A vibrant urban park that celebrates the diversity of Copenhagen’s migrant communities, a think tank whose headquarters float above the historic precincts of the American University of Beirut and a Beijing children’s library whose concrete walls have been coloured with black Chinese ink are among the six winners who will share one of the world’s most prestigious architecture prizes.

The US$1 million Aga Khan Award for Architecture is awarded every three years to projects that are judged to set new standards of excellence while addressing the needs of communities in which Muslims or Islamic heritage have a significant presence.

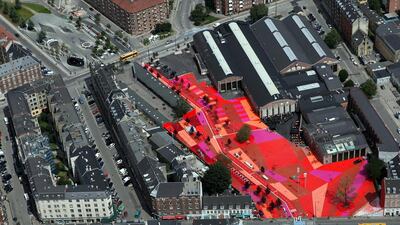

Selected by a master jury from 348 nominated projects, the winners of the Award's 2014-2016 cycle are: Superkilen, a 30,000 m2 park in Copenhagen, Denmark; the Bait Ur Rouf Mosque in Dhaka, Bangladesh; the Tabiat Pedestrian Bridge in Tehran, Iran; the Micro Yuan'er children's library and art centre in Beijing, China; the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon and a rural training centre built for an NGO, Friendship, in Gaibandha, Bangladesh.

The assessment, documentation, selection and judging process for each cycle takes three years, the Award has documented more than 9,000 building projects since it was established by the Aga Khan in 1977, and unusually for an award of its type the final prizes are given to projects as a whole and not simply to their architect.

“We see architecture as a collaboration between the architect, the client, the builders and the end users,” said Farrokh Derakhshani, the director of the award. “Each makes a contribution to the project’s achievement and it’s the combination of these contributions that make each of the projects an exemplar.”

Previous winners of the award have included the Azem Palace in Damascus, the National Assembly Building in Dhaka, the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris and the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur.

The announcement of the winners of the latest cycle, the 13th to have been awarded since 1980, was made at Al Ain’s Al Jahili Fort a full month ahead of the winner’s ceremony, which will be held at the historic monument in early November. Awaidha Murshed Al Marar, chairman of the Department of Municipal Affairs and Transport, was also in attendance.

In hosting the ceremony, Al Jahili joins an illustrious list of past venues that include the Alhambra in Granada, Spain, the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, the citadel of Aleppo in Syria and the 16th-century garden tomb of the Mughal emperor Humayun in Delhi.

As Mr Derakhshani explained, the decision to hold the ceremony in Al Ain was made in recognition of its unique history and status as Unesco World Heritage Site.

“The award ceremonies have always taken place in venues that have a significant position in the history of Islamic culture and now we are very lucky to be able to add Al Ain to that list,” the award’s director said.

“Al Ain is exceptional not just for its forts but also for its landscapes and I think that holding the ceremony here will help show the history of Al Ain and also of the region, which has played an important role that people may not be aware of.”

nleech@thenational.ae