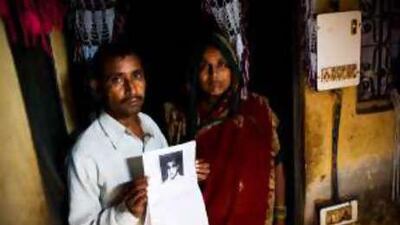

New Delhi // Pal Singh speaks quietly when he talks of his son Ashish. Almost a year and a half has passed since the boy disappeared and neither anger nor tears have brought any news of him. Like the other boys in the village of Prem Nagar on the outskirts of north-west Delhi, Ashish used to spend his free time practising cricket in the narrow alleyways that divide the low-slung houses, or playing on a patch of open ground not far from his house.

One morning in May last year, however, Ashish went out to play and never came home. He was 13. Mr Singh, 36, hired an auto-rickshaw and a megaphone and spent the day driving around the neighbourhood calling for information about his son, but no one had seen Ashish. He had simply vanished. "He must have been abducted. He is old enough to know where his house is. We only hope he survives," Mr Singh said.

Ashish is not the first boy to go missing from Prem Nagar, which is mainly populated by poor migrant workers - another child of the same age was injected with a sedative while standing in a sweets shop the year before and put to work in a small factory. He escaped by jumping off the roof. Stories like this are rife in poor communities across India. According to official statistics, 44,000 Indian children go missing every year - a figure that works out as one child every 12 minutes.

Only one-quarter of those children are found. But many activists say the true figure may be closer to a million because police are reluctant to register and investigate such cases and some parents even sell their children or hand them to touts offering work or education. The number may rise even higher, according to aid agencies, after massive floods hit the north-eastern state of Bihar last month displacing up to three million people and ruining crops for the coming year.

One of the poorest and most populous states in India, Bihar has long been a primary source of the country's trafficked women and children. "Bihar has always had a network of brokers and agents who are now exploiting the situation to their best advantage; they have been faster than the government in reaching these people," said Shanta Sinha, chairwoman of National Commission for the Protection of Child Rights.

Unicef, the United Nations children's agency, also predicts that this year's floods - the worst in 50 years - could make Bihar's young even more vulnerable to traffickers. "Just like after the [2004] tsunami, you have children who are separated from their families," said Victoria Rialp, head of child protection at Unicef India. "No one knows if they are really orphans or just separated from their parents."

One child rights organisation, Bachpan Bachao Aandolan, has rescued 20 children between the ages of eight and 13 from the clutches of traffickers at Bihar train stations in the past three weeks alone. But the group estimates that hundreds more have already been smuggled out of the affected area, bound for the cities of Delhi, Mumbai and Kolkata, and the northern states of Haryana and Punjab. From there, they are sold into a variety of illegal trades based on their age and sex, according to a recent report by India's National Human Rights Commission.

It said most missing children end up working as forced labour in illegal settings or sex slaves, and even "as child beggars in begging rackets, as victims of illegal adoptions or forced marriages, or perhaps worse than any of these, as victims of organ trade and even grotesque cannibalism." The commission started compiling its report after the dismembered bodies of 21 children, some as young as three, were found stuffed into plastic bags behind a house in Delhi's affluent satellite township of Noida in Dec 2006.

One of those arrested confessed to raping and murdering the children and consuming some of their flesh, according to police at the time. The crimes had taken place over a three-year period, during which the local police had ignored repeated reports from migrant workers of children going missing from the neighbouring village of Nithari. By contrast, when the three-year-old son of a wealthy IT executive was kidnapped from the same area, police scrambled into action and recovered the boy within five days.

The issue was highlighted again last month when it emerged that children from the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu had been abducted and sold to orphanages for as little as 500 rupees (Dh40) each. Gangs working in some of the state's poorest areas targeted "pretty" children under the age of three who would appeal to foreign adoptive families, according to India's Central Bureau of Investigation.

Malaysian Social Services, the adoption agency accused of acquiring the children, is thought to have sent 120 children overseas. The government responded to the recent scandals by establishing the National Commission for the Protection of Child Rights last year. But critics say what is needed is a single federal police body to oversee state-level investigations into missing children, and to compile and share intelligence.

"The Government of India does not fully comply with the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking," said a US state department report, published in July, that placed India alongside the Democratic Republic of Congo, Tajikistan and Albania among countries to watch for trafficking. Activists say one of the main problems in India is that poor parents such as Ashish's and those in Nithari are largely ignored by state police when their children go missing. In some cases, they are even beaten for trying to get the police to pursue their cases, according to Reena Banerjee, the head of Nav Shristi, an organisation that helps families from Delhi's slums whose children have disappeared.

Volunteers at Nav Shristi accompany parents to the police station and produce plastic-wrapped placards with the missing children's photos and personal details. "These are voiceless people," Ms Banerjee said of the 50 families on her books in Delhi - which accounts for more than 11,000 missing children annually. Since Ashish disappeared, Mr Singh estimates he has spent 42,000 rupees on his search, including printing flyers of his son and placing ads in the classified section of newspapers.

The amount was a fortune relative to his wages even when he was working as a supervisor in a textile factory earning 6,000 rupees a month, but six months after Ashish went missing, Mr Singh lost his job because he was devoting so much time to the search. He now earns 4,000 rupees a month as a freelance tailor. And yet, like many parents of missing children, his greatest expense is for the tantrics or psychics, who claim to know the whereabouts of his child.

Recently he paid one tantric 5,000 rupees. "They all say the same thing: 'Your child is still alive, but is in custody'," Mr Singh said. And so he keeps searching, while keeping a watchful eye over his four other children, ages nine to 18. Outside their home, the narrow street reverberates with the sound of children spraying each other from the communal water pump. But Mr Singh's children no longer join in.

"Nobody is happy," he said. "Nobody wants to be happy." hgardner@thenational.ae