One pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale is encouraging visitors to sit and read, even to daydream at their leisure, instead of pacing through on a high-speed marathon march.

This rest stop, among other things, is the pavilion of Finland in the city gardens, where several dozen other buildings representing the architecture of individual countries organise exhibitions every two years.

The pavilion is a modest structure of blue corrugated metal, across from the Netherlands and a few steps from Hungary. It is among the smallest of national pavilions in the garden. "It's really a kiosk," says Anni Vartola, the curator of its recently opened exhibition, Building Minds.

A space to stay for a while

This exhibition is devoted to the architecture of Finland's libraries. Those attending are invited to visit, but also to use the place as if it were a library. Seats designed by Finnish modernist master Alvar Aalto are spread around the space, where the history of Finnish library architecture is on view. There is at least one armchair, also designed by Aalto, with comfortable cushions where jet-lagged travellers could easily fall asleep. Wires are there for charging phones. The interior is in wood tones and soft grey fabric made of recycled peat fibres, giving the place the feel of natural warmth and monochromatic understatement.

"We wanted to create a space where you want to be for a while and charge yourself, to build your mind if you wish, as our title says, and also to be at peace and let things happen to you, to absorb them," says Hanna Harris, the organiser of the exhibition. "That's reflected in the exhibition architecture, as well."

150 years of history

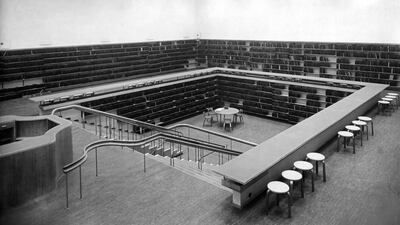

Those who follow the historical chronology along the walls will be taken through almost 150 years of library architecture. The journey begins with a Beaux-Arts palace of 1881, still functioning as a library, with an archive of art that borrowers can take home.

The journey around the inner walls culminates with models and renderings of the new Helsinki Central Library, also called Oodi – a massive structure with streamlined wood cladding and a rooftop terrace under what looks like a cloud. It sits across a downtown square from the nation’s parliament. Oodi, which means ode or epic poem, is due to open in December.

Harris expects 10,000 daily visitors to its three expansive levels once the doors open. Not all of them will be able to fit into Oodi’s sauna.

Finns take special pride in their civic buildings, says Harris, who is a daughter of an English father and a Finnish mother. She says that the firm that designed Oodi, ALA Architects of Helsinki, was chosen in a competition from 544 entrants.

“This is an important cultural structure, one of the most important we can have, for reasons of how it resonates in our city. And here we have a building being finalised when the exhibition takes place,” she says. It’s nothing if not timely.

'Libraries play a big role'

Given the broad theme of this year's biennale is "freespace", Harris saw her country's exhibition as "a generous gesture, as something that is free and open for everyone, which public libraries very much are".

Harris promises that visitors can also read books in the library show.

Some background for the project came from Jan Vapaavuori, the mayor of Helsinki and part of the team who opened Building Minds on May 24. A third of Oodi's €98 million (Dh421m) budget came from the city. Helsinki also funds another 37 libraries.

"We are a quite young nation in a European perspective, only 100 years old," he says. "We used to be a very poor nation, 100 years ago. We don't have any natural resources. The only resource we have is human capital.

"Some people saw 100 years ago that the only way ahead for a country like this is to go to its people and educate them as well as possible. "We don't have oil, so it's education, education, education – and libraries play a big role."

Aalto’s influence

If education has been at the core of Finland's "success story", as Vapaavuori calls it, Aalto has been at the core of its architecture. Aalto designed the Finnish pavilion in Venice, which opened in 1956. His style of unadorned modernism, as seen in a library he designed in 1940, identified him broadly as a great artist. (That library is now in Russia, after Finland's loss of territory after the Second World War, although Finns still restored it in 1970.) The backless wooden stools that Aalto designed offer places to sit for those who don't demand comfort. To sit in one of those stools for a long time, you have to really love Aalto or be extremely tired.

Pictures of Aalto buildings that were either renovated, repurposed or expanded by later Finnish architects are all over the walls.

Given Aalto's stature in a relatively small country – Finland has about 5.5 million people – the architect's influence has been inescapable for the generations that followed him, although some tried to rebel.

__________________

Read more:

Examining the UAE Pavilion at the Venice architecture biennale

Meet the Saudi architects making their debut at the Venice architecture biennale

A new project traces the history of the UAE's urban design

__________________

With Oodi about to open in December, Aalto's legacy has turned a corner, says Tommi Lindh of the Alvar Aalto Foundation, which oversees and advises on the preservation of his work.

"The new library," says Lindh, who was also in Venice, "is made by a new generation that is not afraid to copy something from Aalto. His contemporaries did not want to do it, and the ones who came after were too embarrassed to do it. The young generation has none of these inhibitions. They want to use Aalto as an inspiration and an influence."

Life after Aalto

Yet there is something new on the pavilion's walk through history. If a visitor can sit on Aalto's stools while escaping the Venetian sun, they can also relax on the soft peat fabric. "I was thinking of different qualities that make up the library space," says the exhibition designer and architect Tuomas Siitonen, another veteran of Aalto Renovations.

"I think everyone has memories of studying in a library and of someone hissing 'shh' when you happen to speak too loud. I wanted the Library Space in the Aalto pavilion [in Venice] to feel like a library, sound-wise.

"So I started looking for a sound-absorbing material that we could use to construct the exhibition architecture.

"I found a Finnish company called Konto who had a suitable product that was also sustainable and could be cut and printed on in the way we needed. To me, it presented innovation – they use a very traditional peat and make modern products out of it."

So there is life in Finnish libraries and the Finnish architecture after Aalto. Six months, the duration of the Biennale, will be a test of of durable that peat fabric is. As durable as Aalto's reputation? Now that would be a selling point.