The world of poetry is booming. What was once seen as the preserve of elderly poet laureates and young dreamers has now aligned itself with the internet and is reaching new readers and markets. And distinct new voices are beginning to emerge.

In February, British newspaper The Guardian reported figures from industry bible Nielsen Books, which found that in 2012, poetry sales were at a low of £6.4 million (Dh30.3m). Yet, to the surprise of many, the Nielsen figures for 2018 show poetry sales hitting an all-time high of £12.3m – nearly double what they were in 2012.

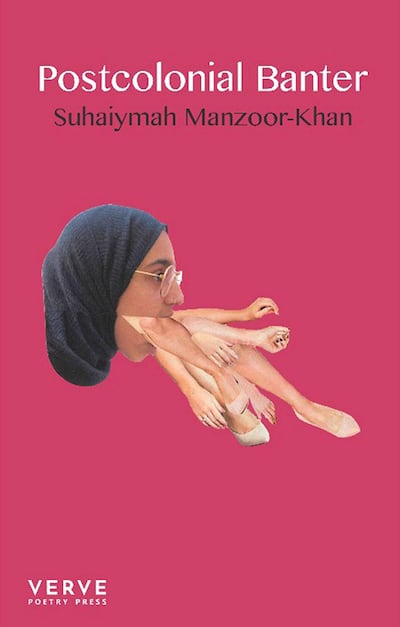

One poet who is riding on the crest of the UK poetry sales wave is Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan, 25, whose first poetry collection, Postcolonial Banter, was published by Verve Poetry Press in September.

Manzoor-Khan was born in Bradford to second-generation British-Pakistani parents. She was educated at the University of Cambridge and gained "a wider education from her mother and grandmother's pearls of wisdom" as well as "the epistemology of Islam and the work of women of colour", according to her blog The Brown Hijabi. She now lives in London.

Before getting her debut collection published, she built a substantial online presence via YouTube videos that deal with the complexities and arbitrariness of categories such as "young", "female" and "Muslim" in 21st-century Britain. A video of her performing This is Not a Humanising Poem at The Last Word Festival (an event designed for young and underrepresented poets in London's Roundhouse Theatre) has gained more than 83,000 views – with the line "Because if you need me to prove my humanity / I'm not the one that's not human", gaining rapturous applause from the audience.

Much of Manzoor-Khan's work online and in Postcolonial Banter pulls at the limitations of other people's judgment and the expectation to be Muslim, and what that means.

In 2017, she told TEDx Youth Birmingham that "everybody should be allowed and afforded the complexity that we afford to ourselves … we reduce other people to categories and binaries. [I want] to reject that there is a way to be a Muslim woman: that 'Muslim woman' refers to a monolith of people".

Postcolonial Banter presents a personal account of "identity" that runs counter to historical categories. It is "a mixture of very personal and very political expressions on the redistribution of knowledge and translations of feelings, but also a call to action", Manzoor-Khan tells The National.

The title of her collection is a deflation of the seriousness of politics and recognition of everyday experiences. "I chose Postcolonial Banter because when talking about violence, oppression, race, gender and class, it can be very overwhelming. But I also wanted to capture that it's mundane in many ways.

"When I was at university, my friends and I would call things banter that weren't. Like, 'did you see the news today, such-and-such really violent thing happened – oh well, guess it's just banter.' I think the title Postcolonial Banter was a way to mock the violence."

The term Postcolonial has been used to mean the cultural legacy of 18th and 19th-century colonialism in countries that were held as imperial possessions under countries such as Britain, France, Spain and Portugal. It is often also used to refer to books such as Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children, Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart and Mohsin Hamid's The Reluctant Fundamentalist, all of which were written as reflections on independence and cultural identity. Banter is British slang for light-hearted pranks or joking. And so, the title is both lighthearted and serious.

Many of the poems in Manzoor-Khan's collection combine the personal and the political, the violent and the everyday: in Where is my History? the official libraries of universities push against images of a typical British high street: "And my archives / are the chicken shops / the taxi stops / the backseats of rentals / and inside hems of headscarves."

In British Values, she deals with her unease with British society: "Britain is not listening / Britain is breaking / but breaking everywhere except the place it points the finger." She also plays against her clear love of the everyday details of diverse British life: "Britain is bismillah / Britain is basmati rice / Britain is box braids and black barbers' shops, Bollywood and bhangra Britain is Bradford and Barking and Birmingham."

These and many other poems in the collection are transcribed from Manzoor-Khan's live performances and it is perhaps wise to watch her perform before picking up her work – her emotional intensity and charismatic delivery can be missed when reading.

"There's something about speech as a form that I find particularly galvanising," she says, citing "political orators such as poet Audre Lorde, activist Malcolm X and writer James Baldwin" as formative influences on her spoken-word style.

That said, Postcolonial Banter also includes many new poems written specifically for the page. This is where her poetic ability displays itself to the full, although, Manzoor-Khan herself is sceptical about this division between spoken poetry and proper poetry. "What is page poetry and what is poetry?" she says. "If we saw a rapper getting down wouldn't that also be poetry?"

Two standout works specifically written for the collection are Nana and Nani, which mean grandfather and grandmother in Urdu. Manzoor-Khan uses these poems to reflect on the anxieties of migration and the poetic resonances of memory held by recent arrivals in Britain during the 20th century: "For secret home to escape in case when they send us back / the Asians were in Kenya eighty years she always says."

Thousands of former colonial subjects immigrated to the UK after the Second World War, particularly from India, Pakistan and the Caribbean. Many, such as Asian Kenyans, underwent double migrations, leaving Kenya after independence due to hostile legislation on the part of the new African government.

Manzoor-Khan's Postcolonial Banter uses the written form excellently to tell stories such as these. "I'm using Quranic storytelling – I'm working in an Islamic tradition – and storytelling is how you get messages across," she says.

This interest shows no signs of stopping, with reading figures soaring. In 2018, The American National Endowment for the Arts reported that 28 million people across the US were choosing to read poetry. Last year, US publication The Atlantic stated: "Social media seem to have cracked the walls around a field that has long been seen as highbrow, exclusive, esoteric, and ruled by tradition, opening it up for young poets with broad appeal, many of whom are women and people of colour."

This breakdown in exclusivity can be seen across publishing and the academic world in general. Last month, in the UK, On the 11th of October, the University of Cambridge's sociology department hosted Manzoor-Khan at the prestigious Pitt Building to talk about a collaborative project called The Fly Girl's Guide to Uni: Being a Woman of Colour at Cambridge. During the event, Postcolonial Banter was also promoted and available for purchase. However, the author still seems to side with the democratic reach the internet provides against more traditional channels of expression.

"Two people have read my dissertation and over two million people have watched a YouTube video of my poem," she says. She is positive about the future of poetry and the process of getting her first poetry book deal. "I think my favourite part of publishing has been realising that people will actually afford me the space to be a fully complex human being … that they're actually interested in poems about my grandma."