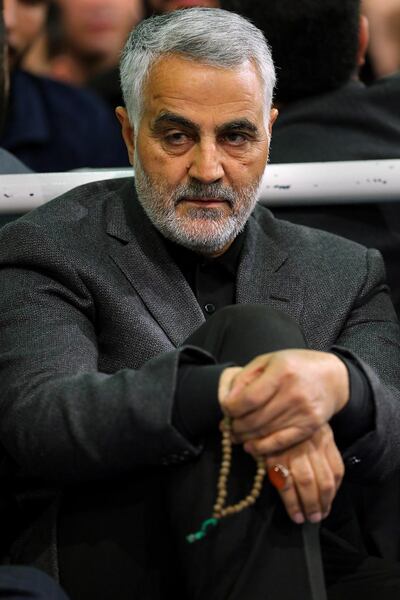

The killing of the powerful Iranian commander Qassem Suleimani in a US air strike at Baghdad airport ratchets up Iranian-American tensions to levels unseen in recent history.

Suleimani, 62, known to his supporters as “Hajji Qassem”, had just arrived from Lebanon, according to Iran's state news agency IRNA. Waiting for him at the airport were Kataib Hezbollah leader Abu Mahdi Al Muhandis and Mohamed Al Jaberi, another senior figure in Iraq's Iran-backed militias, who were also killed in the strike.

The operation was less about US intelligence learning of Suleimani's exact whereabouts and more about the decision to eliminate him. The leader of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard's Quds Force had been a frequent visitor to Baghdad ever since the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003. US authorities were aware of his visits, and at times exchanged messages through intermediaries, according to the New Yorker.

Suleimani's reach and influence in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon had grown significantly in the last 13 years. He was a quiet strategist next to Hezbollah's leader Hassan Nasrallah in Lebanon during the 2006 war against Israel, and a critical asset for the Bashar Al Assad regime who helped ensure its survival in Syria. In Iraq, Suleimani was both feared and admired. He secured Iran's influence over a vast network of Iraqi politicians and militias through cash payments, gifts and violence, according to documents obtained by the New York Times. Former US presidents George W Bush and Barack Obama recognised his anti-US agenda, but did not order his killing so as not to risk wider conflict with Iran.

That is what makes Friday’s attack different. A statement by the Pentagon confirmed that US President Donald Trump ordered the strike.

“At the direction of the President, the US military has taken decisive defensive action to protect US personnel abroad by killing Qassem Suleimani,” it said.

It accused Suleimani of “actively developing plans to attack American diplomats and service members in Iraq and throughout the region".

But with Suleimani gone, the US may have opened the door for limited direct confrontation with Iran. This is the highest-level assassination of an Iranian commander by the US since the 1979 revolution. It is a game changer in terms of battle tactics and the scope of tensions between the two countries.

While Israel has killed Iranian military officers and Hezbollah commander Imad Mughniyeh in Syria, Suleimani is in a different category. A pious, quiet thinker, he was able to weave the military structure of “the axis of resistance” from Iraq to Lebanon. He defied a travel ban and visited Moscow in 2015 to lead negotiations on Syria that secured a win for Mr Al Assad in Aleppo.

His killing robs his allies of a master military tactician, a thinker and an operator known for playing the long game, and an effective politician. Those are the same reasons why it will be met with heavy retribution.

A US defence source told The National that Washington has drawn up contingency plans if its assets or personnel are targeted. These involve possible US action inside Iran against its Revolutionary Guard.

But for Iran, a response seems inevitable. Tehran is already suspected of hitting tankers in the Gulf waters near Hormuz and firing missiles at two Saudi oil facilities in response to US sanctions pressure. Its military proxies are active in Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, Iraq, Gaza and Bahrain.

With more US sanctions expected on Iran, ongoing protests in Iraq and Lebanon threatening Tehran’s grip, and now the killing of Suleimani, Iran and Mr Trump may have reached the point of no return in their escalation spiral.