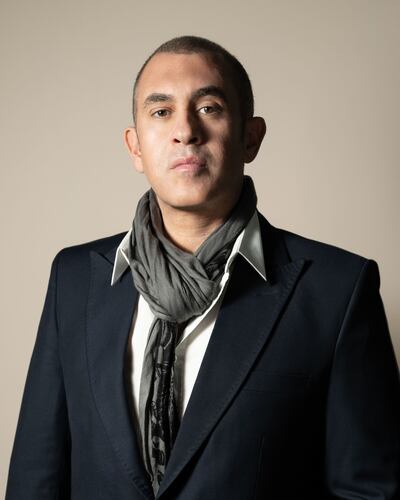

Omar Chakil may not be the first to carve objects out of Egyptian alabaster, but he is at the forefront of reintroducing the stone in a contemporary context.

The French designer, who has Lebanese and Egyptian roots, has become synonymous with the material, incorporating its mesmerising grains and yellowish lustre within cutting-edge concepts. His latest works do that as well. They also hold clues to the material’s historical significance.

Dubbed Transcendence, Chakil’s new series will be unveiled at Galerie Gastou’s booth during the Pad Paris art fair, which will be running between April 2 and 6 in the French capital. Some of the works hint at how the ancient Egyptians used their alabaster.

Canopic jars, for instance, allude to the vessels that they would make as offerings to their deities, or as containers for perfume and oil. Chakil’s jars are vibrantly coloured, making arresting decorative pieces.

Other pieces, meanwhile, draw inspiration from animals that had symbolic reverence in ancient Egypt. These include a chair with a towering backrest shaped like a cobra’s head, a coffee table decked with a scarab design, and a capsule bench imprinted with the swerving design of a crocodile’s tail.

Chakil says the series is a natural extension of Suite Anima, his 2022 exhibition in Egypt.

“Animism is the idea that an inanimate object can have a spirit or soul, which is what I feel when I see these objects that are made of a natural material that comes from the art of Egypt,” he tells The National. While his 2022 exhibition was inspired by this concept, Chakil says Transcendence was created to take the notion farther.

“People are actually realising that collectible design is design that transcends regular concepts,” he says. “The 10 pieces in Transcendence are handmade from blocks. They are the exact opposite of industrial production.”

Each of the pieces is the product of considerable research and craftsmanship. The Sobek bench is an example. Shaped like a capsule, the 300kg piece is predominantly made of Italian marble. The white and chalky material is juxtaposed with the yellowish hue of alabaster that forms the crocodile’s tail. “I took the tail of a Nile crocodile and scanned it,” Chakil says.

The design was inspired by a prompt from Victor Gastou, director of Galerie Gastou. “He wanted to make a piece that was inspired by the crocodile god of Egypt.”

The Uraesus chair also has an interesting historical aspect to it. “I did a chair that is like a cobra, but it's a birthing chair at the same time,” he says. Birthing chairs, which are designed to help a woman keep an upright posture during childbirth, are often thought of being a European design, Chakil says. “In reality, it came from Egypt. So, doing it in Egyptian alabaster, we're taking it back to its origin.”

Chakil’s newest series augments the designer’s mission of reflecting upon the history and heritage of Egyptian alabaster – a stone that was a favourite in ancient times, but fell from grace in the latter half of the 20th century.

“Egyptian alabaster was totally forgotten for a few decades,” he says. The designer attributes the declining popularity of the material to the trends prevalent during Gamal Abdel Nasser’s political ascendancy between the 1950s and 1970.

“Egypt closed in on itself,” he says. “The result of that, which is often the case, is that instead of celebrating the local materials, the rich people wanted to import stuff.”

Chakil adds that the wealthier classes opted to deck their homes in Iranian onyx and Italian alabaster, which has significantly different in properties from its Egyptian namesake. It is denser and white in colour, as opposed to the yellowish hue and softer nature of Egyptian alabaster.

Yet, Chakil says public opinion regarding the stone has greatly shifted since he began working with the material in 2018. “I didn’t discover Egyptian alabaster,” he says. “But I am absolutely sure that I brought it back into the sphere and now there is an interest for it beyond touristic artefacts.”

Chakil himself has become more in awe of the material, saying his reverence for the stone continues to grow. Its unpredictability, he says, has become less a point of frustration than a spur for creativity.

“It’s a calcite, so it has a lot of openings within it. Sometimes, you buy a big block and you want to do a piece with it. But when you open it, it breaks into two. There's a lot of different aspects in the stone that need to be considered,” he says. “But it’s a beautiful and really interesting material. There's always something you can do with it.

“It is really the stone of the desert. It has the yellowness and the spirit of the desert, and it comes from the desert,” he adds.