For two years British sculptor Piers Secunda has painstakingly worked hard to restore and replicate many of the priceless treasures destroyed by ISIS.

Now an exhibition of his work, Owning the Past: from Mesopotamia to Iraq, has opened at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

ISIS looted and destroyed thousands of ancient artefacts in museums and at the Nirgal Gate, one of several entrances to Nineveh, the capital of the Assyrian empire.

One of worst hit areas, was Iraq’s second largest museum the Mosul Museum, which contained ancient Assyrian relics.

The 44-year-old sculptor spoke to The National about the "harrowing" scenes he witnessed when he was confronted with the devastation left behind.

“It was pretty horrendous for me going to the Mosul Museum, there were people who had worked there who had witnessed the arrival of ISIS, their stories were horrifying,” he said.

“It was difficult as an artist to see the damage ISIS had done and take moulds of the damaged sculptures but my job was to make sure we left with these moulds. It was harrowing for me to see what they had done there.

“At one site I had to walk away and compose myself.”

He was commissioned by the Ashmolean to carry out the work and went to Mosul in 2018.

Previously he has carried out similar projects around the world restoring the damage caused by terror groups.

It has taken over a year to restore and replicate more than 600 of the lost treasures in his London studio.

“It has taken years for me to be able to get to the ancient sites because I was unable to go beyond the frontline of ISIS,” he said.

“I think the most important thing is that the Ashmolean gave me the opportunity to make these works using moulds from the broken artefacts.

“There has been no project on this scale and it has been really important to me to expand on the message of the work about the fragility of these artefacts and the culture and value they hold and expose the damage that was done to them when ISIS began systematically targeting them and our history.

“I was worried the pieces would not achieve the emotional impact which I felt and I wanted other people to understand, but I felt a great sense of relief when I managed to do that.”

One of the pieces he worked on contained Sumerian cuneiform script, the world's oldest writing system.

Many of the relics dated from the Sumerian era, one of the first human civilisations whose people lived along the banks of the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers some 3,000 years ago.

Sculptures, pottery and cuneiform writing tablets dating from this civilisation were among the works destroyed by ISIS troops.

“Secunda’s work examines some of the most significant subjects of our time – including the deliberate destruction of culture,” a spokesperson for the Ashmolean Museum said.

“His powerful artwork was created by laser scanning and 3D printing a reproduction of the Assyrian relief of a bird-headed spirit that had been removed from the site of Nimrud in the mid-nineteenth century and is now in the Ashmolean.

“Secunda casts the pieces in the installation in industrial floor paint, with the broken stone texture transferred from moulds, which the artist made from the sculptures smashed by ISIS.

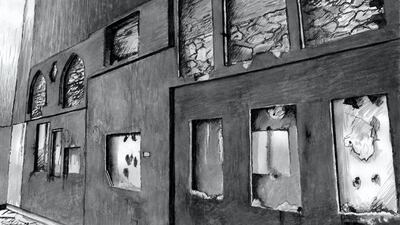

“He used charcoal gathered from the partly burned Mosul Museum to make ink by the traditional process of grinding the charcoal into a powder with a mortar and pestle, mixing it with alcohol and then Gum Arabic. He used this ink to make drawings of the interior of the Mosul Museum, based on photographs, bringing burned remnants of the artefacts and the building back to life as new works of art.”

The full exhibition critically examines the role Oxford University played during the early 20th century in the formation of the nation state of Iraq, previously Mesopotamia, and the importance of the remains of the ancient past in modern cultural identities.

Using a selection of objects, maps and diaries featured in the exhibition, residents from the Middle East reflect on the colonial legacy that continues to have an impact today.

The exhibition looks at the creation of Iraq’s geographic borders and the impact it had on its communities and was inspired by ISIS’ attempts to erase the borders and, with it, the identities of its people and their histories, the museum’s spokesperson said.

Dr Xa Sturgis, director of the Ashmolean Museum, said: “We are proud to present this exhibition which explores this particularly difficult period in Iraq and Oxford’s linked history.

“We are grateful to the local participants who dedicated their time and shared their thoughts and experiences, allowing us to present such an insightful and personal display. Through this and Secunda’s work, the exhibition shows the significant legacy of this pivotal time that still resonates more than a century on and across generations.”

The exhibition runs until May 2021.