The notion that a leader should have all the answers in a crisis is under serious re-examination, and some even view the idea as simply dangerous. It seems that, finally, the worst of the economic downturn may be over, both here in the GCC and around the world, at least if measures of business confidence are correct. According to the latest Global Snapshot, a quarterly survey of hiring and firing trends in 30 countries, 51 per cent of organisations in the UAE are hiring at managerial and professional level, up from 46 per cent last September , while 62 per cent expect to recruit over the coming quarter. At the same time only 24 per cent are shedding staff, and this figure is expected to drop to 23 per cent over the next three months.

But before we heave a collective sigh of relief, let's remember that the early stages of a recovery can sometimes be even more dangerous for businesses than a period of recession. This is the time when organisations start to lose their best talent as the jobs market frees up, when cash flow can run out of control and when theoretically sound businesses can find themselves in decidedly difficult circumstances. So what can the world's top management schools teach business leaders here to get them through these challenging times?

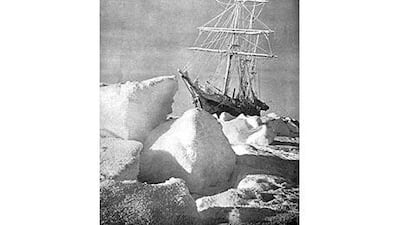

Marc Buelens, who teaches in the MBA programme at Vlerick Leuven Gent Management School, thinks the explorer Ernest Shackleton provides a model for managing under pressure and has built an extended case study to illustrate Shackleton's leadership style. "Shackleton's methods can teach you five key lessons a leader needs to perform effectively," he says. "Namely how to bring order and success to a chaotic environment, how to work with limited resources, how to let go of the past, how to keep troublemakers close and how to be self-sacrificing."

Other major schools are also using engaging ways to teach the art of leading under pressure. At Nyenrode business school, for example, new students on the MSc in Management are immersed in a "boot camp" where ex-marines show them the importance of being not just good leaders, but also good followers. And their contemporaries on the school's international MBA programme work with professional actors who role-play challenges they will be likely to face once back in the workplace. At the ESADE business school, participants in executive education programmes also take part in a theatre class focused on communication skills, which the school sees as key to effective leadership. The class goes as far as teaching techniques employed by stage actors such as controlled breathing, concentration and the use of facial expressions, silence and pauses.

Elsewhere, academics are challenging the very basis of what makes an effective leader in times of crisis and are shaping new models for those at the top of the commercial and banking world. The ESMT school in Germany surveyed more than 500 participants in leadership development programmes it ran for corporate clients and found a shockingly high proportion were attending not through any personal ambition but simply because their companies had sent them.

"A lot of people don't actually want to become a leader because of the high level of responsibility the role carries and because it can take them away from the technical aspects of their job that they have spent years mastering," says Konstantin Korotov, an associate professor at ESMT. "The problem is that there's often too much talk of leadership as in some way heroic. It's actually a very difficult and draining job, but if one is prepared for its negative aspects it can also be highly rewarding. What counts is that the individual understands what their strengths and weaknesses are and how to apply them to the role."

This criticism of the heroic model of leadership is mirrored in the work of the outspoken academic Henry Mintzberg, who teaches in the Desautels Faculty of Management at Canada's McGill University. "We don't need so much heroic leadership," he says. "What we need is what I like to call 'communityship'. We need to build up a sense of a community around the world. The problem is that banks and other corporations were managed by egocentrics who ran companies into the ground. Human resources were downsized at the drop of a share price. What a monumental failure of management."

However, perhaps the most radical approach in this time of transition is "adaptive leadership" as recommended by the international leadership development institute Mannaz. Jorgen Thorsell, the institute's vice president, says the old idea that a leader should have all the answers is not only unrealistic but potentially downright dangerous. "There needs to be an acceptance that a leader may be just as much in the dark as those around them," he says. "Instead, what they should be doing is bringing up difficult questions and then getting their team to experiment with solutions, moving forwards on a trial and error basis."

This, Mr Thorsell argues, is what strong leadership actually means in the 21st century. "It takes time to come up with the solution and, in the meantime, this approach can make it look as if the leader is not really doing anything. Take, for example, the first year of Barack Obama's presidency. He has given his people the time and space to confront enormously complex problems such as the economy and the US's role in Iraq and Afghanistan, but by doing this he has thrown himself open to accusations of inaction from his Republican opponents. Any CEO following the same line would need a very thick skin to achieve their objectives. But there is little doubt that if they have the courage to stay the course, the end result could be very impressive."

Matt Symonds is founder of SymondsGSB and a guest lecturer at business schools on inspiring leadership through storytelling. You can follow more of his business education coverage on his blog at http://symondsgsb.wordpress.com