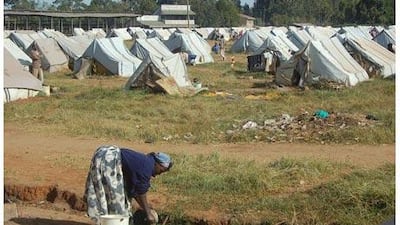

ELDORET, KENYA // It has been a year since the election that tore apart this normally stable east African country. The bloody tribal violence following the disputed poll that killed 1,200 and displaced 350,000 has long ended. Rival politicians are working side by side in a coalition government. One year after Kenya's worst crisis since independence, however, thousands of people are still living in squalid camps. Some of the displaced people say they prefer the safety of the camps to returning to live alongside the neighbours that destroyed their homes. Many still have no homes to return to and are waiting for government assistance. "We would like our elected officials to remember us voters," said Mercy Wangoi, the chairwoman of a camp in Eldoret in western Kenya. "We employed them and now they have forgotten us. We did nothing wrong except vote." The white plastic tent which has been Ms Wangoi's home for the past year has become frayed and torn from the weather. This camp at a fairground in Eldoret, which is still home to 2,500 displaced Kenyans, once held five times as many people. Many have gone home or have relocated to transit camps near their farms. But some, such as Ms Wangoi, who is a merchant from a nearby village, do not have the means to restart their lives. The government has promised 10,000 shillings (Dh477) to each displaced person to help them rebuild. Ms Wangoi, however, said she needed at least 10 times that amount to restart her business. "I lost everything," she said. "The 10,000 shillings, that is an insult." The problem started on Dec 27 2007, when Kenyans went to the polls to elect their president. Mwai Kibaki, the incumbent from the dominant Kikuyu tribe, was in a tight race with Raila Odinga, who is a Luo. As the early returns came in, Mr Odinga held a slight lead, but the count was creeping along at an agonising pace. Two days after the election, under pressure to announce a winner, the Kenya Election Commission declared that Mr Kibaki had been re-elected, although independent observers said the poll was flawed. Chaos ensued. Luos rioted in protest. In western Kenya, they hunted down their Kikuyu neighbours torching their homes and slaying them with machetes and bows and arrows. Kikuyus retaliated in some Rift Valley towns, killing Luos and members of other tribes. The bloodshed lasted for two months as the rival politicians continued to bicker over who really won the election. Finally, a mediation team led by Kofi Annan, the former UN secretary general, achieved a truce and the two sides worked out a power-sharing agreement with Mr Kibaki remaining president and Mr Odinga taking the newly created post of prime minister. The country has mostly returned to normal since the March deal. The electoral commission, which oversaw the flawed election, was disbanded. A commission of inquiry was established to investigate the causes of the violence. In its October report, the commission found that top politicians played a role in funding and inciting the violence. The coalition government has pledged to prosecute those politicians named in the report, although little progress has been made so far. Most of the displaced people were sent home in June and July, but about 60,000 are still without homes, according to the Kenyan Red Cross, which oversees the humanitarian effort. "One year later we still have people living in transit camps," said Patrick Nyongesa, the regional coordinator of the Kenyan Red Cross. "The issue is they need more support for reconstruction. We expected some areas to take longer, but one year is too long to get people resettled." The government, for its part, has built hundreds of homes and resettled almost 300,000 displaced people, said John Fedha, the deputy district commissioner in western Kenya. Though the government has given out millions of shillings to displaced people, he said some people still need more. "It is a token, but it is not a compensation," Mr Fedha said. "The government has a plan to assist all those people affected by the post-election violence by helping them restart their lives." Mr Fedha pointed out that the government has built 11 new police stations in his district to increase security. But some people are still afraid to return to their homes. "We are going nowhere. We have nowhere to go," Ms Wangoi said. "I can't go back and see my neighbour who took my things." Others, such as Simon Mwangi, have a more militant approach. He said clashes with his neighbours are inevitable when he returns to his village. "We know that if we go back we will start fighting," he said. "I will go back and take back the things that they stole. We are not going to tolerate it anymore. It is better to go back and die claiming my things than to stay here and die poor in this tent." mbrown@thenational.ae

Victims of Kenyan poll riots still seek peace

Politicians have long since made up but people affected by bloody riots following disputed elections a year ago fear returning home.

Most popular today