Last year, we saw the first crisis of the new energy era. The most surprising thing about that crisis is arguably how limited its disruption has been. As the world turns the page on 2022, what is certain about this year is that the global push to decarbonise will not slow — it will accelerate, but with a new attention to security.

Previous energy crises centred on oil: the 1973 October War and embargo, the 1979-80 Iranian Revolution and Iran-Iraq War, and the First Gulf War in 1991. Each one of these involved a Middle East war, political upheaval and disruption of petroleum supplies. Today’s maelstrom centres on eastern Europe — gas and electricity are at its core, oil and coal whirling around the periphery.

The world oil market completely reconfigured from the early 1970s to the late 1980s.

From a closed oligopoly dominated by the western majors, who moved Middle East oil through their own refining and retail systems at administered pricing, it became a system where national oil corporations took over much of the production but sold into a complex, financialised ecosystem, whose prices were determined by the market.

Natural gas, coal, nuclear power and biofuels featured as potential replacements for oil. Modern renewable energy — wind and solar — were negligible. None were the centres of crises themselves, other than nuclear reactor accidents and domestic coal miners’ strikes.

Algeria tried unsuccessfully in the early 1980s to leverage its position as a gas exporter to Europe to extract better terms. That attempt was not successful and arguably damaged its own reputation. The Soviet Union and its successor Russia, by contrast, found ready gas buyers in Europeans seeking to get off Opec oil — Vienna, not Moscow, had them over a barrel.

The 1986 oil price crash hastened the Soviet Union’s fall; the price spike of the First Gulf War encouraged India’s then finance minister Manmohan Singh’s famous reforming budget of July 1991; and China’s economic transformation brought a long surge in commodity demand. The rise of shale in the US during the 2010s created a major non-state-controlled exporter of both oil and gas.

Globalisation created as close to a free market in oil as has ever existed; the gas business liberalised later, and less completely.

Modern politicians and energy executives grew up within this paradigm. Prices might rise at times, even to record levels as in 2008, individual actions of terrorist groups, rogue states, sanctions-happy US officials or hurricanes might cut supply in limited areas, and China might appear to be buying up oil assets globally. Countries in Africa and emerging Asia struggled to bring reliable energy to all their people.

But there was little real concern about the political availability of supply in aggregate. Instead, campaigners, voters and policymakers in Europe and, spasmodically, the US came to see energy as a subset of the problem of climate change.

This comfortable situation began to erode in the twenty-teens: China’s ban on supplying rare earth minerals to Japan, Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, an attempted US interdiction of Iranian oil exports followed by sanctions on Venezuela, and the general turn to “slowbalisation” with American suspicion of China.

Food price crises became more common and coincided with energy shocks; worries grew over the availability of critical minerals such as lithium and cobalt.

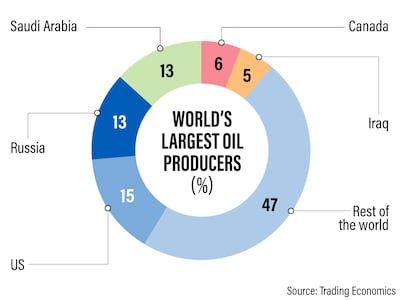

The formation of Opec+ in 2016 brought Moscow into the tent for the first time and concentrated more than 58 per cent of global oil output in one organisation, more than Opec alone had ever commanded. Last year, the US deployed its Strategic Petroleum Reserve directly and on a large scale to control prices, both on the upside and downside.

Weak investment in fossil fuels was driven more by low prices and poor shareholder returns than by environmentalist policies. Yet, seeing the green utopia on the horizon, governments failed to step up renewables, electric vehicles and improved energy efficiency fast enough to match the projected decline in oil, gas, coal and nuclear output.

The Covid-19 pandemic and the inflationary fiscal response then collided with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This is, on the face of it, a much bigger magnitude of geopolitical earthquake than the various Middle Eastern wars.

Russia, nuclear-armed and, at least in the Kremlin’s mind, a great power, accounted pre-war for about 13 per cent of global trade in oil, 18 per cent of coal, 20 per cent of wheat, and 24 per cent of gas. Moscow’s own near-halt in gas supplies to Europe, the G7’s own ban on importing Russian coal and oil, and the cap on the price of oil sold to other countries, are an unprecedented replumbing of the global energy market.

Yet the surprise is that the crisis in energy terms has been so muted. Weather, street discontent or bad decisions could still intervene, but for now, European gas and electricity prices have eased through a relatively mild winter.

At the end of 2022, oil prices were back where they started the year. Blackouts have been shuffled on to poorer countries in South Asia which could not afford to pay for liquefied natural gas (LNG).

State intervention has largely concentrated on supporting consumers rather than tinkering with domestic price controls, as happened with disastrous consequences in the 1970s.

There has been surprisingly little public unrest despite soaring bills and the danger of deindustrialisation.

The contours of the disrupted energy landscape are becoming a little clearer.

The globalised oil market of 1991-2021 is now being bifurcated - maybe later to be trifurcated or balkanised entirely. Already from March, oils of indistinguishable chemical composition had started trading with widely different prices and conditions and customers depending on origin

Moscow will attempt to turn its cumbersome gas system around 180 degrees to face East, but will achieve little success.

New Delhi, Beijing and Ankara will try to play at both tables. Opec, the major Gulf oil and LNG exporters, Asian refiners, and global traders all have some hard thinking about how permanent this reconfiguration will be, and how to react.

From Brussels to Beijing, the urgent hunt has begun for energy sources, storage systems and buffer stocks, interconnections and redundancy that are resilient to weather and geopolitics.

The multifaceted crisis that erupted in 2022 is spawning a more complex, more self-sufficient, less efficient and less predictable system - in which energy security is the imperative for all.

Robin M Mills is chief executive of Qamar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis