Ahmed Al Falahi cannot count the number of guests he has hosted in the past two weeks. Most of the time he can’t count the number of guests he has in a single day.

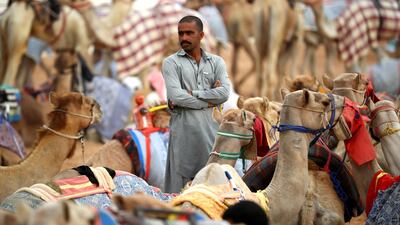

Thursday is the final day of this year’s Al Marmoom Heritage Festival in Dubai, the last tournament in the Gulf camel race winter circuit. When thousands of Omanis, Saudis and Kuwaitis showed up on Dubai’s doorstep for camel tournaments, Emirati camel owners like Mr Al Falahi open the doors to their ezba ranches to give them breakfast, lunch, dinner and a place to rest their head.

“That’s why the government do races, so that people can come together and sit together,” said Mr Al Falahi, 34, at his ezba – a cross between a ranch and a hobby farm - in Marmoom. “We feel happy when someone comes to us. These people are all our friends. When they see us here, they come.”

Just as the races are a way for the state to distribute millions in prizes and cash to camel owners, the winners are expected to pay it forward.

The ezba is a plot of land in the desert or mountain that has camel or goat pens, housing for caretakers and large indoor and outdoor majlis seating areas where owners gather at weekends.

The evolution of modern camel racing has spurred the rise of the super-ezba. Modest shacks of corrugated iron or breeze block have been replaced by palatial, multi-room buildings furnished with plush sofas, thick carpeting and chandeliers.

The super-ezba has a reputation proportionate to the generosity of its host and the fame of his camels. When traders from neighbouring Gulf states shows up at the track and asks where to gather, track locals can rattle out a long list of suggestions. Any newcomer can find instant friends and a meal.

Mr Al Falahi spent evenings this week with dozens of guests from Saudi Arabia, Oman and other Emirates. Some he knew, others were newcomers. All are welcome.

“This guy is from Riyadh, from Saudi Arabia and the other people from Oman,” said Mr Al Falahi, introducing his guests. “They know who owns the famous camels, and they go to his ezba.”

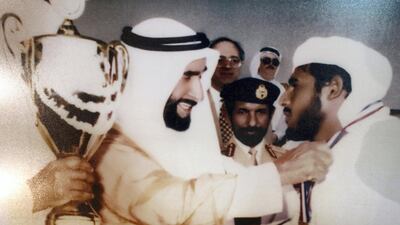

The reputation of the family ezba was cemented a generation ago with the victories of Shabla, a camel trained by Mr Al Falahi's father. The latest incarnation of the family ezba in Marmoom is a compound with a mosque, two indoor majlises, a kitchen, and worker’s quarters. It was a gift from Sheikh Hamdan bin Mohammed, the Crown Prince of Dubai and a patron of the camel racing industry.

To share his good fortune, Mr Al Falahi employs three full time cooks to prepare three meals a day. Ahead of the tournament he had friends bring a bulk order of halwa, a traditional rose-oil sweetmeat, from the Omani city of Niwza, 400km south of Dubai. Nizwa has a reputation for the best halwa in the Gulf and only the best halwa in the Gulf could be served to the Gulf’s best racers.

The majlis interior is testament to the family’s trackside prowess. Its walls are decorated with posters of distinguished race camels that have won swords and luxury 4x4s. Each montage had a photo of the camel either mid-stride or slathered in saffron post-race, the camel’s prize and its owner.

Prizes at this year’s Marmoom festival are worth Dh153 million and this has attracted hundreds of breeders and buyers.

The social contacts formed at the ezba are lucrative. Only half of the tournament takes place at the track. The rest happens at the ezba, over a post-race breakfast of khabees or after evening prayers when people gather to sip fresh camel's milk from small ceramic teacups.

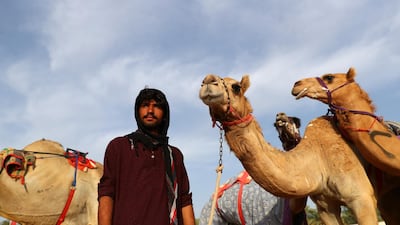

Among Mr Al Falahi’s guests were Omani camel traders from the southern deserts of Al Sharqiyah, like his friend Mana Mohammed.

“Of course he takes a percentage, you know,” said Mr Al Falahi. “It’s a skill, a job. His job.”

“It’s the stock market,” said Mr Mohammed, who is 26.

Mr Mohammed’s last sale to Mr Al Falahi was a camel worth Dh150,000.

It had yet to make a return.

Mr Mohammed shrugged. “Any trader must win and lose, am I right?”

He claimed to have made the long journey to the Emirates from south east Oman with no expectation of personal gain. “I came for love of the camels,” he said.

Mr Al Falahi’s younger brother, Theyab, shook his head. “Brokers came here and they make Dh200,000 in a few days.”

The last of Mr Al Falahi’s guests will disappear this weekend.

“It will be boring,” sighed Mr Al Falahi. “So, so, boring.”