The discovery of the fossils of three ichthyosaurs in the Swiss Alps, including the largest tooth ever found for the species, has led to hopes that more evidence of the giant ocean dwelling reptiles will be found hidden in Europe's mountains.

They were uncovered at an altitude of 2,800 metres. During their lifetimes the three swam in waters around the supercontinent Pangaea — but due to plate tectonics and the folding of the Alps, the fossils kept rising.

“Maybe there are more of the giant sea creatures hidden beneath the glaciers,” said Martin Sander of the University of Bonn.

Earlier this year, it was announced that the largest fossilised remains of a prehistoric “sea dragon” have been found in the UK.

Scientists called the ichthyosaur discovery “unprecedented”, “highly significant” and one of Britain’s “greatest finds”.

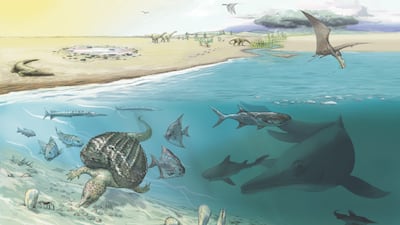

The size of a sperm whale at 20 metres and weighing 80 tonnes, ichthyosaurs patrolled primordial oceans more than 200 million years ago.

With elongated bodies and small heads, the prehistoric leviathans were among the largest animals to have ever lived.

They first appeared 250 million years ago in the early Triassic, and a smaller, dolphin-like subtype survived until 90 million years ago. But the gigantic ichthyosaurs, which comprised most of the species, died out 200 million years ago.

Unlike dinosaurs, ichthyosaurs barely left a trace of fossil remains, and “why that is remains a great mystery to this day,” said Mr Sander, lead author of the paper in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

The specimens in question were unearthed between 1976 and 1990 during geological surveys, but were only recently analysed in detail.

Ichthyosaurs were previously thought to have only inhabited the deep ocean, but the rocks from which the new fossils derive are believed to have been at the bottom of a shallow coastal area. It could be that some of the giants followed schools of fish there.

There are two sets of skeletal remains. One consists of ten rib fragments and a vertebra, suggesting an animal about 20m long, which is more or less equivalent to the largest ichthyosaur to have been found, in Canada.

The second animal measured 15m, according to an estimate from the seven vertebrae found.

“From our point of view, however, the tooth is particularly exciting,” explained Mr Sander.

“Because this is huge by ichthyosaur standards: Its root was 60 millimetres (2.5 inches) in diameter — the largest specimen still in a complete skull to date was 20 millimetres and came from an ichthyosaur that was nearly 18 metres long.”

While this could indicate a beast of epic proportions, it is more likely to have come from an ichthyosaur with particularly gigantic teeth, rather than a particularly gigantic ichthyosaur.

Current research holds that extreme gigantism is incompatible with a predatory lifestyle requiring teeth.

That is why the largest known animal to have ever lived — the blue whale at 30 metres long and 150 tons — lacks teeth.

Blue whales are filter feeders, while the much smaller sperm whales, at 20m long and 50 tonnes, are hunters, and use more of their energy to fuel their muscles.

“Marine predators therefore probably can't get much bigger than a sperm whale,” Mr Sander said, though more fossils would need to be found to know for certain. “Maybe there are more remains of the giant sea creatures hidden beneath the glaciers,” he said.

The paleontologist first held the fossilised bones in his hands three decades ago. At that time, he was still a doctoral student at the University of Zurich. In the meantime, the material had been somewhat forgotten. “Recently, though, more remains of giant ichthyosaurs have appeared,” the researcher said. “So it seemed worthwhile to us to analyse the Swiss finds again in more detail as well.”