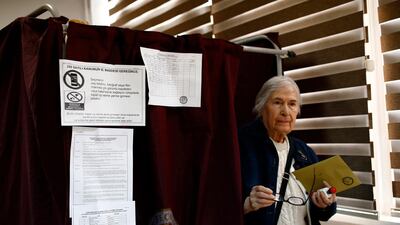

Millions of Turks started heading to the polls on Sunday for elections that have been billed as the most crucial in the country’s 95-year history.

Simultaneous presidential and parliamentary elections could see strongman Recep Tayyip Erdogan seal wide-ranging powers for himself under a reinforced presidency that would effectively end Turkey’s parliament-based system.

However, despite Mr Erdogan’s dominance on TV and in the press over the campaign, the race has proved to be the tightest he has faced since his Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in 2002.

After 66 days of mass rallies and election buses blaring party songs, Mr Erdogan leads all the opinion polls but an unusually well-organised and invigorated opposition has raised the distinct possibility that he will be forced into a run-off vote for the presidency.

The closeness of the vote – which could also see the AKP and its nationalist allies lose their majority in parliament – has rallied opposition supporters who see the poll as the last chance to save Turkish democracy amid a state of emergency introduced after an attempted coup two years ago.

Over the past 16 years, economic growth, Mr Erdogan’s sheer force of character and a deeply divided and ineffectual opposition has seen the AKP win all the elections it has contested.

______________

More on Turkey Election:

Turkey elections - live updates as Erdogan aims to retain presidency

Everything you need to know about the Turkish elections

Frenetic election campaign keeps pace in final day of Turkey election campaign

______________

However, there are signs that the economy is heading towards the kind of crisis that provided the backdrop to the AKP’s emergence. Inflation stands at 12.2 per cent; the current account deficit accounts for 6.5 per cent of GDP; unemployment is around 10 per cent; and the lira has lost about a fifth of its value this year.

It is the worsening economy that many say is the reason Mr Erdogan called elections 19 months early.

Coupled with this is Mr Erdogan’s own performance on the campaign trail. Once seen as a master orator, the 64-year-old appeared tongue-tied at a rally when his teleprompter apparently failed, and many of his speeches have provided the opposition with ample opportunity to ridicule him.

Perhaps the greatest miscalculation came before the elections were announced in April. A month earlier, AKP and Nationalist Action Party (MHP) pushed through a law to allow electoral alliances between parties. Seemingly designed to push the small MHP over the 10 per cent election threshold, the law also allowed opposition parties to come together.

Although widely regarded as unreliable, Turkish opinion polls suggest Mr Erdogan would fail to achieve more than 50 per cent of the vote, which is necessary to avoid a run-off on July 8 against the second-placed candidate.

Republican People’s Party (CHP) candidate Muharrem Ince, who is polling around 30 per cent, is likely to be the candidate who faces him but there are others in the four-party opposition alliance who could bite into Mr Erdogan’s share.

Meral Aksener, who heads the İYİ Party, appeals to conservative-nationalist voters while Temel Karamollaoglu, leader of the small Islamist Saadat Party, could also take some traditional AKP backers.

Outside of the two alliances stands the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), whose imprisoned former leader Selahattin Demirtas is standing in the presidential race.

Like Mrs Aksener, he is polling around 10 per cent, so seems unlikely to face Mr Erdogan in a potential second round. However, tactical voting could see the opposition, including HDP voters, throw its weight behind Mr Ince, a 54-year-old former physics teacher, as the anti-Erdogan candidate.

Tactical voting is also likely to weigh heavily on the parliamentary election.

Although a win for Mr Erdogan would see him surpass parliament’s powers, a hostile assembly could still serve as a brake on his desire for unimpeded executive authority.

For the opposition to dislodge the AKP-MHP majority in parliament, it is vital that the HDP passes the parliamentary threshold, as it did for the first time in June 2015.

If the HDP falls below the threshold, its votes will largely be redistributed to the AKP, the second-largest party in the Kurdish-majority south-east.

Another consideration is the possible effect of the parliamentary result on a presidential run-off. Should the opposition win parliament, it would dent Mr Erdogan’s reputation as an invincible vote-winner and give momentum to his opponents.

As the 56.3 million voters head to schools between 8am and 5pm to cast their ballots in 180,065 boxes across the country, the risk of electoral malpractice is at the front of many minds.

Last year’s referendum, which paved the way for Mr Erdogan’s presidential system when 51 per cent voted in favour, was marred by accusations of vote rigging that was not abated when the Supreme Electoral Council allowed the inclusion of unstamped ballots.

That ruling stands in today’s elections, as well as provisions that permit ballot boxes to be moved for security reasons and for the posting of law enforcement officials at polling stations.

The government has said these are to protect against voter intimidation in the south-east by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which has fought a three-decade insurgency against the state, but the opposition has called it an attempt to undermine the HDP vote.

Voters have to choose between six presidential candidates – Dogu Perincek of the leftist-nationalist Vatan Party is the sixth – and eight parliamentary parties.

Nearly 400 monitors from the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe will be deployed and more than half-a-million volunteers from opposition parties and civil society will use phone apps to record details of the count at their polling station.

The ballots of nearly 1.5 million expatriate Turks who voted abroad will be counted once the polls close in Turkey.

Should the vote result in an opposition-controlled parliament and Mr Erdogan in the presidential palace, Turkey can expect a period of instability and possibly further elections before the end of the year, as happened three years ago when the AKP regained its lost parliamentary majority three months after the June election returned a hung parliament.