A team of French archaeologists last month unearthed a long-buried Assyrian winged bull, otherwise known as a lamassu, in Mosul, north Iraq, that dates back to the reign of King Sargon II from 722-705BC.

The priceless carving now exposed to the atmosphere and at risk of erosion won’t have to contend with the weather for too long because the Louvre has promptly, much to the chagrin of many Iraqis, vacated a spot to accommodate the piece.

As an Assyrian, the relationship I have with my ancient heritage can be conflicting. Growing up in the UK, the British Museum is like a second home. I have lost count of the number of times I’ve traipsed down the Assyrian galleries, with their depictions of war, lion hunts and eagle-headed winged genies. The contents are as close as I can physically get to my homeland.

Each visit would fill me with a combination of awe, and amusement at the uncanny similarity of the alabaster faces to that of my grandad's. Underlying these emotions is the sorrow of how they got there in the first place. Many miles from where they were found, ancient Assyrian heritage mirrors the modern Assyrian diaspora, scattered predominantly in the western world, and severed from their native land.

The official line is that the British Museum obtained its collection legitimately. Austen Henry Layard, a diplomat, was the first to excavate Nineveh and Nimrud in what was Mesopotamia in the mid-19th century. He swiftly received sponsorship and then embarked on a mammoth journey by ship, transporting the huge carved stone reliefs to England. Layard’s visit inspired other Europeans to follow and swell their public – as well as private – collections of treasures.

The region, under Ottoman rule, granted permission for removal of the antiquities although there is scant information about the nature of the transactions, and it appears highly improbable that locals were consulted in the process.

While I ultimately believe that these items belong in the land where they originated, I have several reservations about repatriation. Circumstances over the past few decades have made it challenging for Iraq to manage its antiquities. My mother recalls a trip to the aqueduct of Sennacherib in Jerwan in the late 1960s. The site, dating back to the seventh-century BC, was crawling with security guards, one of whom scolded her for attempting to reach out to touch a pebble.

Now it is unattended, which is sadly an all-too-common observation at similar archaeological sites. Last year, Chatham House published research detailing the extent to which Iraqi institutions lacked the funding to deliver the security and conservation gravely needed for these areas.

The recently found winged-bull sculpture in Mosul is, in fact, incomplete. The head was stolen during a previous excavation that was abandoned at the start of the Gulf War. The conflict and subsequent sanctions shattered the country economically and prompted an illegal trade in the trafficking of ancient goods.

This continued during the 2003 invasion when occupying troops setting up bases at historically significant grounds inflicted considerable damage, and peaked with the horrendous looting of the museum in Baghdad. Some of the artefacts found their way on to eBay; an example that stood out was an invaluable cuneiform slab being sold for $10 as a “coaster”.

It is thought that, in all, Iraq has lost hundreds of thousands of cultural objects. While some have been recovered, the occasional glimpse of others in private collections has sparked controversy. Perhaps most notable was a 3,000-year-old panel of gypsum depicting a deity called Apkallu sold at auction by Christie's New York in 2018. It had been acquired by an American Episcopal seminary in 1859 through Dr Henri Byron Haskell, a US missionary who was intrigued by artefacts with biblical relevance.

The auction provoked restitution claims from the Iraqi ministry of culture, with officials petitioning Unesco and Interpol to intervene, but to no avail. Christie's addressed Iraq's position, putting out proof of provenance of the item. It added it had contacted law enforcement authorities before publishing details of the sale to ensure the documentation for the alabaster relief met “applicable laws governing its sale”.

That piece went under the hammer to an anonymous buyer for $31 million – three times the estimated value – arguably because of ISIS taking a pneumatic drill to monuments of a similar era at the palace of Ashurnasirpal II in Nimrud a few years earlier.

What ISIS did not destroy they traded on the black market, generating millions of dollars. Little coverage was given to the fact that, at the same time the statues were being demolished, the descendants of those who built them were being systematically massacred by the very same terrorist organisation.

That disconnect between modern and ancient Assyrians within the narrative about Iraq is not coincidental. At no stage in Iraq’s history has the constitution acknowledged us as an ethnic group, still less our indigeneity. Our direct lineage to ancient Assyrians, despite linguistic, cultural, geographic and genetic evidence, is often questioned.

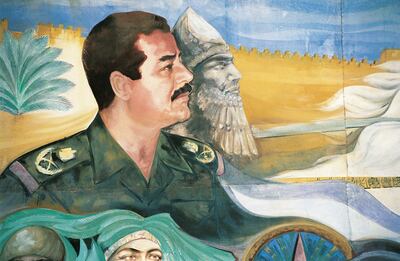

The Arab nationalist policies of Baathism reclassified Assyrians as “Arab Christians”, but that didn’t stop Saddam Hussein fashioning himself as king Nebuchadnezzar in murals across the country nor his somewhat problematic restoration of Babylon, where he ensured his name was inscribed on every brick.

In May, Iraq's president requested the return of approximately 6,000 artefacts that were “borrowed” in 1923 for “academic purposes”. Given the British Museum’s track record of declining previous calls to repatriate items, it is interesting that this request was granted unchallenged.

In Baghdad, a lavish ceremony took place to mark the occasion with President Abdul Latif Rashid at the helm, a man who has been an instrumental member of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan party. The party’s core ideology is establishing a state with a singular Kurdish identity.

With that in mind, seeing a politician salivate over our cultural heritage, proclaiming the goods as symbolic of national unity, was stomach turning. More so if you are aware of the role the party has had in marginalising Assyrian communities.

Dig a few inches down in Iraq and you will more than likely stumble upon something a few thousand years old. That’s exactly what happened to journalist Hormuz Mushi in the town of Fayda in 2019. After alerting the relevant authorities of his accidental find, Mushi was assaulted and detained by Kurdish security forces.

The bizarre response makes sense when understanding the objectives of the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) which presides over that part of Iraq. Such discoveries are viewed as a threat to the pursuit for Kurdish independence that has partially relied on discrediting Assyrian indigeneity.

The KRG are famed for co-option of Assyrian material heritage, adopting historical revisionism as a key tactic. A report by the Assyrian Policy Institute described disturbing examples, such as incorrect labelling of museum exhibits, frequent vandalisation of archaeological sites as well as tangible heritage being torn down altogether – or, as was the case with the Khinnis rock reliefs, being renovated into an outdoor swimming pool.

I can’t help but feel that Assyrian history is the one aspect of Mesopotamia’s back story that appears to belong to everyone but Assyrians. I laughed when my grandad first snorted “I could do with my portrait back” before a trip I made to the British Museum as a child. Now, as I remember those words, there is a poignancy to them that emphasises the lack of ownership we possess over our own past.

Michael Rakowitz, an American artist, wrote a letter to the British Museum in January requesting repatriation of a lamassu to Iraq. In exchange, he offered the Tate a contemporary version of the sculpture he had created.

To many Assyrians, this seemed like nothing more than a gimmick. If he succeeded, he would have achieved what no one else had done before, as well as immortalise himself with an artwork in a world-renowned gallery.

The recent thefts at the British Museum have been an unexpected twist in the timeline of the institution. In August, the museum reported that a number of items, including gold jewellery and precious stones, appeared to be missing or damaged. The incident, under investigation by police, led to the museum director Hartwig Fischer resigning. It emerged that concerns about possible thefts first raised by an art historian more than two years ago had gone unheeded. It has been suggested that inadequate cataloguing and lapses in security may have contributed to the losses. Fischer quit after accepting responsibility for the museum's failure to properly respond to warnings about the suspected thefts of thousands of objects as far back as 2021.

Until this point, I had always maintained that Assyrian artefacts were best placed where they are, in the British Museum. Iraqi authorities, on the other hand, have repeatedly failed to guard our physical heritage and are yet to realise the need to protect our modern communities, the numbers of which are continually dwindling. Until they can prove otherwise, I can’t help but feel that these relics are far safer underground.

Jenan Younis is a comedian and BBC New Voices Winner based in London. Her next show IRAQNOPHOBIA is at the Harrison Theatre, Bloomsbury, on Saturday, December 16.