Two hundred years on from her death and Jane Austen's immense popularity shows no sign of waning. She remains a publishing phenomenon, a cultural icon, a literary lodestar. Her six imperishable novels continue to enchant and delight legions of new admirers and faithful followers. "Every moment has its pleasures and its hope," Austen writes in Mansfield Park. Her work is studded with such moments. Little wonder that it has endured.

Over the past couple of decades we have witnessed a number of glossy big- and small-screen adaptations, along with various spoofs, spin-offs or reimagined updates by contemporary authors. However, the recent critical and creative trend seems to be to approach Austen from a different angle or tap into unexplored territory. Last year saw the release of Love & Friendship, a film version of the short, early, lesser work Lady Susan, starring Kate Beckinsale and Chloe Sevigny. A forthcoming TV adaptation of Pride and Prejudice promises to bring out the novel's "darker tones". This year, the British TV historian Lucy Worsley's Jane Austen at Home gave the reader access to the author's world through a tour of her houses, while Helena Kelly's literary history Jane Austen, the Secret Radical argued that beneath the soft-focus surface of Austen's comedies of manners lurk harsh realities and sinister subtexts.

A major summer exhibition at Oxford University's Bodleian Libraries took an equally fresh approach. Which Jane Austen? presented a rich selection of Austen material, from manuscripts to letters, books to artefacts, diaries to reviews, most of which prompt us to re-evaluate what we know about her.

The exhibition comprised sections covering each of Austen’s incarnations. “Teenage Wit” gathered together her favourite childhood fiction. The highlight, though, was not what she read but what she wrote.

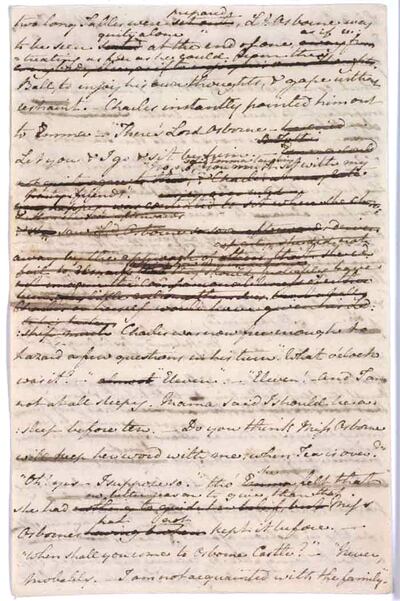

Austen was born into a family of enthusiastic amateur writers and, from the age of 12 to 18, she composed comic squibs, mini-plays and mock-didactic stories which she collected into three notebooks. One of them, entitled Volume the First, was on display. So too one of 18th-century England's "conduct" books, Elegant Extracts, whose contents ("for the Improvement of Young Persons") Austen lampooned in sketches about girls behaving badly.

Professor Kathryn Sutherland is the curator of the exhibition and editor of the fascinating companion book Jane Austen, Writer in the World. She is quick to disabuse me of the belief that this teenage writing is merely playful scribbling.

"I'd rather we think of the juvenilia as what they really are: the experiments of a teenager who is testing the limits of fiction and of female behaviour to find out what works, what's permitted, how far she dare go – in life and in writing. They are also exercises in how to write fiction," she says. "You can see traces of the feisty teenage heroines in the adult works – think of [Pride and Prejudice's] Elizabeth Bennet's wit and outspokenness."

As an adult, Austen had mixed fortunes as a professional writer. On show in Oxford: Austen's portable writing desk, given to her by her father in 1794, and taken by her when she travelled. Also, manuscript pages of two unfinished novels: The Watsons, which Austen began in 1804, at the beginning of her career; and Sanditon, which she started in 1817, at the end of her life. In one of many letters here to her sister Cassandra, 35-five-year-old Austen discusses working on, and constantly dwelling upon, her first published novel Sense and Sensibility: "I can no more forget it, than a mother can forget her sucking child."

Austen wrote novels and letters to family and friends at her desk, but also correspondence to her London publishers, including the renowned John Murray ("he is a Rogue of course, but a civil one"). Austen emerges as a canny negotiator. In one letter she pretends to be her banker brother Henry and makes clear her opinion of Murray's buying price for Emma: "The Terms you offer are so very inferior to what we had expected."

Of particular interest is a royalty cheque from Murray for the trifling sum of £38, 18 shillings and 1 penny, made out to “Miss Jane Austin” on October 21, 1816. (To put this in context, Sir Walter Scott, by far the bestselling novelist of the age, was making annual earnings of £10,000.) Rather than send the cheque back, pointing out the misspelling, Austen countersigned it with the same spelling, as if in a bid for quick, unimpeded payment.

The exhibition section entitled “London Shopper” hinted at a rarely glimpsed cosmopolitan side to Austen. A selection of letters written while on visits to the city describe many a “day of great doings”: shopping, tea-drinking and trips to the dentist, and in the evening musical parties and plays.

A replica of Austen's silk pelisse, or coat-dress, reveals more of what she might have worn. Its oak-leaf pattern symbolised Royal Navy oak ships, and was a patriotic design during the Napoleonic Wars. It wasn't cheap.

“It is best to think of it as the equivalent of buying a Vivienne Westwood or even a Chanel garment,” Sutherland explains. “It dates to around 1814 when Austen was gaining confidence in her ability to make money from her novels and wanted to splash out on a luxury item of clothing.”

The pelisse not only tells us that Austen indulged herself, it also provides her measurements: she was approximately 5 feet, 6 inches tall and, according to Sutherland, “thinner than Kate Moss”.

Elsewhere we found playbills and portraits, household recipe books and hand-copied music books. One section utilised posters and newspapers to chronicle Austen-family scandal. Other sections employed objects of a different kind in an attempt to dispel the age-old image of Austen as an author cocooned in a cosy, rarefied realm and deaf to the roar of public events. In “Wartime Writer” there were naval maps, logbooks and military treatises (of which Austen was an avid reader) on view; in “Progressive Thinker” I found documents and political cartoons relating to the slave trade. Excerpts from Austen’s books allowed visitors to decide how far these issues influenced her writing.

For all the array of objects on display, it was Austen's letters that dominate. Only 161 survive, all written with a standard goose quill pen. Most are lightweight, trivial and unedifying. The Bodleian Libraries exhibition singled out the most substantial letters. Few personal secrets are disclosed, but, as Sutherland outlines, we witness a range of tones, "from gossipy to confidential, witty to humorous and even cruel. Interestingly, in many of her letters to close family the voice hers comes closest to is that of Miss Bates, the village gossip in Emma."

In a letter to Cassandra from 1813, Austen sings the praises of “the first soldier I ever sighed for”. In 1814, she compliments her niece Anna on her literary efforts: “You are now collecting your People delightfully, getting them exactly into such a spot as is the delight of my life.” Perhaps Austen’s most poignant letter is one of her last, written in May 1817 while seriously ill. “I continue to get better,” she tells her nephew. “I am gaining strength very fast … Mr Lyford says he will cure me.” Within two months she was dead.

This exhibition underscored how Austen lives on and her remarkable trajectory: from being undervalued as a writer during her lifetime to gradually accruing posthumous fame, and finally to garnering an ever-growing band of fans and worshippers.

A final insightful section examined her 20th-century reappraisal and elevation to the status of cultural icon by way of an eclectic assortment of tributes. There were lavishly illustrated editions of her novels; testimonies from pilgrims who ventured into Hampshire in search of "Austen-land"; Rudyard Kipling's First World War short story The Janeites; and, half a century before the riotous film Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, a bizarre sci-fi take on Austen by Stella Gibbons irresistibly entitled Jane in Space.

_____________

Read more:

Adaptation and adaptability: Jane Austen beyond the page

The UAE Instagram account dedicated to celebrating literary inspiration

Taking a trip with reading in mind

_____________

Few novelists have so many devotees and imitators. And few continue to be read 200 years after their death. Sutherland attributes Austen’s lasting success to her innovation and ability to create intimacy. “She was the first novelist to explore characters from the inside,” she says, “to suggest that the novel can deal with thoughts and feelings at close quarters. She has the knack of convincing her readers that she writes directly for and to each one of us – that she is our friend.”

She is a friend who has proved largely elusive, frustratingly unknowable. An exhibition cannot fill in all the blanks but its objects and letters have helped to illuminate Austen’s world and force us to think about her life and her art in new and intriguing ways.

Jane Austen, Writer in the World by Kathryn Sutherland, published by the Bodleian Library, is out now