When Mohsin Hamid was a young boy, he and his friends would often live outside of reality while playing games of make-believe.

“Multiple children enter this imaginative space together, pretending they are pirates or astronauts,” he says. “To me, my novels are very much like that — they are invitations to readers to enter into a magical space.”

As an acclaimed novelist, Hamid's imagination is now more sophisticated. In his first three novels, he enlisted his reader to participate in the pretence.

His 2000 debut, Moth Smoke, casts the audience as judge. In The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2007), his garrulous Pakistani protagonist routinely interrupts his dramatic monologue to speak directly to us, his American listener. And, in How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia (2013), which takes the form of a rags-to-riches self-help manual, the reader is the main character.

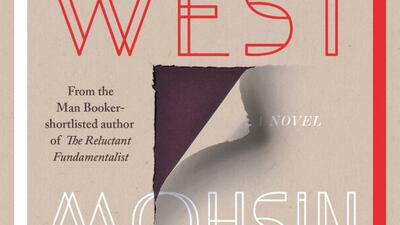

Recently, however, Hamid has taken more creative risks and enlarged that “magical space”. His last novel Exit West, which was shortlisted for the 2017 Booker Prize, follows Saeed and Nadia as they flee a war-torn city and search for sanctuary through a series of secret doors.

His enthralling new novel The Last White Man is a shrewd update of Franz Kafka’s 1915 novel The Metamorphosis. Anders wakes up one morning to find his skin has turned dark. While he waits for an “undoing”, he notices more and more people undergoing the same transformation and civil unrest erupting.

Speaking to The National from New York, Hamid explains he has become more interested in bending reality in his novels. “On the one hand, I believe that fiction is not real,” he says. “It’s this imagined experience co-created by readers and writers. The words from one are animated in the imagination of the other.

“But I think to a very large extent what we call reality is also not real. The potency of this unreal environment of fiction and the way that it can actually help us understand the unreal environment of what we call reality is what I play with.”

The Last White Man was a long time in the making. Hamid came up with the idea for it a year before the pandemic hit. But its real origins go even further back.

“I was thinking about my own experience after 9/11,” he says. “As a university-educated person who had a well-paying job and lived in large cosmopolitan cities like New York and London, I thought I had a kind of partial membership of this dominant group called whiteness.

“Then suddenly I became a member of this suspect class — being pulled out of lines in airports and stopped for hours at immigration, seeing people uncomfortable around me when I showed up on the subway or tube with my backpack. It was jarring, and initially I felt this profound sense of loss.

“That led to a cascade of thinking about people who feel their British-ness or their Muslim-ness or other elements of their identity are under threat of being taken away, and how it feels to lose those things — but also how it gives a possibility to reflect on something new.”

Hamid also derived inspiration from an unlikely source.

“There is a Sufi idea, which is that there are two different directions one takes towards enlightenment," he says. "One is that you look inside yourself and find the universe. The other, more transgressive strand says: look at the universe and find yourself reflected there. And, I think this sort of looking outside yourself and then discovering yourself in the process was something that appealed to me.

“I wanted to write a book about characters who weren’t, on the surface, me. I wanted to imagine people who were younger, older, and of a different racial background.”

Hamid describes himself as “a mongrelised, hybridised person”. He was born in Lahore, Pakistan, but has spent large parts of his life in the UK and the US. He once said he feels like “a half-outsider” in these places. Is this still the case?

“There’s still a little bit of land-sickness,” he says. “Like when you get off a ship you’ve been on for a long time, the land feels like it’s swaying.

“I can never quite slip into imagining that I can just see things from a British, American or Pakistani perspective. Not that those perspectives actually exist. I guess I’m always seeing the world from two or three different gazes at the same time.”

After years away, Hamid moved back to Lahore in 2009. Since then, he has written several illuminating, and at times excoriating, state-of-the-nation essays highlighting Pakistan’s lack of progress.

For Hamid, Pakistan continues to suffer from “profound pathologies”. He is still concerned about the country but is also worried about other places where he believes there are similar pathologies at work.

“You have this search for the strong man, the breakdown of the ability to come to democratic consensus, the inability of different political parties to work together,” he says.

“There is a sense of failure many people are feeling about their countries. It lends itself to a kind of nostalgic politics, which is often quite monstrous.

“People imagine that in America there is something unique going on with the rise of xenophobia and nativism. But there are similar currents in Pakistani politics, not to mention British, Turkish, Indian, Brazilian and Russian politics.

“The rise of these figures that are talking about the true people, the real citizen. A kind of sorting mechanism where we decide who is like us, and how we become quite confrontational to those who are not like us. This is personally troubling. A world of fetishised tribal purities is not a world that is particularly hospitable to people like me.

“And so,” he says, “I wanted to write a book that dealt with that.”

Mohsin Hamid’s The Last White Man was released on Tuesday in the US and will be out on August 11 in the UK.