The cultural history of mid-20th-century Spain is often presented as a stark and simple series of events. In 1939 General Francisco Franco took power after a bloody, three-year civil war, and rapidly turned the country into a páramo intelectual (intellectual wasteland). Deviation from the fascist regime’s proscriptive ideas of national identity was robustly suppressed and many artists, writers and musicians were forced into either literal or internal exile. Then, in 1975, Franco died and his government fell. The subsequent transition to democracy ushered in long-denied freedoms and the creative currents of La Movida (the Scene) fuelled an artistic renaissance that continues to the present day.

This narrative is essentially accurate – particularly in the case of pop music, which struggled to exist in any meaningful sense throughout Franco’s time. But while the nationalist dictatorship tried its best to impose a totalitarian vision of cultural homogeneity upon the whole of Spain, communities from the Basque region to Andalusia refused to let their identities, traditions and art forms die. And, as a new compilation by the London-based label Soul Jazz reveals, the gitano (Romany) musicians of Catalonia managed to go a step farther than that.

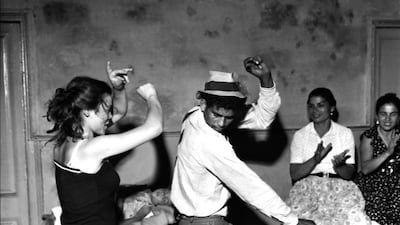

Gipsy Rhumba: The Original Rhythm of Gipsy Rhumba in Spain 1965-1974 is the first international release to concentrate on this largely under-appreciated seam of popular Spanish song. Curated by David García, the drummer of the Madrid indie-rock band Vetusta Morla, this 19-track compilation opens a window on a thrilling fusion of flamenco, Cuban dance music and rock 'n' roll that flourished in the Gràcia and Carre de la Cera neighbourhoods of Barcelona during this period. The album also comes with a fold-out booklet featuring copious sleeve notes (in English and Spanish) by Jose Manuel Gómez and a wonderful selection of archive photography by Jacques Leonard, a Frenchman who documented gitano life in Barcelona from the early 1950s to the mid 1970s.

As with many local scenes, the story of rumba Catalana is largely apocryphal. No one knows for sure when the style was first established or who was responsible for it. What is known is that it began as part of a wider phenomenon, known as “musica de ida y vuelta”. This name refers to the “return journey” to Spanish shores made in the late 19th century by a number of hybrid styles born in Latin America and the Caribbean. The songs were the fruit of cross-pollinations of flamenco – which had made its own journey across Spain from the gitano districts of Seville only a century earlier – and the musical cultures of African slave and/or indigenous populations in colonial territories.

The music that found its way back to Barcelona – possibly via Andalusia, which also developed its own early strain of rumba, but equally likely through the city’s own port – consisted of flamenco singing underpinned by Afro-Cuban clave rhythms. This fusion was quickly adopted by home-grown musicians, many of whom came from long-established Catalan-speaking Romany communities. Some enthusiasts believe that a similar palo (song structure) from the city of Lérida in western Catalonia, known as the garrotín, also influenced the Barcelona sound around this time. Either way, by the 1930s these elements had become so well assimilated that, while on a visit to the city, the poet and flamenco aficionado Federico García Lorca was driven to remark upon the difference between the traditional gitano music heard in his home province of Andalusia and the unique “swing” of its Catalan cousin.

Given the dire state of the Spanish music industry in the Franco era and the vernacular nature of the scene in question, no recorded document of rumba Catalana exists from before the 1960s. However, the style is widely considered to have come into its own in the late 1950s. Key to its development was a new method of guitar playing known as el ventilador (the fan), which allows the player to fingerpick the strings while simultaneously using the heel of the hand against the body of the instrument to provide percussion. Many say that the technique was pioneered by Pedro Pubill “Peret” Calaf – rumba Catalana’s biggest star. Others attribute it to Antonio González “El Pescaílla” Batista, while a few connoisseurs credit its invention to a little-known barroom entertainer named El Toqui many years earlier.

One thing that is indisputable is that this simple innovation forms the heartbeat of this music and, by 1963, was fully integrated into the style. That year Los Tarantos, a musical drama set in the gitano community of Barcelona and directed by Francisco Rovira Beleta, was released in cinemas. Starring the flamenco singer and dancer Carmen Amaya and the actor Daniel Martín as star-crossed lovers from feuding gipsy families, it proved a huge hit and went on to be nominated for an Academy Award in the Best Foreign Film category. It also provided a breakout moment for rumba Catalana, featuring Peret in several scenes, not to mention a cast of musicians that he personally helped to recruit.

Around this time, Franco’s government was trying to establish Spain as an international tourist destination. In order to achieve this, it was necessary to portray the nation as a modern, hospitable and fun place to be. Given its cosmopolitan roots (which could easily have been seen as a problem by the regime) and its apolitical, feel-good attitude, rumba was pragmatically and unofficially allowed to become the soundtrack of the era.

This is more or less the point that Gipsy Rhumba picks up from. The cohesive and tightly focused track selection attests to a musical movement that was by this point clearly defined, yet open enough to absorb a variety of contemporary influences. The raw and propulsive combination of voice, guitar, handclaps, bongos and güiro (notched gourds scraped with a stick) that formed the original sound is well represented by songs including Sarandonga by Antonio Gonzales and Los Gitanos Polinais's En el Fondo del Mar de Lima. However, the effect of rock 'n' roll upon the scene is also unmistakable.

In terms of instrumentation, the opening Nuestro Ayer by Rabbit Rumba modernises the pre-existing template by adding aggressive piano phrases and a throbbing electric bass line. Peret, on the other hand, keeps it simple on Voy Voy, but performs with the snake-hipped swagger of a young Elvis Presley. By far the most exciting moments from these years, however, come courtesy of Juncal y Sus Calistros, who serve up a blistering cover version of The Champs' 1958 hit Tequila, and Moncho y Su Wawanko Gitano, with the infectious, trumpet-driven Orisa.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s soul and funk were becoming increasingly popular in mainland Europe, and soon these transatlantic currents began to seep into rumba. Elements of both shine through the album's standout moment. The 1971 single Anana Hip shows why Dolores Vargas was nicknamed La Terremoto (The Earthquake), the singer delivering a devastating performance over a storm of wah-wah guitars, piano and brass. Vargas's second entry on the tracklist, A-Chi-Li-Pu, is rather more sedate but still hints at the dizzy heights her voice can reach. Meanwhile, on El Pan y los Dientes Chaco y Sus Rumbas take infectious Motown-inspired rhythms and steadily increase their pace until both singer and band collapse with exhaustion.

After all that, the album's final tracks – Maruja Garrido's Amaneci en Tus Brazos and Antonio Gonzales's Levantate – could be seen as tame and somewhat disappointing. Taken on their own merits, they are not at all, but perhaps most importantly, they draw a neat chronological line under this project.

In the early days of Spain’s democratic transition, rumba’s popularity plummeted. For many its sound was a reminder of a time they would rather have forgotten. However, this perception changed in the late 1970s, when musicians such as Gato Pérez reclaimed the genre by adding political commentary and a distinctly countercultural aesthetic. This rehabilitation set the stage not only for multi-million-selling bands such as the Gypsy Kings, but a brand new generation of performers. Now, as artists including La Troba Kung-Fú and Macaco bring elements of hip-hop, reggae, cumbia and pop to rumba Catalana and spread their work around the world via iTunes and YouTube, it seems like the perfect time for an album that takes listeners back to where this party started.

Dave Stelfox is a photographer and journalist. He lives in London.