NEW YORK // Abraham Kur Achiek describes being emotionally scarred after spending three years toting an assault rifle, witnessing atrocities and watching his comrades get shot and killed during his time as a child soldier in a Sudanese resistance army.

Now, as a 34-year-old officer for the UN's agency for children, Unicef, he struggles to put his past behind him and assist children who remain enlisted in the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) to ditch their Kalashnikovs and embrace civilian life. But despite a recent agreement by the SPLA to entirely abandon the use of child soldiers, experts fear the gains made in tackling the use of underage combatants in southern Sudan could be lost as violence once again threatens to engulf the region.

"I have suffered beyond description and it required great personal effort to come out of that and be able to talk today," said Mr Achiek. "These are situations that somebody cannot recover from. They are among the worst things that can happen to human beings. But life continues and you have to struggle and see things positively. If you give up, that's the end of life." Mr Achiek's story is not unlike those of many others from his hometown of Bor, which was dragged into Africa's longest-running civil war between the Muslim-dominated north and the Christian and animist south.

As the conflict spread, the SPLA evacuated Mr Achiek, aged 12, to a refugee camp in neighbouring Ethiopia for schooling before he was trained to use an AK47 among various assault rifles and weapons and returned to his war-torn region as a 16-year-old soldier. The teenager fought in a platoon of nine, under commanders who saw him and other young soldiers as "braver and more energetic than the adults". A Christian, he thanks God that he was never harmed in conflict but laments bearing gruesome witness to comrades' deaths.

He describes witnessing starving families and other atrocities during a brutal 22-year conflict that claimed the lives of two million people and saw four million more displaced before the signing of a fragile 2005 peace deal. Other "lost boys" to join the ranks of rebel forces tell harrowing tales of being brainwashed, beaten and starved by the SPLA as they underwent arduous training and learnt to kill enemies in close combat with machetes, guns and grenades.

Emmanuel Jal, the African rap star whose lyrics describe his time as an SPLA child soldier, tells of the sense of power children feel when clasping an AK47 and their desire to secure revenge for atrocities inflicted against their community by Muslim soldiers from the north. After three years of service, Mr Achiek fled his unit for a refugee camp of about 85,000 people in neighbouring Kenya, eventually gaining an education and working for the United Nations before heading back to Sudan in 2004. He has worked with Unicef demobilising and counselling former child soldiers in Wau for three years.

"You find many children that are involved in the war become traumatised," he said. "Some live with these memories and they keep them their whole lives. I started talking about what happened to me, but there are some other children that internalise what they saw. It is difficult for them to recover." Although he now has a wife and three children, Mr Achiek lost both his parents in the war and struggled to bring his brother and two sisters back together again after some degree of stability was returned to his turbulent nation.

The SPLA is understood to have reduced its contingent of child soldiers from an estimated 12,000 upon signing the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement to about 1,200 presently, and last month signed a renewed commitment to rid its ranks of all under-18s. Radhika Coomaraswamy, the UN chief's special representative for children and armed conflict, said the new deal has more powerful teeth than previous agreements because it allows the world body's staff to make surprise checks on SPLA barracks and training camps.

Compared to her previous fact-finding mission to Sudan in 2007, she said there is now "an acceptance of international standards across a large cross-section of people, both in government and outside, and a willingness to talk about these standards, especially on violence against women and children's rights". But Ms Coomaraswamy, and other experts on Sudan's travails, are concerned that child soldiers could be dragged back into the armed forces should the fragile peace between north and south shatter into renewed fighting.

Ms Coomaraswamy said the SPLA is complying with international rules while "peace prevails", but may return to recruiting and training children to swell its ranks if the southern community was once again fighting for survival. "I worry what would happen if war breaks out again between the north and the south, and all the gains could be lost," she said. @Email:jreinl@thenational.ae

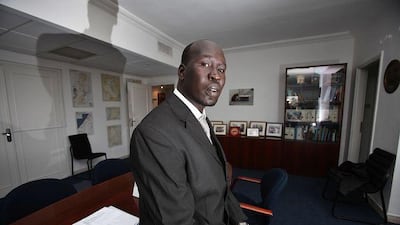

'I was a child soldier in Sudan - I suffered'

Abraham Kur Achiek survived years as a Sudanese teenage combatant. Today he worries that rising violence will increase demand for young troops.

Most popular today