Venezuelan oil production could rise by up to 400,000 barrels per day, taking output to 1.2 million bpd by the end of 2026, if US sanctions are lifted following Washington’s capture of the country’s President Nicolas Maduro and its plans to oversee the energy sector, analytics firm Kpler said.

But output above 2 million bpd remains unlikely without deep reform and large-scale foreign investment, particularly from US oil companies.

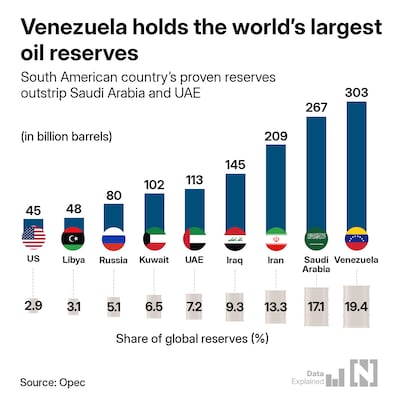

Kpler assumes current production in the Opec member, which holds the world's largest oil reserves, to be about 800,000 bpd – less than 1 per cent of global supplies.

If the US brokers a full political transition and offers complete sanctions relief, Venezuela could see a short-term increase in output between 100,000 and 150,000 bpd within three months, Kpler said. That would bring the country’s overall output closer to 1 million bpd.

The output increase hinges on a couple of developments, including the potential restart of the Petrocedeno upgrader, which converts Venezuelan heavy crude into lighter, more exportable grades. The heavy Merey grade, which is produced from the oil-rich Orinoco Belt, has specialised uses in refineries along the US Gulf coast.

A rebound in production will also be supported by workovers in the Maracaibo Basin, which is largely state-controlled, with Chevron operating through joint ventures with Venezuela’s PDVSA.

Supply growth is expected to slow after that initial increase. By the end of 2026, production capacity could rise to between 1.1 million and 1.2 million bpd, supported by mid-cycle investment and repairs at the Petropiar upgrader operated by Chevron, alongside further well interventions in western Venezuela, Kpler said.

A larger increase of 800,000 to 900,000 bpd by 2028, which would take production capacity to between 1.7 million and 1.8 million bpd, would need significant upstream capital spending.

It would require the restart of idled upgraders, including Petromonagas and Petro Roraima, in the Orinoco heavy oil belt in Anzoategui state, eastern Venezuela.

In the early 2000s, Venezuela produced closer to 3 million bpd. Caracas last produced more than 2 million bpd in 2017. Since then, years of underinvestment have left wells, pipelines, processing units and power systems in poor condition, particularly along the Orinoco Belt.

Without sweeping reform at PDVSA, as well as new upstream contracts signed with foreign operators, output of more than 2 million bpd is unlikely, Kpler said.

“Political uncertainty in Venezuela is extremely high, and it is genuinely unclear who can make binding economic or energy decisions,” Jorge Leon, head of geopolitical analysis at Rystad Energy, told The National.

“What does appear clear is that a rapid recovery in Venezuelan oil production in the short term is highly unlikely,” he added. Years of underinvestment and a depleted workforce mean rebuilding output would require significant time, capital and stability, with Rystad estimating around $110 billion in upstream investment needed to lift production from 1 million bpd to 2 million bpd by 2030.

Dubai-based Emirates NBD said in a note on Monday that the outlook for Venezuela’s oil production “remains highly uncertain”. The bank added that while developments in the country are unlikely to significantly affect overall oil market balances in the near term, specifically the first quarter of 2026, they could trigger localised market volatility.

Benchmark oil futures have shown "minimal response" to the events in Venezuela, with Brent opening down marginally on Monday at $60.60 per barrel and WTI trading at about $57.10 per barrel. Both benchmarks were slightly higher at 3.07pm UAE time.

Heavy crude market overhaul

While Venezuelan oil has been long dormant and under sanctions, its return to the markets would significantly reshape flows, particularly for heavy-sour barrels.

US Gulf Coast refiners are poised to absorb most of the additional heavy crude Merey volumes if sanctions are lifted. The region imported about 650,000 bpd of Venezuelan crude between 2013 and 2015, implying potential upside of about 500,000 bpd from current flows, Kpler said.

This would create a supply gap for Asia, particularly China, which has previously absorbed sanctioned Venezuelan oil.

China’s independent refiners, also known as teapots, imported about 400,000 bpd of Venezuelan crude in 2025. Cuba received around 16,000 bpd under politically driven arrangements.

Those volumes would decline sharply if PDVSA is asked to shift to commercial sales under US overview. India and Spain could import Venezuelan barrels again, with combined demand from both buyers expected to be about 100,000 to 150,000 bpd.

Venezuela’s repositioning in global oil markets could also support demand for other barrels in Asia that are under sanctions, particularly Russia’s Urals and Iran Heavy, which are likely to replace Venezuelan heavy-sour crude in the near term. Once supply from Caracas recovers, however, additional Venezuelan volumes would reintroduce competition, affecting rival grades.