For decades, Maha Al Daya was known in Gaza as a master embroiderer of traditional dresses, a vibrant tribute to Palestinian identity brought out at times of celebration.

But after fleeing the Gaza war, Ms Al Daya, 49, traded dresses for painted rubble and embroidered maps documenting the enclave's destruction. Gone are the flower motifs. Now, her work depicts ruins and displacement.

“Something changed inside me,” Ms Al Daya said. “I now only work on the pain and suffering I saw in Gaza.”

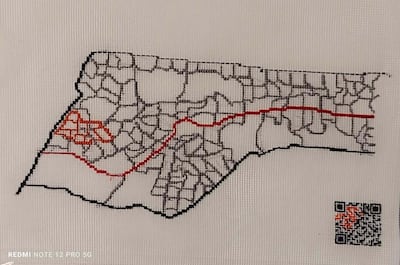

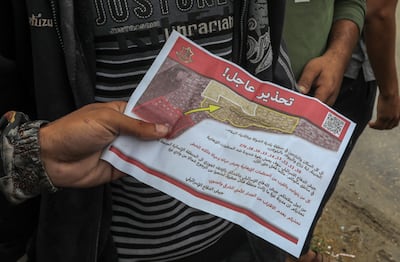

The geography of Gaza carries deep emotional weight for Ms Al Daya, as the maps reproduce leaflets thrown from Israeli planes telling Gazans to leave certain zones. The image of those fluttering papers falling from the sky remains seared in her mind.

In Paris, where Ms Al Daya has lived since January, she carries one of those leaflets taped to the back of her phone. When she met The National in her office, she wore a white T-shirt embroidered with “All eyes on Rafah”.

“It's the first time that my art is political,” she said. Her embroidery has even likely made it to the Elysee Palace. During a meeting in April at the Arab World Institute with French President Emmanuel Macron alongside other Palestinian figures residing in Paris, she handed him one of her maps of Gaza.

The red stitches conveyed its destruction. The black contour represented the sadness that now fills the enclave. She also gave him an embroidery on which she had stitched the words: “Where do we go now?".

“It's what all Gazans ask all the time,” she said. “Because there is nowhere for us to go.”

Tent refuge

More than 63,630 Gazans have been killed in Israel's retaliatory offensive after around 1,200 died in Hamas-led attacks in October, 2023.

After 23 months of war, which has caused mass starvation in the enclave, Israel now intends to occupy Gaza city, a decision that has caused an international outcry. In this context, France opened its doors to 24 Gazan artists and their families, including Ms Al Daya, via a state-run programme named Pause.

It supports artists and researchers from war-torn countries and gives them a year-long residency and a work contract at a prestigious institution. Ms Al Daya’s one-year placement, which is renewable, is hosted jointly by Sciences Po Paris and the Columbia Institute for Ideas and Imagination.

Her workspace, located in a large 18th-century building in the south of Paris, is just steps away from the studios of famed artists such as Amadeo Modigliani and Paul Gauguin. It opens on to a cobblestone courtyard and a lavender-scented garden.

“I yearn for quiet above all,” she said. “I can't stand the noise of planes any more.”

Life in Paris could not be more distant from what Ms Al Daya experienced with her family of four during six months of war in Gaza. Her emotions are a complex mix – gratitude for the chance to rebuild their lives, provide quality education and health care for her children, and a deep, persistent yearning for home.

“I do not feel like a stranger in this city, but I have a longing for my home and my city, Gaza, its sea and its streets,” she said.

When the conflict in Gaza started, the family fled their house with just a few items, thinking they would be back in days. Ms Al Daya's artwork, including dresses she had been working on for a fashion show, was left behind.

“We thought we’d be back in two days. The longest war had lasted 50 days in the past,” she said, referring to what Israel named Operation Protective Edge in 2014.

Unbearable conditions

But the house they sheltered in in Khan Younis was struck twice by missiles, injuring its inhabitants.

The family escaped unharmed but fled again to a tent encampment in Al Mawasi, an area in the south of Gaza where most of the enclave's population of two million is now living. There, they had to adapt to a life of squalor and overcrowding.

“What you see on TV doesn't begin to convey what life is like in Gaza. If I'd stayed, I would have died. I don't know how people continue to bear it,” she said. “I still have nightmares from that period.”

Her time in Al Mawasi was one of the hardest times in Ms Al Daya's life. But even then, she tried to embellish it with art. Using charcoal, she drew embroidery patterns on the tents, and even an imaginary bathroom, complete with a bathtub and a toilet.

“I dreamt of having a real bathroom,” she said. “We had to bring soap and Dettol and clean it for half an hour before using the neighbour's toilet because hundreds had used it before us.”

There was nowhere to shower, so the family washed with a water basin. Rain dripped through the tents. The neighbour's nine-year-old son died of hepatitis.

On the tents, Ms Al Daha also drew cacti – a symbol of steadfastness and pride, she said. At home, she had kept a cactus on her balcony, where she grew flowers.

In March 2024, the family paid $20,000 to an Egyptian travel company to leave Gaza. One month later, they left by bus. The sum was more than the family could afford. An artist in Bethlehem helped raise funds in exchange for future work by her and her husband, who is also an artist.

“When we passed the checkpoint, I felt I could finally breathe,” Ms Al Daya said. This kind of exit was made impossible for Gazans after Israel sealed the border in May 2024.

No going back

In Egypt, she applied for the Pause programme, supported by a French non-profit support network named Maan for Gaza. Nine months later, she arrived in Paris with her family.

Her sister, however, remains in Gaza. Every day, they speak on the phone. Each call brings grim updates of life in the enclave. Food and water have become scarce. A bag of coffee now costs 500 shekels, or $146, she said.

Paris is where the family's future lies, according to Ms Al Daya. She has a love story with the French capital, first struck when she went there for a four-month arts residency in 2012.

“Three times a week, I go to the Seine river to relax. Sometimes, I take my embroidery with me,” she said. “The war isn't over and even when it ends, Gaza will need at least 10 years to rebuild.”