Growing up, I faced racism every day. I grew up in a Paris suburb and there were only a couple of other Arab children at school. "Why don't you wear the Sphinx on your head today?" they'd taunt, along with comparable xenophobic remarks. I became involved in civil rights and that's why my film work is focused on these issues. It also connects me to my father because he was a man who always stood up against oppression and injustice.

My father left Egypt in 1956, the year of the Suez Canal crisis. He was sought after in Europe but didn’t want to stay in France or England at the time because both countries had joined Israel in attacking Egypt. He met my mother and they lived in Denmark before eventually moving to Paris in 1966, which was then a centre of the international art scene, especially for Arab artists. He always wanted to go back to Egypt, but the call to return never came.

In 1967, when I was 7 years old, my father completed a powerful, large-scale work that called for the downfall of Zionism. In June of that year, the Arabs were defeated in the Arab-Israeli conflict. Caught off guard, the Egyptians were struck by the might of the Israeli military, which subsequently destroyed almost all of the Egyptian air force. It was a major blow to the Arab world.

French media published a powerful image of shoes in the Sinai desert, presumably left by Egyptian soldiers. When I went to school the next day, 20 pupils had their shoes on their heads, and surrounded me, laughing. I was outnumbered, but I was wild and angry, and I fought back. I didn't run away. When I came home with torn clothes and bruises, I tried to hide from my father as I was afraid of his reaction. He found me, asked me what had happened, and when I nervously explained, he started to laugh. "I'm proud of you, my son," he said happily. "You saved the honour of the Arab people."

My father was the son of a farmer who came from the Said region of the Nile Valley in Upper Egypt between Luxor and Aswan known for its fertile land, crops and rich ancient Egyptian history. Because of this relationship with the earth, he was deeply affected by the idea of people being taken away from their land. I remember him saying, "If you have injustice in one part of the world, all of the world should be concerned." And that's why he considered what is happening to the Palestinians to be a global issue, one that troubled – or ought to trouble – all of humanity.

In 1968, he travelled to Beirut for an exhibition at Gallery One that presented 150 of his works. He gave 140 of those paintings to his friend, the Syrian poet Adonis, to store in his home. With conflict erupting in Lebanon, Adonis transferred the works to friends and left the country in 1975. Three years later, my father donated the works to the Palestine Liberation Organisation as part of a travelling show for a museum project for Palestine that was shown in Beirut in 1978 – a decade after they were first displayed in the Lebanese capital. He asked the PLO to take the works, only to find out that they had disappeared. There are letters between Adonis and my father that reveal bits of the tale, but many people involved in this story have died and we still don't know what happened to the pieces. That body of work fused form and text, and even though I couldn't read the paintings as a little boy, they were totally legible to me. I felt them and understood their meaning and their message.

I grew up watching my father paint all the time. It was part of my daily life and so natural, like breathing and eating. I could feel the gestures and movements, his swift brushstrokes and his fluid expression. The Arabic letters he painted almost became human. It was as though I lived among a society of characters that were very much a part of my universe. They influenced my perception of the world and of people and denoted all kinds of sentiments.

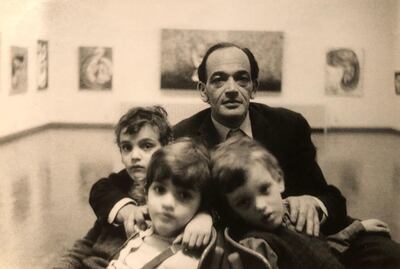

I remember being around intellectuals from all over the world who debated global issues. These were remarkably enlightening experiences. My father was very present in our education; he was a great teacher, was always happy to explain and took us to exhibitions.

My general knowledge about the history of art is owed to him and his research on masters such as Gaugin, Klee, Matisse and Kandinsky, who paid tribute to art from the East. Life as an Arab artist in France was difficult for him. A complex character, he came into conflict with both Zionists and other Arabs over the content of his work. He was a philosopher, painter, writer and mentor, and it is for these reasons and more that he was marginalised in the 1970s. But, he will be marginalised no more.

My siblings, mother and myself are all very involved in his legacy and our objective is to raise awareness about his work. There has recently been a resurgence of interest in Modern art from the Arab world and a school of art historians are looking at the postcolonial views of Arab art. The light is shining on my father's tremendous treasury – his work, philosophies and theories. Because he was a man of no compromises, perhaps this couldn't have happened when he was alive.

Hamed Abdalla’s painting Altamazoq is on display as part of the exhibition Taking Shape: Abstraction in Arab Art, 1950s-1980s at the Grey Art Gallery in New York until Saturday, April 4. Remembering the Artist is a monthly series that features artists from the region