarely engaged with locals.

In 2001, when they unearthed gold bracelets, necklaces and rings from the Hellenistic period − from 323 BC to 32 BC − rumours spread in the town about the archaeologists finding “a large nugget of gold,” he said. Today, the artefacts are missing from the Palmyra museum.

“We now deeply regret that the Japanese team failed to convey the importance of cultural heritage to the local population,” Mr Saito said. “We believe this very point lies at the heart of why looting became rampant amid the chaos of the conflict.”

Mr Ali, who is from Palmyra, said there is no denying that locals have taken part in looting, but believed this is not widespread.

“When the city was freed, a lot of people went directly to Palmyra Museum to monitor it and sleep there because there were afraid of looters,” he said.

“Most people understand that the stones are part of their heritage, culture and their identity. This is something we'll continue working on.”