For some, Iraq’s occupation of Kuwait never came to an end.

While many Kuwaitis are this week marking the 30th anniversary of the Gulf state’s liberation from Iraqi forces, for others it is an unhappy reminder of a loved one who has been missing for decades.

Sahar Tawfeeq, a spokeswoman for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which reunites families torn apart by conflict, says missing relatives are an enduring legacy of the First Gulf War in the early 1990s.

"You might think that after 30 years of waiting, families forget about the tragedy and get on with their lives," Ms Tawfeeq told The National.

“But these families are still waiting, even when there is very little hope of ever finding their loved ones.”

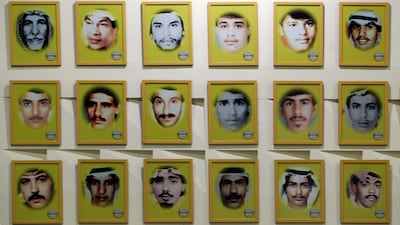

Kuwait says around 605 people, mostly Kuwaiti, disappeared during the conflict, when dictator Saddam Hussein sent troops into the Gulf nation.

Iraqi forces were forced out in February 1991 by a US-led coalition.

Most of those abducted were sent to jails in Iraq for refusing to co-operate with occupying forces. Testimony from Saddam-era officials suggests many were taken to underground prisons in Baghdad.

The abductees, mostly civilians, were never heard from again.

Researchers say they included 120 students, 50 teenagers and at least three nurses. The latter were detained for having treated wounded Kuwaitis.

Saddam denied all knowledge of the disappeared and frustrated attempts to find them after Kuwait was liberated.

After he was toppled from power in the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, co-operation between Kuwait, a new government in Baghdad and the ICRC led to the remains of 236 Kuwaitis and other nationals being identified in 2004.

But then followed a 16-year gap of little progress.

Frustration grew in Kuwait City as the search for the remaining 369 missing people ground to a halt.

ICRC visits to Iraq failed to discover victims’ whereabouts and years of political turmoil inside successive administrations in Iraq were also blamed for a lack of progress.

Instead, rumours spread of secret excavations, raising hopes of new finds.

“Our office in Basra is full of visitors whenever a rumour circulates about the discovery of human remains,” said Ms Tawfeeq.

“It’s a real problem in this age of social media. People share rumours and publish the names of people they say have been discovered. But sadly it’s often just fake news and people being manipulated.”

For this reason, the ICRC makes contact with families before announcing a discovery, said another spokesperson, Ala’a Nayel.

“Such uncertainty has severe psychological and emotional effects. Ricocheting between hope and despair, families mark anniversaries – one year, two years, and even decades,” said Ms Nayel.

“The trauma of ambiguous loss is one of the deepest wounds of war. The pain infects whole communities, lasting decades, preventing societies from reconciling.”

After years of stalled progress, 20 sets of human remains were in March 2019 exhumed from a gravesite in Samawah, about 270 kilometres south-east of Baghdad, and later transferred to Kuwait.

Kuwaiti officials said in January that DNA tests had identified them as among those missing since the 1991 invasion. The relatives were informed.

Ms Nayel said these "accomplishments provide tremendous hope for families who have waited decades for answers.

“After 30 years of painful waiting, the relatives of these missing persons were able to clarify the fate of their loved ones,” said Ms Nayel.

UN envoy Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert hailed “significant progress 16 years after the last identification”, at a UN Security Council meeting in January.

Iraqi-Kuwaiti cooperation was “clearly bearing fruit”, she added.

Hopes are high for more progress.

Excavators have uncovered more remains from gravesites in Samawah that are being studied. The “fragmented state” of bodies meant the “identification process had taken longer than initially expected”, says a UN report.

Officials plan to excavate burial sites at Samawah, Khamisiyah, Karbala and Salman Pak in Iraq, once Covid-19 restrictions are eased.

There are plans for “ground-penetrating radar” to scour for bones, the UN says.

Investigators searched for human remains at a suspected grave in Kuwait in March 2020 but "none were found", said Ms Nayel.

Ms Hennis-Plasschaert urged “all partners to seize the momentum of recent progress and to further advance the search”.

For bereaved Kuwaitis, attending a ceremony to hand over remains or visiting gravesites offers “closure”, said Ms Tawfeeq.

With some 350 files still open on Kuwait’s disappeared, the ICRC will not stop its work.

Still, the Iraq-based team has a mountain to climb.

“Iraq is one of ICRC's biggest missing person caseloads with hundreds of thousands of people gone missing over the decades, from the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s to Kuwait, the 2003 US invasion, the Islamic State group era and other situations,” said Ms Tawfeeq.

“We’re trying our best, it is not an easy task.”