PORT-AU-PRINCE // As rescue teams drove chaotically around Haiti's earthquake-ravaged capital scouring for survivors, Guensmork Alcin was quick to realise how technology could play a life-saving role after his Caribbean homeland's worst disaster in centuries.

Mr Alcin, who lived in Port-au-Prince's notorious slum, Cité Soleil, joined forces with others to chart the unmapped streets of his sprawling city to an open-access website and guide aid workers to the trapped and injured. As buried survivors desperately text-messaged their location to relatives and aid teams used online maps to orchestrate rescues, Haiti's earthquake of January 12 became a testing ground for how new technology can help in a crisis.

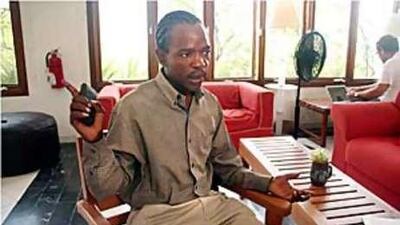

"It was hard for the emergency teams to know exactly where their help was needed, how to reach there and what condition the roads were in," Mr Alcin, 42, said. "The maps were bad. There were no addresses - that's why OpenStreetMap came to Haiti. Immediately I was interested as an agent for my community." The United Nations has labelled Mr Alcin a "hero of Haiti" for spearheading efforts to upload GPS co-ordinates of uncharted streets to the website and build a comprehensive map of Cité Soleil.

Mr Alcin said: "You take two points of reference: the beginning and end of a street. Make notes about the terrain, whether it is asphalted and what cars can traverse the road. Then I used my laptop to upload data to the OpenStreetMap server. The information went directly on the map for everyone to access." Leonard Doyle, a spokesman for the UN's migration agency, said online mapping became a vital resource for rescue teams that had been navigating with Lonely Planet travel guides and outdated charts that detailed less than a third of Port-au-Prince's streets.

As rescue efforts grew, citizens added details of field clinics, shelters and information about available bed spaces or whether doctors were treating infections, broken bones or carrying out life-saving surgery. Dreamed up by two Britons sitting in an English pub discussing the high costs of maps, OpenStreetMap, which launched in 2004, allows a growing community of users such as Mr Alcin to build an online chart using handheld GPS readers.

With about four fifths of Haitians carrying mobile phones, survivors trapped under rubble were able to exploit a telecommunications network that worked sporadically after the 7.0-magnituide earthquake of January 12 and text message their location to loved ones. Anxious relatives then forwarded messages to a 4636 number that was set up by another open-source website for helping during crises, called Ushahidi, which ran an emergency data centre from Tufts University in Massachusetts in the United States.

Ushahidi, the Swahili word for "testimony", was born in 2008 to allow Kenyans to report incidents of post-election violence via text message and e-mail and build online maps showing hotspots across the east African nation. Jaroslav Valuch, who co-ordinated the Haiti response, said Ushahidi received 10,000 alerts, many of which had to be translated from Creole by volunteer diaspora Haitians in the US, including 2,500 messages that provided details rescuers could use.

Although passing information to the US Coastguard helped save lives daily after the quake, Mr Valuch characterises Haiti as a testing ground for new technology but "not yet a revolution in the humanitarian system". "What I would say is that we introduced for the first time and implemented this concept of crowd sourcing crisis information from the affected population and we managed to link this information with the responders. So we introduced - and let's say tested - this new idea," he said.

"There are a lot of outcomes and lessons learnt that will help us - and not only us but the entire humanitarian community - to build upon this and start reviewing and planning ahead for the future, how these types of tools can be used in situations like this." Mr Doyle, from the International Organisation for Migration, said rescue teams cross-referenced alerts from the Ushahidi site with the emerging city plans being posted on OpenStreetMap to locate survivors, and worked out the best way to reach them.

Praising the "wisdom of crowds", he said open-source websites allow citizens to help in disasters and make their voices heard. Countering claims that they are easy prey for charlatans, he said web-users would correct fake data. "Just like in Wikipedia, the community is the police force." "Until you map your community you don't know where you're going," Mr Doyle said. "These sites can bring more efficiency to humanitarian work or give a voice to the voiceless, and let the little guy in the street know 'I exist, I am here, I have rights and I can communicate without any interference or censorship'."

Although open-source information was widely tested in Haiti, it already underwent trials reporting on electoral fraud in Mexico, Israel's invasion of Gaza and violence in Pakistan. Ushaidi currently hosts an "oil spills crisis map" for the Gulf of Mexico. The internet guru Clay Shirky has described a "cognitive surplus" in which the world's combined tech-users have more than one trillion free hours to contribute on shared projects each year, with sites such as Ushahidi and OpenStreetMap providing a forum. Back in Port-au-Prince, the tech-savvy Mr Alcin fears Haiti could again become a laboratory for crisis technologies. With 1.6 million vulnerable people still living in tent cities, rescuers will use web-based maps during a hurricane season expected to rank among the wettest on record.

"These are some of the best tools we can have to face another catastrophe like a hurricane," Mr Alcin said. "We didn't only just map the areas, we have information on hospitals, where they are, what kind of treatment they offer, where shelters are and how many people they can accommodate. It is one of the best tools an aid worker can have access to in an emergency." @Email:jreinl@thenational.ae * With additional reporting by Steven Stanek in Washington

Read our previous reports on Haiti six months after the earthquake here and here. Watch and hear our audio-visual report on Haiti six months after the earthquake here.