In South Africa's remote Karoo steppe, the town of Orania is little more than a ramble of lanes and a few modest bungalows. Street names are stencilled onto the kerbstones. Sheep graze nearby. Concrete road slabs give way to pebbles, dirt and potholes. What passes for the town centre has just a small bakery, a church, a grocery store and the offices of the local authorities. Nearby, one of the town's two bars occupies a wooden shell on the edge of what looks like a scrapyard for disused agricultural vehicles.

It was here in Orania, on a Saturday afternoon in the middle of last month, that the body of Dr Carel Boshoff was lowered into the arid soil. Twenty years before he had established the town as an all-white enclave. Now, the founder may be dead, but his life's work, to establish an independent Afrikaner homeland, stubbornly refuses to follow suit.

"There's been an estrangement between Afrikaners and South Africa, which is becoming a dysfunctional state," Boshoff's son and heir Carel Boshoff IV tells me. With the help of 900 or so true believers, Carel Jr keeps the autonomous Afrikaner community alive. "We are still viewed as the previous elite: the perpetrators, a previously dominant and very visible minority", he says. "So where do you go when you are less than a 10 per cent minority in a system dominated by others?"

Like his late father, a theologist, Orania's current leader is no populist demagogue. The bespectacled former philosophy lecturer looks like a mix between Woody Allen and Boris Becker and peppers his speech with words like "ontological" and "relativised". Boshoff openly concedes that the utopian farming project has not lured anywhere near the expected number of settlers.

"We have seen that we don't attract the masses," he admits. "There are more Afrikaners living in London than in Orania." Nevertheless, he believes the tide may yet turn in the town's favour. "Orania offers the symbolic embodiment of a re-established Afrikaner collectivity that can once again become a historical agent," he says.

There are two main narratives about this small, privately owned agricultural community. One, common among white liberals, paints Orania as a bombastic and pathetic outpost of embittered racists who refuse to live side by side with their newly equal black countrymen. The other, prevalent among many blacks, sees a privatised gated community shielded by a 1950s-style fantasy from crime, poverty, political turmoil and declining white privilege.

Yet the putative Afrikaner homeland is hardly an oasis of privilege. Though it has a flag and even its own currency (the Ora), Orania lacks most of the traditional accoutrements of white South African living: no private swimming pools or landscaped gardens, glass-walled conservatories and two car garages; no luxury high-rises or mansions with their granny flats and quarters for servants (now euphemistically called "domestic workers"). Clearly, those who retreated to this kibbutz-like settlement were not doing so to preserve their elite status or material luxuries. Why did they come?

***

"I don't like black people, I'm sorry," says Barbara, a handsome, ashen-faced woman who I meet as she sits outside the town bakery. That isn't the reason she gives for moving here from KwaZulu Natal a year ago, however. Orania, she says, is the only place where her husband, a lorry driver, could find a job thanks to affirmative action policies that favour blacks. Here, all jobs, from the white-collar to the janitorial, are reserved exclusively for white Afrikaners. Many residents have similar stories. Poverty among blue-collar whites has surged. A recent Standard Bank of South Africa study found the number of whites earning less than $80 a month grew by more than 50 per cent from 2000 to 2004. Apartheid's passing marked the end of artificially protected jobs for low-skilled, poorly educated whites, disproportionate numbers of whom were Afrikaners. In a country with an unemployment rate of 24 per cent, they now compete with similarly low-skilled blacks, who are more numerous, willing to work for lower wages, and who benefit from affirmative action policies that take into account race but not class or wealth.

Other arrivals to Orania are victims of crime. Nearly everyone in the town has a story to tell about having been or knowing someone who has been robbed, stabbed or killed. Violence actually affects blacks more frequently than whites, but for many Afrikaners, the most important feature of the new regime is that they are no longer safe.

"We are living in Orania to protect our language and our culture, not because we hate other people," says Nikke Strydom, a 21-year-old politics student attending nearby Pretoria University who moved here with her parents as an adolescent. Nikke straddles two conflicting Afrikaner identities: at once a modern, upwardly mobile young woman at a prestigious, urban, racially diverse university, and an Afrikaner traditionalist deeply committed to a project of rural self-reliance and racial separation.

"People think we are here because we hate the blacks or whatever, which isn't true at all," she says. "But because of the history and the whole apartheid thing, people don't see it like that."

"We're not here to be a white community - we're here to be an Afrikaner community", concurs Jaco Kleynhans, the movement's PR director.

Yet what makes Orania different from other Afrikaner communities in the suburbs of Cape Town and Johannesburg is the absence of any black people at all, except for occasional visitors to the OK Supermarket from surrounding villages. There are no black shop clerks, engineers, gardeners, maids, civil servants, petrol station attendants, teachers, waiters, nurses or labourers. A teenager recounted how he had been playing the online video game Starcraft with someone in Russia. "In the middle of the game, he had to pause to go help his dad dig the car out of the snow! Can you believe it?", he asked excitedly: a white South African more likely to communicate with a person living thousands of kilometres away than with a black countryman from the next town.

"They are just afraid of black people here", pronounces a plain-spoken Johannesburg building inspector holidaying in Orania, where his mother-in-law now lives. He says he doesn't understand the place: "It's such a waste to do everything here with white labour," he told me. "Sure, black labour can steal, murder and rape. But it is cheap."

Locals, however, say they actually have more respect for black people than their assimilated white counterparts in the cosmopolitan cities.

"I think the problem in the cities is: OK you are the black guy, and you have to scrub my floors and do the dishes and so on, so why would I respect you?" asks Nikke. "I don't see black people as lower than me so they don't have to do my dirty work. I'll do it myself."

There's some truth in Nikke's argument. Still highly segregated and heavily reliant on domestic help, many South African suburbs look more like apartheid-era time-warps than Orania does.

"Why have someone else clean the toilet for you when you can do it yourself?" asks Karen, a young woman who works in the town cafe.

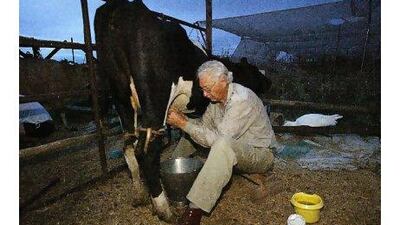

This spirit of Afrikaner self-reliance has a long history, from the time of their original settlement in the Cape to the Great Trek, when scores of farmers journeyed east by covered wagon to escape the colonial rule of the Dutch administration. It also animates Orania's present refusal to take any government grants or assistance, despite paying taxes. Yet there is another, calculatedly political rationale behind this fastidiousness in owing nothing to outsiders or the government.

"If you do your own work and you don't get foreign people to do it for you, then you have more say about what is happening," reasons Nikke, using the word "foreign" to describe black South Africans. "Because it's difficult to say: 'OK you can come and do my work but you can't have a say in the government'. So I think the whole idea behind Orania is to work yourself free."

Free of black political control, that is. If you let them work, you must also be prepared to let them have political control. But if you don't, then you can seclude yourself without guilt. From each according to ability, to each according to his work: it's an almost Marxist position for a group of conservative nationalists to take, but has an elegant consistency.

Like communist true believers criticising the Soviet Union for a lack of ideological purity, some Oranians feel that the apartheid ideal was betrayed by the old South Africa: that it wasn't "apart" enough. The mistake, they believe, wasn't the segregation itself but the exploitation, which predictably led to blacks demanding their rightful share. In Orania, they see the chance to rescue apartheid from its history, strip it of the implications of violent domination and minority rule, and repackage it to mean just what it says: living separately.

***

"I think apartheid was a good idea but they did it wrong", says Nikke. "I think it's not right to say, 'OK, you cannot come here', but each culture must have a place to be where they want to be. I don't think apartheid was as bad as they say, as they want to make it."

Orania offers such traditionally minded Afrikaners a third way between emigration and assimilation; a place to develop a secure identity as a national minority and not feel threatened. "Orania is the only place we can have a normal life, in the sense of it being peaceful, being among people like you, who speak your language", says Sebastiaan Biehl, a gaunt, khaki-clad amateur historian who has recently moved to the community. "Once you have your own land where you can be assured of your future, you can be good neighbours."

He and others deny walling themselves off. "The idea is to be a unique part of South Africa," says his friend Albert van Zyl, a university lecturer who is planning to settle here with his family.

"We want to contribute to the development of the country," claims Jaco Mulder, the provincial leader of the nationalist Freedom Front Plus party and owner of the cafe where Karen works, "because the lights must keep burning in all of South Africa in order for Orania to succeed."

Mulder says the town's pioneering eco-friendly irrigation network, strict recycling programme and mandatory solar-powered water heaters set a good example to nearby communities about bottom-up development, sustainable agriculture and efficient service delivery. Even the fiercely populist president Jacob Zuma visited and declared: "They want to co-operate with other communities so that everyone can learn together. Orania is part of us, and we are part of them." Last year, he appointed the leader of the Freedom Front party a deputy minister of forestries, fisheries and agriculture, a particularly important portfolio for Afrikaners, many of whom are farmers.

"Zuma understands us," says Sebastiaan. "Although he travels internationally, on the holidays he goes back to his roots in rural KwaZulu-Natal, to live like a Zulu and enjoy himself. There's no problem for him to understand that Afrikaners also need to be able to come here and relate to their roots."

Yet many black people continue to treat Orania with a mixture of bewilderment and suspicion. On my drive over, I had asked a petrol station attendant in a nearby town if she had heard of Orania. "Yes," she replied. "It is beautiful, but they don't like black people there. It's a strange place." Then she added: "I do my shopping at the OK Supermarket there sometimes."

"They cannot live with the fact that the world is changing and you have to get integrated or you'll lose out," says Tebzah Mbhele, a postgraduate student of urban planning at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. He thinks there's nothing wrong with protecting one's culture, but asks: "What are they scared of? Who are they protecting themselves against? They are holding on to the past like to an old piece of meat, but it is rotten."

Nevertheless, Albert van Zyl's brother Gerhard insists that blacks have an easier time comprehending Orania than whites. "My colleague at the iron ore mine where I work is a Tswana," he says. "And it is easier for me to explain Orania to him than to a lot of white people. White people think it's a racist thing, but as a Tswana, he knows that Afrikaners also need a place of their own. When I tell him that I plan on going to Orania for the weekend, he wishes me luck and doesn't have any bad feelings about it."

***

A major obstacle to such professed interracial understanding is Orania's quasi-religious relationship with Herdrik Verwoerd, the former prime minister known as the architect of apartheid (he also happens to be Boshoff's grandfather).

In the centre of town stands the shrine-like house where his widow lived out her last years. Attached to it is a museum housing Verwoerd's relics: the suit that he wore on the day he was assassinated by a mentally ill parliamentary staffer, the bloodied shirt punctured by five knife wounds marked with little cardboard labels; even his socks, wallet, and scuffed leather briefcase are preserved for posterity.

On a little hillside overlooking the town stands a semi circle of weathered bronze busts depicting Afrikaner political leaders, salvaged from demolition after 1994 and installed here.

Carel Boshoff says Verwoerd's centrality to Orania is the result of a simple family matter: the settlement was founded by Verwoerd's son-in-law. But residents' fondness for South Africa's first republican prime minister manifests a larger nostalgia for the old days.

"We built up this country," laments Sebastiaan, "and now it feels like we have to start all over again." Compounding the sense of loss is the perception, among many Afrikaners, that their language, culture and way of life are under threat from affirmative action, the spread of English, and a racial quota system called Black Economic Empowerment.

At a restaurant in the town's main hotel, I meet Ernst Roets, the youth leader of Afriforum, a conservative organisation campaigning for the cultural and economic rights of Afrikaners. He is on-message, smart and forceful. And savvy: his Facebook profile picture shows him sitting next to a black delegate at a political conference. Like all the young people I spoke to, Ernst calls affirmative action "reverse discrimination".

"It's time to move on", he says. "Our generation had nothing to do with apartheid; we did all our schooling under democracy, where blacks and whites had the same opportunities. Why should a black student who went to a private school and drives a BMW have an unfair advantage over a poor white student who went to a state school?" he asks.

"We were hardly born during apartheid, we didn't take part in it in any way, and still they hate us," says Nikke.

Oranians want to reposition the Afrikaner "brand" from its ignominious legacy into an ethnic minority like any other, deserving of cultural protections and group rights. Yet while the racial gap has shrunk since 1994, whites still earn nearly eight times more than blacks, according to the South African Institute of Race Relations.

Boshoff faults Afriforum for not adequately acknowledging the historic injustice ("It's senseless to say that my kids are not privileged by the privileges I had, and my father had," he admits). But he says that Afrikaners have become fed up with apologising for apartheid. "There's a broad sentiment that we've admitted enough guilt," he says. "There's even a popular song that goes 'we will not say sorry anymore'."

Settling in Orania, with its ascetic lifestyle and rustic self-sufficiency, is itself the best form of atonement, he claims.

"My father used to say, 'I've heard many people apologise for apartheid, but I haven't seen a single one of them sell their Mercedes and buy a bicycle instead'," Boshoff says.

"In Orania, we are not saying sorry with our mouths: we are doing something about it."

Vadim Nikitin is a freelance journalist. He blogs at foreignpolicyblogs.com