Saul Austerlitz

It sounds like a fable: an independent-film producer approaches a studio with a project. It has two stars and a name director attached, and will cost US$20m (Dh73m) to produce. “After running the numbers,” Edward Jay Epstein tells us in his book The Hollywood Economist, “the studio estimated … its potential box-office in America at $100 million, which would yield it, just from its 30 per cent distribution fee and a locked-in output deal with HBO, a 100 per cent profit on its investment.”

Could mere mortals ask for better than an investment likely to return 100 per cent? Not so fast: “One of the studio’s top executives told the producer, ‘We don’t do films that do not have a projected box office of at least $150 million.’”

The effects of this only-in-Hollywood tale are to be felt everywhere in the contemporary film industry. Feverishly dedicated to the pursuit of jumbo-sized profit, the six major studios increasingly prefer to push their chips in only for the likes of Iron Man 3 or Battleship. The small- or medium-sized film is increasingly out of favour in today’s Hollywood, even its potential high-water profit margin is too insubstantial for multinational corporations in search of the next Avatar.

As Epstein amply documents in his book, and as the list of upcoming studio releases underscores – The Lego Movie and Stretch Armstrong are due in American cinemas early next year – the movies have become a playground for loud, splashy spectacles intended to get teenagers out of the house and into the multiplexes, where they will likely purchase large tubs of popcorn and jumbo-size Cokes. Only four genres, according to Epstein, are likely to be greenlit today by the studios: remakes, sequels, TV adaptations and video-game spinoffs.

In a recent speech that made the rounds online after it was printed in Film Comment magazine, Steven Soderbergh offered his own thoughts on the subject. Given his recently announced retirement from feature filmmaking, Soderbergh’s speech felt like an unburdening, detailing the financial and creative reasons for why films like his were increasingly unpopular among Hollywood decision makers.

In his example, a modestly budgeted $30 million film requires, in the studios’ estimation, $30 million in marketing and publicity costs to spread the word to a potential audience. Given that exhibitors retain 50 per cent of the box office receipts, that modestly budgeted $30 million picture suddenly requires $120 million to “get out” – to turn a profit.

Studios could spend money promoting small, personal projects by interesting filmmakers, or find an established commodity and ride it to international success. As Soderbergh notes, it is substantially more likely that a $100 million film, given $60 million of promotion, will gross $320 million than a $10 million film, given that same $60 million of promotion, will make $140 million. Mature, adult work, as a result, was now in danger of being permanently replaced by an endless stream of weightless, pointless movies: “A movie is something you see,” says Soderbergh, “and cinema is something that’s made.” And so instead of nurturing the next generation of Soderberghs, we get faceless, impersonal movies, and not cinema.

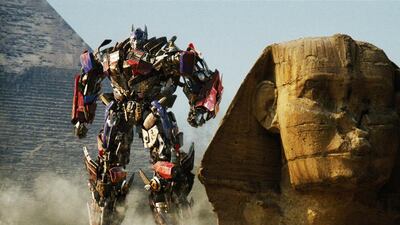

So where does this leave today’s A-list director? By this, I don’t mean the bankable likes of Michael Bay, overseer of the wildly successful Transformers franchise, or Steven Spielberg. Rather, what of the critically acclaimed filmmakers whose box office track record is mixed, or who prefer to scatter commercially unpromising projects amid more star-orientated vehicles? What of – horrors – the director whose non-superhero, non-science fiction stories could never dream of a projected box office of at least $150 million?

The fall of 2013 and spring of 2014 offers three potential paths for mid-career filmmakers in search of sustenance, both financial and creative. First, there is the Soderbergh model itself, mingling disparate projects, genres and price points. And who better to don the retired wizard’s mantle than his frequent collaborator and producing partner George Clooney? As a director, Clooney has shown the same polish as his mentor in films like Good Night, and Good Luck and The Ides of March, if without Soderbergh’s wild audacity in such indie efforts as Sex, Lies, and Videotape and Schizopolis. “George cut his teeth with Steven,” Matt Damon told me in a recent interview, “so he shoots each scene in a limited number of shots. He cuts in camera as he goes. As a result, he shoots fewer shots per day.”

Now, Clooney is helming his largest, most expensive effort yet, the Second World War art-heist drama The Monuments Men (recently pushed back to early 2014). Clooney has patiently modelled his directorial career on Soderbergh’s, using intelligent material, carefully selected performers, and a crew able to create the illusion of class on relatively threadbare budgets.

“Steven’s done nothing but be in one stage of production or another for 25 years,” Damon said in The Boston Globe. “He proved that he would come in on time and on budget for every single movie, whether it was a $1 million movie or a $100 million movie.” Clooney, like Soderbergh, has sought to make his own way in Hollywood as a filmmaker by drawing little attention to himself. Now he has reached his Ocean’s Eleven moment, whereby he will be judged by the studios – if only as a director. Can Clooney helm a lavish $100 million war epic and capably deliver an audience for a movie about American soldiers chasing down looted Nazi art? Or will Monuments only prove that Soderbergh had it right when he suggested that the studios now prefer to pool their money in less mature fare?

Not every director is given the option of selling out in the style to which they are accustomed. At the other end of the spectrum resides Spike Lee, who prefers to join them rather than fail to beat them. Lee has famously complained in the past about his difficulty financing some of his pet projects. Lamentably, he never could drum up the money to make his Jackie Robinson biopic, leaving the story about the baseball legend instead to Brian Helgeland’s 42.

Having achieved his best box office numbers with the twisty 2006 heist film Inside Man, which grossed $184 million worldwide, Lee returns to genre filmmaking with the upcoming Oldboy. Following Epstein’s dictum, Oldboy is a remake of a much-lauded film by South Korean director Park Chan-wook from 2003. Lee’s coping mechanism as a mid-career filmmaker is to sidestep his name. Oldboy, like Inside Man, is likely to appeal to a wide swath of moviegoers who may be only vaguely familiar with Malcolm X or Do the Right Thing. This is less “A Spike Lee Joint” than a big-budget horror film that happens, parenthetically, to be directed by Spike Lee.

Perhaps the least surprising, and the hardest, is to simply keep on making the same films. For 15 years, Alexander Payne has turned in wry, bittersweet stories about terribly flawed, yet likeable, people and the conundrums of the human condition, mostly set in the midwestern American metropolis of Omaha, Nebraska. Payne’s latest film, Nebraska, is practically a parody of the American art-house film, a Saturday Night Live sketch about obscurantist melancholia. But SNL vet Will Forte’s presence here is merely an extended dodge from the matters at hand. David Grant (Forte) drives the highways of Billings, Montana, searching for his peripatetic father Woody (Bruce Dern), who hopes to make it to Omaha to redeem the $1 million prize he received in the mail. That the prize is entirely imaginary goes without saying. Payne’s film is miserabilist, small-bore, dedicated to emotion over action. It is, in short, an exemplar of the American independent film, circa 2013, and marks out the farthest, least commercial end of the spectrum for established filmmakers.

Payne manages to work as he does by working efficiently in the Soderberghian fashion, keeping costs down, and most important of all, attracting name talent. “For a little more financing, and all that,” he recently told The New Yorker, “you have to write a screenplay that interests some actors. And if you can write a good part … that’s what you should do.” Nebraska cost $13 million to produce, pittance by contemporary studio standards; even his most expensive film, 2002’s About Schmidt, cost all of $32 million, primarily because of star Jack Nicholson.

Payne is revisiting territory already familiar from his About Schmidt, about another crotchety, ageing man pitted against the world. (Payne supposedly hoped to cast Jack Nicholson in Nebraska as well, turning to Dern when Nicholson unofficially retired.)

We can understand Woody’s quest as symbolic not only of Payne (who is neither ageing nor crotchety) but of many contemporary filmmakers, and for whom the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow – or in Omaha – is merely a chimera. Knowing there will likely be no payoff, Payne insists on making his way to Omaha nonetheless.

For some directors, the movies will always aspire to cinema, whether the studios understand it or not.

Saul Austerlitz is the author of the forthcoming Sitcom: A History in 24 Episodes from I Love Lucy to Community.