It's tough to lament the death of Toni Morrison. I don't know whether the desolation is as a writer who will now never meet one of her biggest literary heroes; a reader who has spent over a decade hungrily drinking in every one of her words; or as a woman who lost and found herself within the pages that made up Morrison's rigorous stories.

Perhaps the best way to mourn her, is by remembering the way her words changed my life.

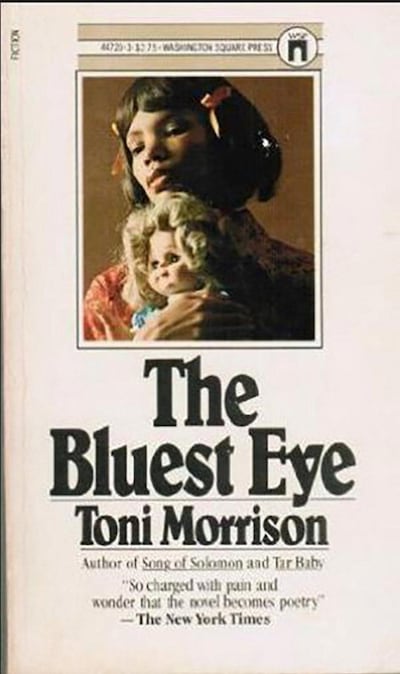

The Bluest Eye, Morrison's debut novel in 1970, may not be as popular as the Pulitzer-winning Beloved; but to me, it is her most intimate and special work to date. I've always thought of it as a literary hug from Morrison to all the broken, bruised girls of the world. It is a story that arrows straight to the heart of what we call family. Pecola, Claudia and Frieda are all young black girls; but while Pecola yearns to be accepted by the very people who exclude her, Claudia and Frieda's healthy sense of self-worth won't allow them to feel like they're lesser than. What makes one girl want to erase herself, while the other two independent and opinionated?

When I was a little girl, I was constantly being told how pretty I'd look — if only I could lose a few pounds or do something about my darker-than-usual skin. As a result, I spent much of my time wishing away the parts of me that weren't considered conventionally beautiful. If only there was a way to scrub my stubborn skin into submission and coerce it into appearing a few shades lighter. Maybe I could cajole my waist into being narrower if I ate one less meal a day. There wasn't, and I couldn't. I know because I tried.

I was 22 when I read The Bluest Eye, and Pecola's obsessive pining for blue eyes — convinced that they were the gateway out of her squalor and sadness of her life— made my stomach turn. Pecola's melancholy was my own. Like her, I had spent so much of my life wishing I was someone else. Mourning for Pecola and the insanity that finally takes her allowed me to grieve for the girl I could have been, but hadn't allowed myself to be. And for the many years worth of uncharitable words I assailed my younger self with.

Beloved and I were born the same year: 1987. I read it when I was 20, and it broke my heart in a million pieces. Through Sethe, a woman who so badly wants to protect her children that she decides to kill them, Morrison introduced me to the unseen, unknowable burdens that women carry. Can you love someone so much that you'd choose death over a life of persistent dehumanisation for them?

Beloved's protagonists are haunted and haunting, and I came away feeling both broken by and wiser to the forces that determine how people participate in life. I can't pretend to understand the horrors that run like charged undercurrents in the memories of Morrison's characters — memories of racial hatred; brutality in thought, word and deed; enslavement — but Beloved implored me to see, and to try and comprehend the violence of those memories. Once I did, it was impossible to unsee, or unknow them. It forever changed the way I interact with people who aren't "like me" and made me a better human being.

I read Sula when I was 19, and abandoned it halfway. I was compelled to return to it at 28, after being thoroughly captivated by Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels quartet. Together, Ferrante's Lenu and Lila and Morrison's Nel and Sula challenged my assumptions about morality and how we saddle our heroines — even fictional ones that exist only in our imaginations — with the responsibility to uphold them. Published in 1973, I read Sula in full 42 years later in 2015, and it felt like Nel and Sula were characters plucked from the world we currently inhabit. Tomorrow, we'll ruminate over the terrifying implications of a 42-year-old story feeling like it was written yesterday. But today, let's mourn Morrison by feeling her words. Like she said in her Nobel acceptance speech, language, after all, is the measure of our lives.