A new exhibition, titled Picasso, the Figure, opens at Louvre Abu Dhabi today, offering a focused yet wide-ranging examination of the artist famed for reshaping how the human body could be seen, imagined and fractured in modern art.

Drawing primarily from the collection of the Musee National Picasso–Paris, the exhibition traces Pablo Picasso’s lifelong engagement with the figure, following its transformation across seven decades marked by formal experimentation, political upheaval and personal urgency.

At the heart of the exhibition is a clear assertion: Picasso was fundamentally a painter of the human figure, even when his work appeared to dismantle representation altogether. Throughout the 20th century, his art maintained a connection to the real, however tenuous that connection sometimes became.

The exhibition frames his practice as a sustained deconstruction of academic illusionism, driven by a desire to question and reformulate how bodies could be represented and expressed.

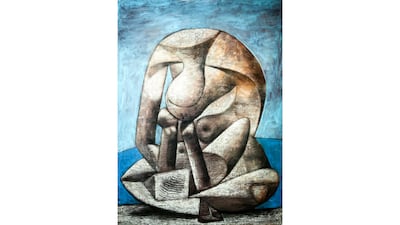

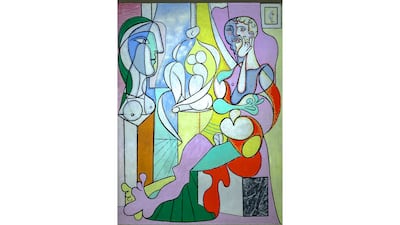

Rather than unfolding strictly chronologically, Picasso, the Figure is organised around a series of recurring gestures that shaped his approach to the body: schematisation through signs, incarnation, hybridisation, petrification and stylisation.

These thematic sections chart the evolution of his figures – from the hieratic symbols of Cubism to the monumental bodies of the 1920s, the hybrid beings of the Surrealist period, the fractured forms of the 1930s and the restless, urgent figures of his final years.

Speaking about Picasso’s artistic identity, Cecile Debray, president of the Musee National Picasso–Paris and curator of the exhibition, situates the artist within a broader European context shaped by displacement and cultural exchange. Picasso, she notes, was Spanish by birth, but lived most of his life in France. After the Spanish Civil War, he never returned permanently to Spain, a rupture that left him suspended between identities.

“He did not travel a lot,” Debray tells The National. “But he had a huge artistic culture.”

One journey, however, proved decisive. In 1917, Picasso travelled to Italy, where he encountered antiquity directly, including visits to Pompeii. The experience confronted him not with academic interpretations of classical art, but with its physical presence, leaving a lasting impression that would later inform his return to classicism in the years following the First World War.

This revival of figurative clarity is reflected in works that echo the delicate lines of French painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and draw on ancient marbles and frescoes Picasso admired during his time in Rome and Naples.

As the exhibition notes, this renewed engagement with the figure also responded to the trauma of war, offering a form of restoration in the aftermath of widespread destruction and bodily mutilation witnessed across Europe.

Elsewhere, the exhibition situates Picasso’s radical innovations within longer histories of image-making. One gallery draws on astronomy and mythology, recalling how the constellation Orion transformed a heroic figure into a network of stars. That fragmentation becomes a metaphor for Picasso’s own dismantling of the body.

From 1906, influenced by Iberian sculpture, Catalan Romanesque art and African and Oceanic objects encountered in Paris, Picasso developed a visual language defined by simplified forms and restricted palettes. These experiments culminated in Cubism and, by 1911–1912, in the near-total fragmentation of the figure into signs and planes, at times pushing legibility to its limits.

The question of Picasso’s enduring global stature is addressed directly. Debray describes it as “something amazing” that his name became shorthand for artistic greatness, pointing to the extraordinary variation, inventiveness and sheer volume of his output. Few artists, she argues, were as relentlessly prolific. But she also identifies two works as central to Picasso’s international reputation.

The first is Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), widely regarded as a foundational work of modern art and closely associated with New York’s Museum of Modern Art, where it came to symbolise the origins of modernism itself. The second is Guernica (1937), painted in response to the bombing of the Basque town during the Spanish Civil War. Conceived as a condemnation of violence, the monumental canvas evolved into an emblem of peace and the defence of civilians.

At Louvre Abu Dhabi, Guernica also becomes a point of connection with the Arab world. One section of the exhibition explores its lasting impact across the region, placing it in dialogue with Elegy to My Trapped City by Iraqi artist Dia Al Azzawi. Created as part of his Land of Darkness series following the Gulf War, Al Azzawi’s work adopts a similarly monumental scale and black-and-white palette, alongside dismembered bodies and animal imagery. Yet, it transforms Picasso’s visual language into a lament for Baghdad, where anguish prompted by destruction becomes both deeply personal and collectively shared.

This dialogue is reinforced by the inclusion of photographs taken by Dora Maar during the making of Guernica in Picasso’s Paris studio in 1937. Commissioned for the journal Cahiers d’art, the photographs document the painting’s evolution and reveal the physical constraints under which it was produced, including the need to tilt the vast canvas within a confined attic space. This gallery space is also accented with audio of poetry reading. The poem, read in Arabic, also titled Elegy to My Trapped City, is by Iraqi poet Abdul Wahab Al Bayati.

Myth remains a central framework throughout the exhibition. The Minotaur, a creature with the body of a man and the head of a bull, emerges as a recurring alter ego for Picasso, embodying both brutality and vulnerability. Metamorphosis, the exhibition argues, lies at the heart of his artistic vision, reflecting his belief in the plasticity of the human form.

Other myths, such as that of Deucalion and Pyrrha, who repopulated the Earth by casting stones that softened into human bodies, illuminate Picasso’s later engagement with sculpture, petrified forms and prehistoric idols.

The final galleries turn to Picasso’s late works, instantly recognisable for their double viewpoints, bold colours and dynamic lines. By this stage, Picasso had become a household name, enjoying a level of fame unprecedented for an avant-garde artist. Yet, these paintings are marked by urgency. As the exhibition text suggests, Picasso was racing against time, applying paint thickly and compulsively in a final effort to grasp the figure before it slipped away.

For Debray, the exhibition’s significance lies not only in its themes, but in the physical presence of the works themselves. Paintings, drawings and sculptures, she says, must be seen in person. Many of the works on display come directly from Picasso’s studios, including intimate and experimental pieces he kept throughout his life, alongside major paintings.

Together, they offer a rare opportunity to understand the human figure as Picasso’s most enduring obsession, and to see how its transformations continue to resonate in Abu Dhabi and across the wider region.

Picasso, The Figure runs until May 31 at Louvre Abu Dhabi