Kate Ascher is remembering the first time she stood at the bottom of the Burj Khalifa. "I couldn't even see the top of it because it was cloudy," she beams. "It was that enormous. And you know what? There were still another 50 storeys to build at the time ..."

Ascher tails off, as if she still can't quite believe the sheer magnitude of what was to become the tallest building in the world. And for someone who has just published a book detailing the anatomy of the skyscraper, it is refreshing to hear she is still as awestruck by tall buildings as she was the first time she set eyes on one.

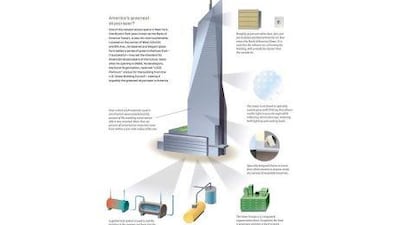

Her new book, The Heights: Anatomy of a Skyscraper, will surely take pride of place on the coffee tables of any right-minded apartment-dweller. Far from being a dry, academic treatise on why and how we're increasingly living our lives in the sky, it's a fascinating, endlessly entertaining tome, as comfortable telling us how tall buildings withstand wind as it is detailing the intricate history of tall buildings and their social impact.

It's also wonderfully illustrated by Design Language, making The Heights both easy to dip into and impossible to put down. And of course, because much of the recent tall-building boom has taken place right on the UAE's doorstep, it doesn't take long before Ascher's focus shifts from the US to the Middle East.

"That part of the world fascinated me because the skyscraper has begun to be used in a very different way from its traditional function as an office block," says Ascher, who is also a professor of urban development. "In the book, I mention that the Burj Khalifa is the world's first mixed-use building to hold the title of being the world's tallest structure, and it is interesting that, particularly in the Middle East, skyscrapers are places not just to work, but to live and play, too."

Such a development fits naturally with Ascher's thoughts on how we may live our lives in the cities of the future. She proposes that "vertical living", if managed correctly, can be wildly successful, environmentally friendly, diverse and, interestingly, community-focused.

But for Ascher, this is not a dream. It is already happening.

"Look, I live on the 11th floor of one building, and because it was designed well, I know my neighbours in the same way I would if I had a house on a street," she argues. "I used to work on the 44th floor. So skyscrapers are completely normal for me. They're just the world I live in. I mean, sometimes I am really awed by tall buildings. Other times, to be honest, I can be pretty turned off by one that looks ugly. But I'm always impressed by the effort that goes into designing and building a tall building - and most of all, making it work. The costs are so enormous, it's amazing that people have the confidence to build them."

The design of skyscrapers is something clearly close to Ascher's heart - and it's intriguing to compare, for example, the Art Deco majesty of the Chrysler Building in New York (Ascher's favourite) with the monolithic World Trade Center towers destroyed by Al Qaeda. But she also notices that, in Asia and particularly the Middle East, cultural references have begun to be incorporated into the buildings.

In the book, she cites the Al Bahr Towers, the future home of the Abu Dhabi Investment Council, as a classic example - the design concept derived from traditional Arabic patterns.

"It doesn't happen so much in the West," she says. "I wouldn't be able to tell you what made a building German, American or British. That's not necessarily a bad thing - the Shard in London would be a really lovely building, whatever country it was in. So I do think the idea of indigenous design is something that is currently unique to the Middle East and Asia, where there are strong cultural traditions. It certainly makes for interesting buildings."

But the paradox of The Heights is that it is not a book simply about the height of a building, nor even how a skyscraper might look. Ascher is just as interested in how a very tall building works once you're inside of it. Ever wondered where 160 storeys' worth of waste goes, or how the windows are kept clean? The Heights has the answers.

"I just want people to look around and understand their surroundings," she says. "It's important, I think, to appreciate all the invisible things that keep a building going because these places increasingly will be where a lot of people live and work. So, maybe, if more people understand them, the better these buildings will be."

A skyscraping ambition indeed.

The Heights: Anatomy of a Skyscraper (Penguin) is out now