In the introduction to its autumn blockbuster I Am Ashurbanipal, the British Museum claims that the man who ruled the ancient kingdom of Assyria in sixth century BC "wasn't modest … he called himself 'king of the world'!".

This, says the museum, was "quite a claim, but given the size of the empire, it wasn't far from the truth". The British Museum's often-repeated conceit, that it is "the museum of the world, for the world", is also quite a claim. Given the size of its collection, which numbers more than eight million objects, of which only one per cent are on show at any time, this isn't far from the truth.

What the institution – which must be praised for opening The Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World recently – means by being the "museum of the world" differs widely from the interpretation of that slogan by many countries whose treasures remain locked within its walls. There is, insists the famed museum: "A great public benefit to objects from across the world being accessible to millions of people here at the museum", but of course that advantage is limited to those who can travel to London. How many Iraqis will be able to make the journey to the British Museum to view the objects taken from their soil at the height of European imperialism?

This is an increasingly pressing question, one that was highlighted by the sale at Christie's this week of a 3,000-year-old frieze taken from an ancient palace in Nimrud, excavated in the 19th century. The carving of the "winged genius" was billed as the most exquisite piece of Assyrian art to reach the market in decades and formed the centrepiece of Christie's antiquities sale with an estimate of $10-15m.

The Iraqi government is demanding the return of the artefact that sold for almost $31 million (Dh114 billion).

Precedents are being set for the repatriation of such antiquities. In 2009, the Louvre returned fragments of wall paintings taken in the 1980s to Egypt, and this past March, French president Emmanuel Macron vowed to return artefacts looted from Africa during the colonial era. African heritage, he said, "cannot be a prisoner of European museums". In April, the V&A in London said it planned to return the on permanent loan items looted from Ethiopia by British troops 150 years ago, and in May, a Berlin museum returned items excavated in the 19th century from the ancestral graves of an Alaskan tribe.

The growing impression is of an imperial structure, long-overdue for demolition, finally beginning to crumble. The British Museum, however, has remained trenchantly opposed to such gestures. Its attitude is framed by its position over what the museum calls the Parthenon Sculptures, better known as the Elgin Marbles on account of their having been looted from Greece in the early 19th century by Lord Elgin, the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire.

Successive Greek governments have sought the return of the marbles, to complete the country’s collection, now on show in the Parthenon Gallery at the Acropolis Museum in Athens. The British Museum’s arguments for hanging on to the marbles are no stronger than its case for retaining any of the other objects in its collection taken under similar circumstances.

“Archaeologists worldwide,” says the museum, “are agreed that the surviving sculptures could never be re-attached to the structure”, but that is a response to a false premise – that’s not what the Greeks want to do. Lord Elgin, insists the museum was “acting with the full knowledge and permission of the Ottoman authorities”, but not of the Greeks, who weren’t exactly willing subjects of the Ottoman Empire. Furthermore, the sculptures, which are “part of everyone’s shared heritage and transcend cultural boundaries”, have always been on display to the public in the British Museum, “free of charge”.

Generous. But hardly a reason not to give them back. The British Museum argues it is a “unique resource for the world” that “tells the story of cultural achievement … from the dawn of human history over two million years ago”.

“The breadth and depth of its collection allows the world’s public to re-examine cultural identities and explore the connections between them.” Setting aside, there is the thorny issue of how it was acquired.

The role museums play today, argues the establishment, “is more important now than ever. Encyclopedic museums across the world can show visitors the interconnectivity of cultures, they can highlight our shared humanity as well as being a safe place to debate and think about contemporary questions within a historical context.” All true. But, given the small numbers of people who can actually afford to come to London, or any other western capital, to ponder the “shared” stories told by such “encyclopedic museums”, wouldn’t it be better to send the treasures back to where they originated, and shift the burden of paying to see them to the wealthy citizens of the West, whose forebears pinched them in the first place?

About half of the British Museum's collection can be viewed on its online database, which includes details of how objects were found, or acquired, and how they made their way to London. As such, it is a shameful record of imperial acquisition by this or that 19th or 20th-century adventurer/collector/diplomat/amateur archaeologist.

Examination of the collection reveals that perhaps no other recent exhibition at the British Museum makes the case for returning the looted treasures of the world to their homelands as persuasively as I Am Ashurbanipal, which opens on Thursday and runs until February 24.

Its collection contains tens of thousands of objects dug up at the sites of ancient Nimrud and Nineveh in the 19th century under the auspices of Austen Henry Layard, the archetypal 19th-century British plunderer of antiquities. Among the priceless relics of an entire culture to which Layard helped himself were the palace reliefs of lion and bull hunts that will form the centrepiece of the new exhibition. The display will also include some of the 30,000 cuneiform tablets from the famed library created by Ashurbanipal at Nineveh, also lifted by Layard.

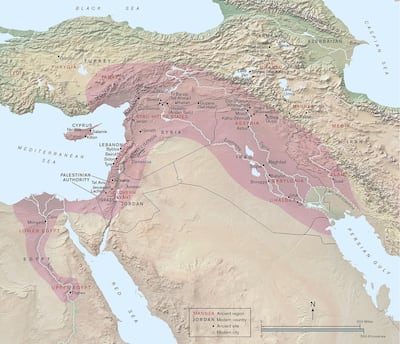

The museum’s “world-renowned collection of Assyrian treasures will be complemented by key loans from across the globe”, but not quite the entire globe. The items on display will include objects from Paris, Berlin, St Petersburg and the Vatican. But the fact that nothing in the show will have been sourced from any of the six modern-day countries, including Iraq, where the Assyrian empire existed, tells its own story.

It is true, as a spokesperson is keen to point out, that the British Museum does, from time to time, lend objects from its collection – and even entire exhibitions – to selected countries as "a vital part of [its] commitment to being a museum for the world". As part of its long-term consultative collaboration with Abu Dhabi and the Zayed National Museum, in 2011 and 2012, Manarat Al Saadiyat played host to two consecutive travelling shows – the Splendours of Mesopotamia, which included Assyrian objects, and Treasures of the World's Cultures. The touring exhibition, Age of Luxury, currently in Hong Kong, also features Assyrian pieces.

But lending and collaborating is not the same as returning. In August 1971, Iran asked the British government if it could borrow the Cyrus Cylinder from the British Museum as part of celebrations marking the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the Persian empire. The inscribed cylinder, bearing the words of what some historians have described as the world’s first declaration of human rights, was created during the reign of the Persian emperor Cyrus, and recorded his conquest of Babylon in 539BC.

The artefact, unearthed at modern-day Amran in Iraq by a disciple of Layard in 1879, had been on display in the British Museum ever since. Once-confidential documents, since released, show that the request divided the British establishment. It was initially rejected, on the imperious ground suggested by the country's foreign office that to loan the object would "merely arouse Iranian cupidity". At the same time, others argued that the cylinder should be returned permanently to Iran, to "improve the atmosphere of our relations".

It fell to Lord Trevelyan, then chair of the British Museum, to reject even a suggestion that the cylinder be loaned to Iran every third year. It would, he wrote to the Home Office, be "incredibly unlikely that the Iranians would ever return the tablet". But worse, the museum held "so many historic relics from foreign countries that … they would undoubtedly be flooded with similar requests".

___________________

Read more:

Assyrian sculpture claimed by Iraq sells for $31 million in New York

Ancient Assyrian sculpture up for sale at Christie’s – but should it ever have left Iraq?

British Museum's new gallery shows the influence of Islam in the Middle East and beyond

UAE funds rebuilding of Mosul’s Al Nuri Mosque and historic minaret

Restoring Mosul's lost treasures one byte at a time

___________________

In the end, the cylinder was lent, and duly returned. The loan was not repeated until 2010, when it went on show at the National Museum in Tehran and caused a sensation, demonstrating beyond doubt that there exists a hunger for first-hand experience of heritage in the lands where such historical artefacts originated.

In 2015, the British Museum, with the financial support of the its government, developed an Iraq Emergency Heritage Management Training Scheme, in response to the destruction wrought at some of the country's key archaeological sites by ISIS. Since then, it has evolved to provide training in modern archaeological techniques for a new generation of Iraqi archaeologists.

Perhaps it will be from this generation that the call will eventually come for the return of the treasures of Mesopotamia to Iraq, a country that is working hard to build its heritage-related tourism. If it does, the land that gave birth to modern civilisation will join the growing chorus of dissent around the world from nations who believe it is time for the West to turn its back on its imperial past – and to place the displaced treasures of the ancient world in crates for shipping home.

I am Ashurbanipal King of the World, King of Assyria is on display until February 24. For more information, visit www.britishmuseum.org