Last week, Stephen King created something of a storm. It was not that King published yet another short story collection with a creepy title to coincide with Halloween – The Bazaar of Bad Dreams: Stories contributes to an oeuvre of hundreds of short stories and 50 novels – but that he put his name to a short story competition to publicise it. Published in the UK's Guardian newspaper, King promised to pick the winner from the best entries – of no more than 4,000 words, mind – inspired by this musing on the intrinsic joy of the short story: "There's something to be said for a shorter, more intense experience. It can be invigorating, sometimes even shocking, like a waltz with a stranger you will never see again, or a kiss in the dark, or a beautiful curio for sale at a street bazaar."

Somewhat self-evidently, King is a big fan of the short story form, yet only a few years ago he was bemoaning its demise. In 2007, he penned an article for The New York Times entitled 'What ails the short story?' and in it, he sounded amazed by how hard it was to find short stories in mainstream venues like bookshops and magazines, outside of The New Yorker and Harper's. "Once, in the days of the old Saturday Evening Post," he wrote, "short fiction was a stadium act; now it can barely fill a coffeehouse and often performs in the company of nothing more than an acoustic guitar and a mouth organ. If the stories felt airless, why not? When circulation falters, the air in the room gets stale." King had come to this anguished point of view while choosing the entries for 2007's The Best American Short Stories. The years in between appear to have seen a reversal in its popularity, however. Last month new story collections were released by several major writers: Ali Smith, John Connolly, Rachel Joyce, Alexander McCall Smith and Helen Simpson, and in the past year, Man Booker winners Margaret Atwood, Graham Swift and Hilary Mantel have all published collections.

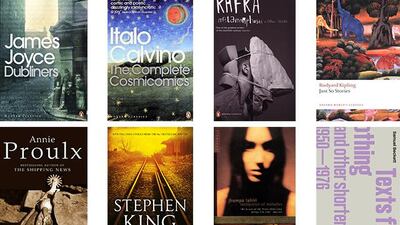

Philip Hensher has just edited the two-volume The Penguin Book of the British Short Story, while Ben Marcus did the honours across the Atlantic with New American Stories. Alice Munro struck a major blow for the form when she won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2013. A year later, George Saunders's Tenth of December beat several novels to the first Folio Prize.

The Arabic short story too is represented by two important anthologies. Daniel L. Newman and Ronak Husni edited Modern Arabic Short Stories: A Bilingual Reader, which featured work by Idwar Al Kharrat, Fuad Al Takarli, Layla Al Uthman and Nobel Prize-winner Naguib Mahfouz.

Salma Khadra Jayyusi's compilation, Classical Arabic Stories, begins in the pre-Islamic period, traces the form through the khabar and the maqamat, to Ibn Al Muqaffa's Kalila wa Dimna, Sa'di's The Gulistan from 1258, the seminal romance Sayf bin Dhi Yazan and the work of Badi' Al Zaman Al Hamadhani and Al Hariri of Basra.

Does all this activity mean that the short story is now in rude health? DJ Taylor, a novelist, critic, occasional short storyteller and contributor to The Review, tells me there is truth on both sides. "I suppose there is a bit of a resurgence, helped by various competitions, but there are still precious few proper venues in which stories can appear. Big publishers do fight shy of doing them, and when they do it's usually to oblige name authors. Literary editors don't help by allowing less space for reviews."

A major stumbling block for the reputation of the modern short story, like that of its siblings in concision – the essay and the poem, is the persistent predominance of that literary giant, the novel. Taylor recalls Kingsley Amis describing his own short fiction as “chips from the novelist’s work-bench”.Type the phrase “100 greatest books” into Google, six of the top 10 results automatically list “100 greatest novels”. Amis would doubtless say fair enough.

But just consider what these charts exclude. There are the incontestably great specialists in short-form prose. Representing America: Washington Irving, O. Henry, Dorothy Parker, Donald Barthelme, S.J. Perelman, Lydia Davis, Lorrie Moore, Raymond Carver, Tobias Wolff, George Saunders. Then we have Argentina’s Jorge Luis Borges, New Zealand’s Katherine Mansfield, Canada’s Alice Munro and Mavis Gallant, France’s Guy de Maupassant, Britain’s Saki and M.R. James, Syria’s Zakaria Tamer, Japan’s Yukio Mishima, Morocco’s Mohamed Zafzaf, and Iraq’s Mohammad Khodayyir, Egypt’s Yusuf Idris, Germany’s E.T.A. Hoffman and the Brothers Grimm. The chips from their work-benches and those of many other literary greats, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, Charles Dickens and Jhumpa Lahiri are too lengthy to list.

And I haven't even mentioned arguably the greatest and most influential story collection of them all: Alf Layla Wa Layla or 1,001 Nights. This anthology of folk tales from Asia and the Middle East, probably compiled from tales from the 8th to 10th centuries, contains an array of narrative forms and characters who have metamorphosed and appeared on the pages of countless authors since.

"Some stories belong in the category of al faraj ba'd al shidda, or relief after grief," the scholar Robert Irwin, who edited The Arabian Nights for Penguin Classics, tells me. "Others can be classified as belonging to the genre of aja'ib, or wonder literature, in which the reader is invited to marvel at all the wondrous things that God has created."

In narrative terms, 1,001 Nights creates a blueprint for the short story as offering a temporary release from the everyday. Scheherazade's deft manipulation of suspense, of tales within tales, creates a seemingly infinite imaginative universe that defies time and death, in her case literally. The foundation is a narrative concision that enthrals Sultan Shahryar without risking boredom.

Irwin says: “I think the best stories are of moderate length, say 10 or 20 pages. Certainly the saga of Umar bin Nu’man, the longest story in the Nights, is a dreadful ill-plotted shambles.”

Scheherazade's conviction about a story's ideal length compares favourably with Edgar Allan Poe's, written centuries later to explain the theories underpinning his wildly popular short poem The Raven, which was published in 1845: "If any literary work is too long to be read at one sitting, we must be content to dispense with the immensely important effect derivable from unity of impression ... if two sittings be required, the affairs of the world interfere, and every thing like totality is at once destroyed."

Bewitchment and escapism are not the only reward on offer in 1,001 Nights. Irwin argues that the book bridges a gap between an oral and a written tradition, which was intended to earn money. "Certainly some stories were recited in cafes, though it should be borne in mind that cafes only started appearing in the Middle East in the 16th century. It now seems that the stories were primarily aimed at literate lower middle class folk and chiefly circulated in copies that were lent out for a fee from the shops of scribes."

This direct relationship between art and commerce, identified by both King and Taylor, is fundamental to the development of the short story. Poe’s 19th century notion of short fiction was tailored to the publishing outlets that were springing up around him. Any history of short literature runs parallel to that of mass print culture.

All the great western novelists of the age (Dickens, Eliot, Flaubert, Chekhov) began by "writing for his [sic] life" as William Makepeace Thackeray put it in magazines and newspapers. Conan Doyle created Sherlock Holmes for The Strand Magazine, which also published early work by H. G. Wells and P. G. Wodehouse. Guy de Maupassant's enduring classic The Necklace provoked a national scandal after the Paris newspaper Le Gaulois published it in 1884. Washington Irving, who would became world famous for The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Rip Van Winkle, even founded his own literary magazine Salmagundi in 1807.

The unmistakably populist nature of these writers reflects the mass audience who read them. This grew large enough in the first three decades of the 20th century to make marquee authors like F. Scott Fitzgerald extremely wealthy. You can see how much from the accounts posted online by the University of South Carolina. An income of US$879 (Dh3,228) from “stories” in 1919 rose to $3,975 only a year later. In 1926, Fitzgerald earned $3,375 from just two pieces of work (as opposed to 10 in 1920). By 1931, he was earning $31,000 at $4,000 a story. When this well eventually dried up, hastened by the Great Depression, Fitzgerald mortgaged himself to Hollywood and depression of a different sort.

An alternative threat to the mainstream entertainments that Fitzgerald, Conan Doyle and Wodehouse wrote to order was Modernism. Short fiction was not exempt from the literary experiments of T. S. Eliot, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. "Prufrock is after all a short story," Katherine Mansfield said of Eliot's great poem. Mansfield's 1922 collection The Garden Party and Joyce's earlier Dubliners proposed fresh voices, approaches and subjects.

Revolutions in language, ideas of narrative, and psychological acuity challenged what David Gates calls the “Chekhovian template: modest deeds of modest people leading up to a modest epiphany”. Anything now could constitute a narrative. “I very recently met a man who said, how do you do. A splendid story,” noted Gertrude Stein, sounding eerily like today’s great miniaturist Lydia Davis. Modernism ensured that short stories would never be the same again, although according to Donald Barthelme, another of the form’s great innovators, it would take 40 years for this revolution to carry the day: “Fiction after Joyce seems to have devoted itself to propaganda,” he complained in 1964, “to short stories constructed mouse trap-like to supply, at the finish, a tiny insight typically having to do with innocence violated.”

The surrealism, challenging structures and formal innovations of Barthelme and John Barth inspired new generations. Lydia Davis's bibliographic joke, Index Entry, is a story in less than 50 characters: Christian, I'm not a. David Foster Wallace reimagined Barth's Lost in the Funhouse in his ode to self-consciousness, Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way.

The story gained new heights of artful playfulness and self-awareness but, according to Stephen King, lost something in the process. “[Such] stories felt show-offy rather than entertaining, self-important rather than interesting, guarded and self-conscious rather than gloriously open, and worst of all, written for editors and teachers rather than for readers.”

King’s despair can be explained by a broader cultural and economic shift. As the number of magazines willing to pay for fiction declined, creative writing courses ascended. Stories were no longer the preserve of popular periodicals, but the stuff of university courses. Popular authors stuck to the most profitable form – the novel – leaving the short field open to fledgling writers trying to find their voices. It would seem that the less writers were paid for short fiction, the more avant-garde those stories have become.

One antidote to – or in some cases extension of – these rarefied arenas are public events where stories of all sorts may thrive once more. Book festival and hot-house live readings, run by organisations like Pindrop, rewind to the very oral traditions that inspired the short story to begin with.

Competitions, as DJ Taylor noted earlier, also keep the story alive. Although in the introduction to the new The Penguin Book of the British Short Story, Hensher sounds sceptical whether this is a purely good thing. Dismissing Adam Johnson's triumph at The Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award worth £30,000 (Dh169,886) as "utterly routine", he argues that "the newspaper could develop any number of short story talents by, for instance, commissioning and running a short story every week for £1,000".

Taylor sympathises, but warns that financial reward is no guarantee of quality. “Orwell maintained, in the 1930s, that the low esteem in which the short story was then held was a consequence of how feeble many of them were. Certainly most popular writers of interwar period dashed them off to make pin money.”

Taylor sounds similarly unconvinced when I ask whether the internet and our oft-cited shortening attention spans might breathe new life into short forms. David Mitchell may have had fun composing The Right Sort on Twitter, but it doubled as a marketing exercise for a full-blown work, The Bone Clocks, itself a novel divided into six novellas.

Whatever the challenges, the short story endures as a precise but adaptable way to transform life into art. As Taylor tells me. “I like the short story because it is essentially an exercise in form, a splendid short-term challenge in which every word has to contribute and there is no room for padding.”

This pithiness remains the story's greatest strength, not just because it can hold the weakest of attentions but also respond quickly to the present in ways a novel's hefty demands cannot. Take last year's The Hidden Light of Objects, a short story collection by the promising Kuwaiti writer Mai Al Nakib which won the 2014 Edinburgh Festival's First Book Award. Covering everything from the invasion of Kuwait to the Palestine-Israeli conflict, her stories report from the frontlines of the Arab world today.

As Nakib herself writes: “... now look at us in our corner of the world, shattered in shards”. As long as there is life in shards, there will be short stories to describe them. Whether there will be readers paying attention is a question the rest of us must answer.

James Kidd is a freelance reviewer based in London.