TUNIS // Five days after revolt against him broke out in February, Muammar Qaddafi mounted a podium in Tripoli vowing never to relinquish control of the country he had ruled for more than four decades.

"I am a glory that Libya cannot forego and the Libyan people cannot forego!" he shouted with characteristic bombast. "Muammar Qaddafi is history, resistance, liberty, glory, revolution!"

Eight months later, Qaddafi was dead, reportedly shot yesterday while trying to flee his besieged home town of Sirte; he was 69. At turns flamboyant and brutal, he leaves to Libyans a country scarred by his quest to remake it in his own image.

With Sirte's capture, Libya's National Transitional Council (NTC) is expected to declare the country liberated. It must now address the legacy of corruption, autocracy and violence that characterised Qaddafi's "Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya."

For centuries Libya was not a candidate for greatness. Called the "arid nurse of lions" by the Roman poet Horace, the country is mostly desert with its 6 million inhabitants clustered in a handful of cities.

Libya struck oil in 1959, attracting western oil firms, but King Idris invested little of Libya's new wealth in creating jobs. Meanwhile, Arab nationalist sentiment seeped in from the east.

It was this environment that helped shape a young Qaddafi.

Born according to most accounts in 1942 to a nomadic horse trader, Qaddafi grew up in the coastal city of Sirte. In the late 1950s he became politically conscious.

"Arab nationalism was exploding," Qaddafi told Time magazine in 1973. "The Suez Canal had been nationalised by the Egyptians in 1956; Algeria was fighting for its independence. The monarchy had been overthrown in Iraq. In Libya, nothing was happening."

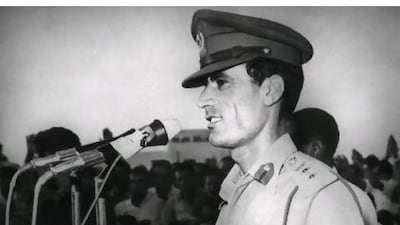

On the morning of September 1, 1969, army tanks converged on Tripoli, and King Idris's government swiftly collapsed.

The officers who staged the coup declared its aims as "unity, freedom and socialism", and warned that all resistance would be "crushed ruthlessly and decisively." At their head was 27 year-old Captain Muammar Qaddafi.

The Arab world hailed the coup as a rejoinder to Arab defeat in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. It was also a personal triumph for Qaddafi, who had seen himself as "a leader without a country".

In the late 1970s Libya was reorganised as a jamahiriya, a term minted by Qaddafi to mean "state of the masses". In reality, Libya remained firmly under his own control.

Industries were nationalised and political parties banned, while disastrous experiments with collectivisation during the 1980s gutted the economy and impoverished millions of ordinary Libyans.

Meanwhile, Qaddafi embarked on a whirlwind of quixotic projects, dragging Libya with him.

In the name of pan-Arabism, he forged abortive unions with Egypt, Syria and Tunisia. Evoking Africa solidarity, he lavished Libya's oil wealth on sub-Saharan countries.

Famously, Qaddafi bankrolled liberation movements and militants groups, from the Irish Republican Army to Liberian warlord Charles Taylor.

Libya attacked neighbouring Chad repeatedly during the late 1970s and 1980s.

For most of his career, Qaddafi's chief foe was the United States, which bombed one of his houses in Tripoli in 1986 following a bombing in Berlin that targeted US soldiers and was blamed on Libyan agents.

Two years later, four days before Christmas, Pan Am flight 103 from London exploded over the Scottish town of Lockerbie, killing 234 passengers, 16 crew and 11 people on the ground.

British and US authorities blamed the attack on Libyan agents, and the United Nations slapped international sanctions on Libya. In 1999, staggering under diplomatic and economic pressure, Libya began secret talks with the US and UK on repairing relations.

Two Lockerbie bombing suspects were surrendered for trial, and in 2003 Libya renounced attempts to acquire a nuclear weapon. By 2005 both US and UN sanctions were lifted against the country, and western oil firms were once again pumping Libyan oil.

That rapprochement came to a halt in February when Libyans inspired by revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt rose up against Qaddafi's regime.

In the eight months of war that followed, Qaddafi reminded Libyans - and the world - of his determination to keep power at virtually all costs.

Thousands have died and many thousands more are missing, according to the NTC authorities.

As cities have fallen to NTC forces, evidence has emerged of executions and mass killings apparently carried out by Qaddafi's regime, while Libyans have begun speaking openly of the torture and death visited for years upon his critics.

Libyans will remember Qaddafi the showman, a larger-than-life character who travelled abroad with a tent and female bodyguards, and in later years wore an endless series of African-themed ensembles.

But they will also remember Muammar Qaddafi the megalomaniac, who styled himself "the dean of Arab rulers, the king of kings of Africa and the imam of Muslims", and once likened himself to the Libyan-born Roman emperor Septimius Severus.

That comparison was perhaps more telling than Qaddafi intended. Like Libya's modern tyrant, Severus seized power via military coup and executed critics.

One mystery that Qaddafi leaves behind is how much he may have believed the personal myth he created.

According to Muhammad Al Hawni, a Libyan businessman and confidant of Qaddafi's son, Saif Al Islam, interviewed by Vanity Fair magazine for an article published in August, the elder Qaddafi may have lived to some extent in a world of his aspirations.

Advising Saif Al Islam last December on how to handle the threat of revolution in Libya, Mr Al Hawni said that he told the younger Qaddafi, "Do not create a shock. If you want progress and reform in Libya, don't contradict your father's virtual world."

Two months later, Muammar Qaddafi assured reporters for the BBC, ABC and London's Sunday Times that "they love me, all my people with me, they love me all. They will die to protect me, my people."

Even as Libya's new rulers vow to cleanse the country of Qaddafi's rule, this mark will remain indelible: some of his people did die to defend him, others died to bring him down, and many more died simply because of him.