Down a narrow alleyway in Iraq's ancient city of Najaf, amid sagging wooden balconies and turquoise-tiled edifices, people line up everyday at the doorstep of Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani with questions.

The answers he gives them may have played an important role at the street level in keeping the country out of all-out bloodshed as Syria's sectarian conflict spills over into Lebanon and Iraq.

Najaf, one of the two major seminaries in Shia Islam, has long insisted that religious clerics should not be directly involved in politics. This policy has helped the seminary, known as the hawza, to survive the most challenging of circumstances. It has also put Najaf at odds with its rival in the Iranian city of Qom, which is seen to act as a religious arm of the regime to exert broader influence in the region.

Today, the conciliatory stance of Najaf's clergy has been overshadowed by the fact that Shia militias fight against their Sunni counterparts in Iraq and Syria, turning the two countries into one battleground.

The recent confirmation by Hassan Nasrallah, who heads Lebanon's Shia militia group Hizbollah, that his followers were in fact fighting in Syria alongside Iraq's Mahdi Army and followers of Iran's Valeyat Al Faqih, has only deepened the schism between Najaf and Qom.

At the same time, the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant - an organisation linked to Al Qaeda - is gaining prominence in both Iraq and Syria, launching attacks on both sides of the border. Two weeks ago, the group claimed responsibility for attacks on Abu Ghraib prison that set free more than 250 prisoners, many of them were high-ranking members of the mother terrorist group. It was dubbed the biggest security failure Iraq has experienced since the withdrawal of US forces in 2011. The prison break prompted Interpol to issue a global alert that highlighted the extent to which Iraq's fragile security has been deteriorating.

The developments only confirm statements last month by the outgoing UN envoy to Iraq Martin Kobler, who said: "Iraq is the fault line between the Shia and the Sunni world and everything which happens in Syria, of course, has repercussions on the political landscape in Iraq."

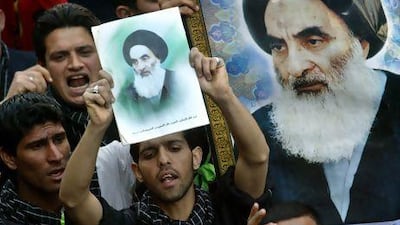

To be sure, sectarian attacks in Iraq are on the rise. July was the deadliest month this year, with more than 1,000 lives claimed in targeted bombings, shooting and killings. Najaf's Ayatollah Sistani, whose followers form around 60 per cent of Iraq's Shia population, has so far maintained consistency with his tradition of the Marja'aiya Al Samita (the quietist seminary).

To understand the reasons for Mr Sistani's aloofness from politics, one must review Najaf in the context of Iraq's history.

For as far back as three centuries, the seminary enjoyed a preeminent role in the religious and social spheres of Shia Islam. Its teachings have been conducted in Arabic, making the institution far more accessible to a larger audience than its counterpart in Qom which was perceived as foreign or Persian.

The two cities have experienced intense rivalry since the fall of the Ottoman empire. That tension has only strengthened following the Iranian revolution of 1979. But Qom swiftly ascended to the spotlight, replacing Najaf as the centre of Shia Islamic teaching. It was made possible after Saddam Hussein arrested Mr Sistani's predecessor, Ayatollah Abu Al Qasim Al Khoei, following a mass Shia uprising shortly after the first Gulf war. The event triggered an exodus of Shia and clerics to Qom.

Al Khoei died in 1992. He was replaced by his former student, Mr Sistani, whose decision to remove the seminary from politics proved to be a shield from Saddam in times of trouble.

But the tides changed for Qom after the 2003 US-led war on Iraq. With Saddam out of power, the exiled clerics left Iran for Najaf, helping the city quickly regain its prominence as the epicentre of the faith among Arab Shia.

The American-led war presented an enormous opportunity for empowering Iraq's Shia. Mr Sistani encouraged his followers to participate in the electoral process. However, he has been careful not to endorse a specific candidate for fear of tainting the image of the hawza should controversy erupt.

While he mostly sets out his views through envoys, he has spoken out on two occasions. His first was at the height of the sectarian war that took place from 2006 to 2008, when he tried to defuse vengeful killings based on identity. He told his followers that Sunnis are "ourselves, not (only) our brothers", in a bid to avert reprisals that could have destabilised Iraq. Had he remained silent, the results could have been far more disastrous.

The second, made more recently, was when he called on the prime minister, Nouri Al Maliki, to make concessions to the Sunnis and provide justice after a mass uprising in the province of Anbar.

But two weeks ago, gunmen executed 14 Shia lorry drivers. The gang checked the driver's identification cards, reminiscent of the darkest days of the sectarian war when people would be beheaded solely based on their religious affiliation and returned the heads in rubbish bags to their families. Local officials said the gunmen were associated with the Islamic State of Iraq, although the militia has not claimed responsibility for the killings.

Will Sunni-led calls for jihad against Shia in Syria, Iraq and Lebanon prompt the quietist Sistani to speak out once again?

It remains to be seen. The reality on the ground however, illustrates that Iraq's flimsy sectarian unity will not hold much longer.

On Twitter: @hadeelalsayegh