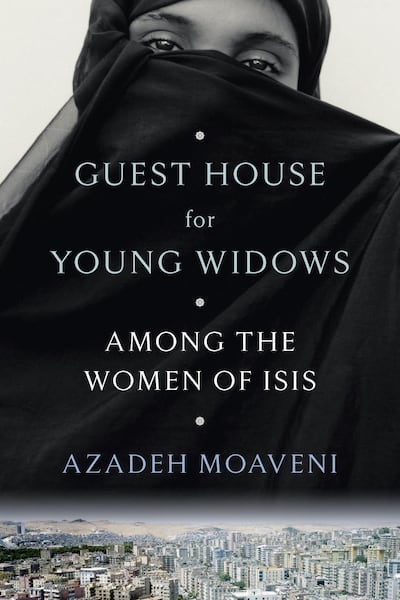

Azadeh Moaveni wants to challenge media narratives about women who joined ISIS. The American-Iranian journalist wrote her latest book, Guest House for Young Widows: Among the Women of ISIS, out of frustration at the way women recruited by the group, including the schoolgirls from London's Bethnal Green Academy, were reported on globally.

Moaveni, who lives in London, says the focus was often on religion and describes much of the reporting as lazy, saying it had a damaging effect on Muslim communities living in the West.

"I believe their race and religious background shaped the way they were treated by the media," she says. "The willingness to blame them even though they were clearly victims was distressing." The discussion of "victimhood" is captured in the book.

Moaveni spent almost five years speaking to more than 20 women who joined ISIS, as well as the families they left behind. The author was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize for a 2015 New York Times article she wrote about female ISIS defectors.

Her goal for her latest piece of work is to improve people's understanding of why a young woman would choose to travel to a war zone and be married off to someone she had never met who was fighting for a group known for its barbarism.

The book focuses on the stories of women and girls from the UK, Germany and Tunisia, as well as the accounts of recruits from Syria.

One of Moaveni's interviews was with Mohammad Uddin, whose daughter, Sharmeena Begum, was the first student from London's Bethnal Green Academy to travel through Turkey to Syria to join ISIS. In Sharmeena's story, the author argues that UK authorities did not take adequate measures to warn the parents of the teenager's three school friends, who also joined ISIS.

Sharmeena left for Syria in December 2014, two months before Kadiza Sultana, Amira Abase and Shamima Begum (who is no relation to Sharmeena) made the journey. "Once Sharmeena went and everyone knew and no one told the parents of the other three, there's not much that one can conclude but that there were serious failings," Moaveni says.

British media said Sharmeena, who left for Syria only months after her mother died, was radicalised by people she met at the East London Mosque and was directed towards online ISIS recruiters.

Her father, who is from Bangladesh, worked long hours as a waiter at a restaurant and, while he had noticed his daughter was spending more time at the mosque, he said he believed her growing interest in her faith was simply due to grief over her mother's death. Uddin said he urged police to "keep an eye on" his daughter's friends after she left.

Moaveni meticulously studied the media coverage of the departures of Kadiza, Amira and Shamima, whose disappearances were immortalised by CCTV footage of the girls going through security scanners at London's Gatwick Airport. At first, the broad reaction was shock at how three teenagers could leave the country without being noticed. But, before long, the British tabloid press began its flood of coverage, dubbing the girls "Jihadi brides".

"I really felt for the parents. They were immigrant parents," says Moaveni. "Some of them didn't speak very good English and they had no idea how to navigate the UK social system and police, let alone the kind of media attention they were getting. Everything they did seemed to backfire. Amira Abase's father went on television holding her teddy bear and was mocked.

"They were covered as if they were part of [British radical preacher] Anjem Choudary's gang. They were covered as a domestic terrorism story, not young girls who needed safeguarding because they were being groomed."

Moaveni finished writing Guest House for Young Widows shortly before Shamima was discovered in Al Hol refugee camp in northern Syria by a journalist working for The Times. Before that, there had been no sign of her for four years.

Kadiza was killed in a Russian air strike in Raqqa in 2016, according to a lawyer for her family. Kadiza's sister said the teenager told her family she was disillusioned with her life under ISIS but was too scared to run away.

Sharmeena and Amira were last reported as being in Baghouz, ISIS's last enclave, which the group lost to the Syrian Democratic Forces in March. Shamima's reappearance as a heavily pregnant 19-year-old, having already lost two children, features in the epilogue.

While Moaveni did not meet Shamima, plenty of western journalists did, as her case quickly became politicised. In her first interview, Shamima said she wanted to return to the UK, but did not express regret about joining ISIS. She even said she was unfazed by seeing the head of an "enemy" soldier in a basket.

In subsequent interviews, she appeared more contrite, but newspaper editorials were opposed to the idea of the UK government allowing her to return. In February, Sajid Javid, who was UK home secretary at the time and had his eye on the race to become prime minister, stripped her of her UK citizenship, a decision she launched an appeal against this week.

"The British journalists held mini trials in front of the cameras," says Moaveni. "I think the pictures and media coverage sealed her fate and I've heard senior people in government say the same – not the UK government, but other governments.

“It is almost certainly the case that if she hadn’t spoken to the media, she may not be back home, but she probably would not have had her nationality stripped from her.”

Moaveni has visited refugee camps in Syria where female ISIS members are being held and says the only way justice can be served is if the women are brought back to their home countries to face trial. Given public and media revulsion in the UK towards Shamima's case, it remains difficult for politicians to call for their return. "There's no sympathy for these people publicly and nor should there really be," says Moaveni. "But the rule of law applies. Otherwise what is the point of having a rules-based system?"