Every child grows up looking for a hero. In my formative years in Jordan, back in the 1980s, my earliest heroes were Superman, Spider-Man, the Japanese animated cartoon characters of Sasuki and Grendizer, and the complicated Long John Silver from Treasure Island.

All these characters were bigger-than-life figures who resonated with me on such a deep level that they have continued to affect me beyond my childhood, to this day, as an adult.

Childhood heroes influence who we become as grown-ups and, for the most part, our heroes come from television, films and books. Yet, interestingly, for some reason, none of my heroes were made in the Middle East.

Cut to 2010. I’m a filmmaker living in Los Angeles, having enjoyed a successful world tour with my first feature film, Captain Abu Raed, that I made in Jordan about an old airport janitor who becomes a hero to the children in his poor neighbourhood. Someone told me that Walt Disney International was looking for a director for an exciting new venture into the Middle East – an original Arabic live-action Disney film called The United, starring Arab actors, to be shot in the Middle East for distribution across the Arab world. Yes, I had the same surprised thought – “Disney wants to make an Arabic film?”

After convincing the executives at the Burbank headquarters that I was the right guy for the job, I was offered the chance to direct the first of three projects in development. The United would be a family-friendly football film about a group of kids from across the Arab world who come together to form a new academy built on the premise of Arab unity.

The film, written by LA-based Palestinian-American Nizar Wattad and produced by Rachel Gandin (who developed a deep love for Egypt after living there for a few years), would be the first time that any major Hollywood studio produced a film for this part of the world. It would be the beginning of a new chapter in the evolution of the budding cinema industry in the Middle East, with the backing of a large studio.

The question still was: “Why would Disney be interested in producing Arabic films?”

Following rising demand for regional content in Asia, the major studios had started experimenting with making “local language pictures” in markets such as India, China, and Russia. When Rachel Gandin approached Disney’s international productions division with her own personal dream, to inspire a new generation of Arab youth through the depiction of our very own stereotypes and heroes, Disney saw potential in a market of 300 million Arabs. The film was set in Cairo, with the members of the football team coming from across the Arab world.

As with every film, changes happen dynamically to suit the production’s limitations and available resources. In this case, for many reasons, we ended up moving the entire production to Jordan. We flew down to meet legendary Egyptian star Farouq El Fishawy, who agreed to play the lead, Coach Adli. We also cast Hollywood-based Palestinian actor Waleed Zuaiter as the man with the vision of Arab unity and the dream to build the Middle East Football Academy.

As for the young members of the “dream team”, we sent out casting calls using social-media tools such asFacebook, Twitter, and YouTube to set up Skype auditions across the Middle East and North Africa.

Finally, after two months of preproduction, we had completed our team, got them trained on the pitch, and rehearsed at the production offices while we found locations and built our crew. We were ready to start rolling film, just as the revolution in Egypt broke out and demonstrations across the Middle East kicked off.

Every step of turning this dream film into a reality would prove to be the most challenging experience of my life.

We filmed in January and February 2011, during the most uncertain time in recent Middle East history, in the middle of a freezing Amman winter, with a cast of first- time actors, none of whom were professional footballers.

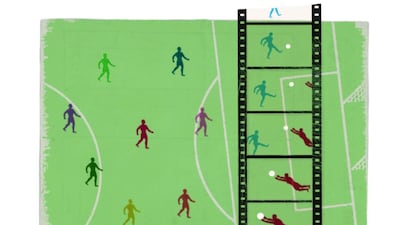

The making of the film was an adventure through a maze of daily surprises and challenges. Football, I would learn, due to the vast size of the field and the nature of its choreography, would be the most complicated sport to capture on film. We didn’t want to shoot the game from above, like a match on TV. We needed to get inside, on the field, with the characters, and resolve their story arcs in that final game.

The fields got wet and muddy and the budgetary constraints forced us to cut the shoot time from six weeks down to five (for the entire film). Every day was a new battle against the elements, and I can proudly say that we became one family, united, and despite some compromises, we ended up with a special film on our hands. The metaphor of the film had become a reality behind the scenes.

Unfortunately, for business reasons, Disney’s International division shut down and The United would be their last film in production. We’re lucky that we got the funds to complete it. But then the film sat on the shelf in London for two years – until now.

Finally, though it will not be released in cinemas, I am happy that The United is seeing the light of day. It was shown on OSN in the UAE yesterday, will be on Emirates and Qatar Airlines before the end of the year and has been sold to some 80 territories for an international TV release.

I recently sent out a message on the social media circuit to inquire who my fellow Arabs looked up to when they were growing up. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of the answers were similar to mine. Transformers, Ninja Turtles, Thundercats, Grendizer, Jongar, Sandy Bell, Abtal Almala’eb, Captain Planet, He-Man, Sasuki, Lady Oscar – all heroes made in the West or the Far East. Some also pointed out international sports stars, Pele, Maradona, Michael Jordan.

With The United, we set out to create new Arab heroes, young characters filled with both relatable flaws and big ambitious dreams. I hope that some kid in the Middle East today will look at these Arab boys and girl (Layla – the female lead who ties the team together) as their new heroes, characters made in the Middle East.

There will always be setbacks and bumps in the road when we set out for ambitious goals, but the most important thing is to keep dreaming big dreams, keep trying to build with a vision for the future, and despite all obstacles, to keep giving our youth new sources of hope and inspiration.

Yes, The United is just a small film, but to some boy or girl in the Arab world it could have a significant impact. Cinema is a weapon of progress, and I hope more Arabs will use it to create new heroes for tomorrow.

Amin Matalqa is a Los Angeles-based writer and director. His films include Sundance winner Captain Abu Raed, Disney International’s The United, and his latest American romantic comedy Strangely In Love.

Online: aminmatalqa.com